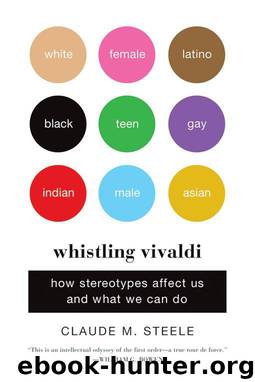

Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do (Issues of Our Time) by Steele Claude M

Author:Steele, Claude M. [Steele, Claude M.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Norton

Published: 2011-04-04T00:00:00+00:00

2.

It’s a good thing Steve Spencer, Josh Aronson, and I knew this when we turned to the problem of how identity threat has its effects, because we ran smack into this limitation of human functioning, people’s limited access to their feelings and to the causes of their feelings. We had always assumed that identity threat made people anxious and that it was the anxiety it caused that directly impaired performance. Anxiety, we thought, was the performance-damaging handmaiden of threat. It seemed obvious.

In our very first experiments, though, when Steve and I asked women taking a difficult math test under stereotype threat how anxious they felt, they reported no more anxiety than women taking the test under no stereotype threat (that is, when they understood the test to show no gender differences). The women performed worse under stereotype threat—the finding that launched this research—but they didn’t report being any more anxious. We were puzzled.

Later on, Josh and I got further puzzling results. As the data came in showing the effects of stereotype threat on black students’ verbal test performance, our feet on the desk, we wondered whether the threat was making them anxious and whether that was why they underperformed. Josh started interviewing our research participants. He found nothing: those under stereotype threat reported no more anxiety than those not under stereotype threat. The stereotype threat participants seemed calm, resolved. They said the test was difficult, but that they were determined to bear down and do well. They believed that their effort would see them through. They said these things even as we could see from their test booklets that they hadn’t done well at all.

So it was a good thing that we knew how limited people are in reporting on internal states like anxiety. It helped us not be convinced by the lack of evidence showing anxiety reactions to stereotype threat. And it helped us take more seriously some of the counterevidence. Remember that people under stereotype threat completed more word fragments with words related to the stereo type. This suggests they were anxious about confirming the stereo type or being seen as confirming it. Black students under stereo type threat also did other things that suggested they were anxious about being stereotyped. They reported less preference for things associated with blacks—jazz, hip-hop, and basketball—and more preference for things associated with whites—classical music, tennis, and swimming. They offered more excuses in advance of their performance, like saying they got little sleep the night before. Such tendencies suggested they were anxious. But these same participants wouldn’t directly tell us they were anxious. Perhaps they didn’t want to admit to it. Or perhaps, like the men who met the attractive interviewer after crossing the Capilano Bridge, they didn’t know they were anxious.

To know how central anxiety was to stereotype threat effects, we needed a better measure of anxiety, one that didn’t depend on what people knew about themselves.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7692)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5431)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5408)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4565)

The Sports Rules Book by Human Kinetics(4379)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(4375)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4242)

Captivate by Vanessa Van Edwards(3838)

Mummy Knew by Lisa James(3686)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3536)

The Worm at the Core by Sheldon Solomon(3486)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3460)

The 48 laws of power by Robert Greene & Joost Elffers(3245)

Suicide: A Study in Sociology by Emile Durkheim(3018)

The Slow Fix: Solve Problems, Work Smarter, and Live Better In a World Addicted to Speed by Carl Honore(3007)

The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell(2914)

Humans of New York by Brandon Stanton(2868)

Handbook of Forensic Sociology and Psychology by Stephen J. Morewitz & Mark L. Goldstein(2692)

The Happy Hooker by Xaviera Hollander(2686)