Working Women, Entrepreneurs, and the Mexican Revolution by Heather Fowler-Salamini

Author:Heather Fowler-Salamini [Fowler-Salamini, Heather]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 978-1-4962-1164-4

Publisher: University of Nebraska Press

Published: 2018-07-14T16:00:00+00:00

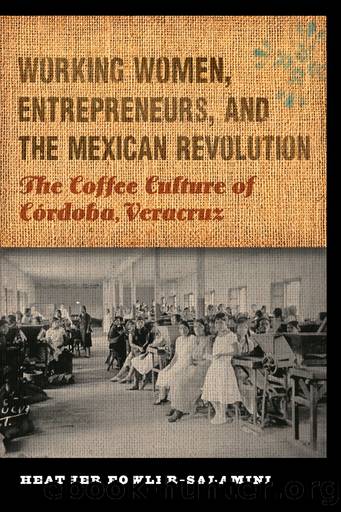

9. Military band of the SOECC, 1946. Photograph by California. Courtesy of Brígida Siriaco García.

Like other union bands, the SOECC band served a legitimizing function for the labor movement. Its leaders sought to use its performances to foster union loyalty and solidarity and to present to the community at large a socially respectable and disciplined organization playing in public venues. The band’s primary purpose was to provide entertainment at SOECC-sponsored biannual dinners and dances. Each June and December, it played for the installation of the new executive committee. Since the union had been a founding member of the CSOCO, the band performed at almost all its celebrations. The installation of a new Santa Rosa executive committee of the textile union or León’s birthday celebrations always found the SOECC band performing. When the SOECC joined the Confederación Regional de Obreros y Campesinos (CROC, Regional Confederation of Workers and Peasants), its band became a fixture at CROC celebrations throughout the state. It even played in Poza Rica for the oil workers’ union, after it affiliated with the CROC. The petroleum workers had earlier organized a mixed-gender band for a few years, but it later returned to an all-male one.60

The SOECC band served an overtly political function as well, when it performed on national holidays for municipal and state authorities of the renamed official party, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI, Institutionalized Revolutionary Party). Since the Porfiriato, municipal bands had become permanent fixtures at patriotic festivals, and now union bands joined them in the postrevolutionary era. In agreeing to participate in official commemorations of the Mexican Revolution, the SOECC band, like other union bands, was inserting itself into the body politic.

Córdoba’s PRI-controlled municipal government regularly invited the SOECC band to participate along with the municipal band in the parades for February 24 (Flag Day), March 21 (Benito Juárez’s birthday), May 1 (Labor Day), September 15 and 16 (Independence Day), and November 20 (Revolution Day). The banda de guerra was aiding the official party by instilling Mexican nationalist values. Their participation in the May 1 celebrations had another important objective and an interesting gendered dimension. “There is no public act that better dramatizes the power of caciques, nor any ritual that better reaffirms union hierarchy, than the May 1st (Labour Day) celebrations.”61 In these marches, the SOECC and its band always went in front of all the other regional unions. The male street-vendor and the sugarcane-worker bands with their unions followed them. The regional federation most probably decided to give the SOECC greater prominence because it was the largest union, but some interviewees claimed it was because they were women. The sight of the band, honor guard, military auxiliary, and its 1,500 members filling several downtown city blocks on May 1 or November 20 could not but have impressed the townspeople and brought pride to the participants themselves (see photograph 10). In addition to marching in holiday parades, the band had to play for the raising and lowering of the flag at six o’clock in the morning and in the evening.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Arms Control | Diplomacy |

| Security | Trades & Tariffs |

| Treaties | African |

| Asian | Australian & Oceanian |

| Canadian | Caribbean & Latin American |

| European | Middle Eastern |

| Russian & Former Soviet Union |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16623)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11489)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(7788)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(5771)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5036)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4824)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(4789)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4447)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(4417)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(4415)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4398)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4342)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4077)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4032)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4012)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(3881)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(3872)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3782)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3731)