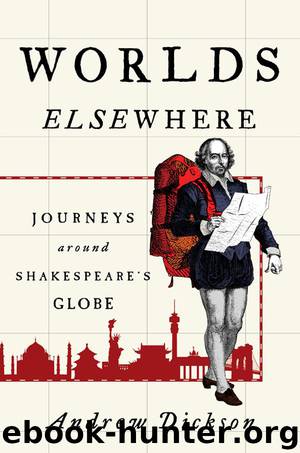

0805097341 (N) by Andrew Dickson

Author:Andrew Dickson

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Publisher: Henry Holt and Co.

Published: 2016-02-19T22:00:00+00:00

It was after 9 p.m. by the time I got back to the hotel: early by Indian standards, but I couldn’t face finding a restaurant outside. There was a café of sorts in the lobby. I dumped my bag on the closest table and, not bothering to glance at the menu, ordered the largest beer they had and a portion of daal and rice. Aside from a fleet of waiters checking their phones, there was just one other diner, a porcine businessman in a striped shirt pecking at his laptop.

It is a hazard of travelling alone that one’s emotions become Himalayan extremes: the highs exultant, the lows desperate. But I reasoned that I had some cause to feel despair. Granted, I had managed to see Hamlet, the oldest surviving Shakespeare film in India – but that a movie from the mid-1950s was considered uniquely antique had come as a shock.

By the evanescent standards of my usual trade, theatre, film had always seemed to me almost alarmingly permanent: all you needed to do was hang on to the stuff. But it appeared almost no one, bar P. K. Nair and a few others, wanted to bother. There he was, in his gloomy little room, while films rotted into nothing a few hundred yards away. The thought was incalculably depressing.

No doubt films were being preserved, and the chances of a few lost reels popping up in someone’s attic were really rather high. Digitisation made it harder to delete things. India was at the forefront of technology: the wi-fi on the train to Pune had been faster than it was in my London flat. But in its scrambled hurry to modernise, the country seemed sometimes to regard its own past as an impediment. I remembered a line I’d read somewhere. ‘India has a rich past, but a poor history.’ It was a cliché, but hard to deny.

I thought back to C. J. Sisson’s essay, the point at which I had begun my journey. One of the things he most admired about Parsi theatre was how it resembled Elizabethan drama: its exuberant commercialism, its restless creativity, its bumptious optimism. In Mumbai, he had written, ‘[Shakespeare’s] plays … are still alive and in the process of becoming new things, being ever born again.’ That was surely true, and true about Bollywood too – but what was also true was that this hunger for invention turned the industry into an inattentive custodian of the old. If you could simply remake a film, why bother to save the original? It was just last year’s movie, just cluttering up someone’s floor.

But then, as I’d discovered at the Folger library, the Jacobethans hadn’t been much good at preservation, either. If the First Folio hadn’t been published in 1623, eighteen of Shakespeare’s plays would probably never have survived. The overwhelming majority of Renaissance playscripts are in exactly the same condition as India’s silent cinema: long since lost in action.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

International Integration of the Brazilian Economy by Elias C. Grivoyannis(57323)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10907)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(7039)

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(6633)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(6190)

Pioneering Portfolio Management by David F. Swensen(5606)

Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert T. Kiyosaki(5149)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4824)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(4736)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3782)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3569)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3460)

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff(3422)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(3284)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3264)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(3180)

The Dhandho Investor by Mohnish Pabrai(3168)

The Wisdom of Finance by Mihir Desai(3078)

Blockchain Basics by Daniel Drescher(2891)