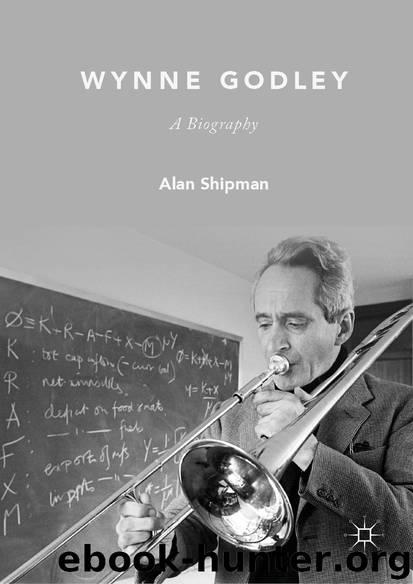

Wynne Godley by Alan Shipman

Author:Alan Shipman

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9783030122898

Publisher: Springer International Publishing

Misleading Defences

By floating the pound in 1972 and dismantling the remaining capital-account restrictions and deregulating the financial sector after 1979, the Conservatives believed they could remove any balance of payments constraint , and their Chancellors began publicly downplaying the importance of large external deficits. These would either be corrected by letting the pound depreciate against trade-partner currencies or financed by attracting capital inflows. Depreciation was likely to be the appropriate policy if the economy were below full employment , since it would deflect demand from imports onto domestic production and was consistent with setting interest rates below those of competitor economies. Financing might be an alternative if the economy had reached full employment, since the higher interest rate (than competitors economies’) required to tame inflationary pressures would also help to attract foreign capital inflows.

So responses to the ‘Cambridge’ diagnosis of Britain’s ills divided between denying that deindustrialisation was a problem, and ascribing it to other structural factors for which Godley’s preferred policies could be criticised as cause rather than cure. The ‘no problem’ approach denied that there was anything special about manufacturing, and saw its demise as a progressive, market-determined structural change. Contrary to the CEPG assertion, tradable services could be produced independently of manufacturing activity, fully replace its contribution to exports, and generate the productivity growth that would allow real incomes to keep rising. If the UK was unique in losing manufacturing industry, rather than just seeing its capacity level off and more of its processes outsourced overseas, this was merely because the UK had an unusually strong comparative advantage in financial, business and other services, which stood it in good stead for the longer-term future when emerging economies achieved their own low-cost manufacturing base. There were shades of this argument even when industrialists were protesting the early-1980s squeeze due to oil exports and rising exchange rates. The strong pound meant a shrinkage of manufacturing net exports was ‘natural’, to be reversed if and when the pound came down again. If closed factories and mines were not easily reopened then, because they’d been dismantled and not just mothballed.

Economists who accepted ‘negative’ deindustrialisation as a reality had plentiful alternative explanations, exonerating the exchange rate. Disruptive trade unions, pushing wages too high while resisting productivity-raising investment and more flexible hiring, were a popular target. So too were excessive regulation and the UK welfare state, accused of further distorting the labour market through inflated benefit levels that really Greater attention was paid to the Oxford-based economists Robert Bacon and Walter Eltis (1976, 1978), who argued that UK industry had been crowded out by the growth of the public sector, which they accused of diverting resources from a productive private sector into state agencies and enterprises that offered no marketable or exportable output. Pointing out that the UK had transferred a far higher proportion of its workforce from private industry to public services (especially education and health care) than West Germany or Italy, Bacon and Eltis (1978: 16–17) calculated that net investment in ‘non-market’ sectors had risen to 22.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16623)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11489)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(7788)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(5771)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5036)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4824)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(4789)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4447)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(4417)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(4415)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4398)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4342)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4076)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4032)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4012)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(3881)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(3872)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3782)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3730)