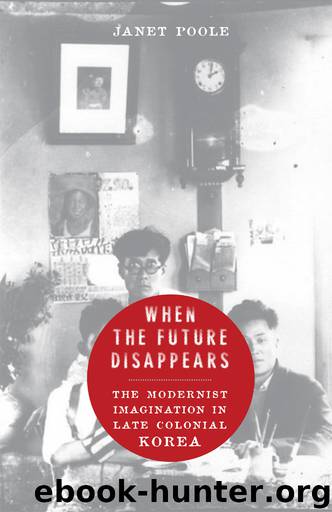

When the Future Disappears by Poole Janet

Author:Poole, Janet [Poole, Janet]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: LIT008000, LITERARY CRITICISM/Asian/General, HIS023000, HISTORY/Asia/Korea

Publisher: Perseus Books, LLC

Published: 2014-03-11T16:00:00+00:00

The tragic death of a child opens Korean Literature in the Age of Transition (Tenkanki no Chōsen bungaku), a collection of essays by the eminent literary critic Ch’oe Chaesŏ (1908–64) which was published in 1943. Moving as it is, the dedication to Ch’oe’s recently deceased son cannot help but also stun the reader of today as it compresses into just a few lines the narrative of death and rebirth that lies at the heart of the rhetoric of imperialization.1 As the Government General was urging Koreans to die on the battlefield for the Japanese emperor in order to become truly Japanese, Ch’oe’s words offer a variation on this tale of rebirth and an intensely personal witness to the powerful attraction and comfort offered by the possibility of becoming Japanese. How could a literary journal that supported total mobilization salve the dreadful loss of a child? How could a campaign to “imperialize” the population of Korea substitute for the promise of a future lost with the unexpected death of Kang?

Kokumin bungaku was the name both of a journal and a literary project, meaning literally the “literature of the national people.” In 1941 the Government General had closed down the two major journals that had supported literary life in Korea from the late 1930s and past the forced closure of the vernacular press in 1940: Munjang, whose antiquarian focus had led an excavation into Korea’s literary past and played a major role in the christening of the classics, and Inmun p’yŏngnon, whose lively debates on literature and daily life were interspersed with articles on foreign literary trends written by its contributors, many of whom were scholars of various European literatures. The reason given for the closure was the need to ration paper, but all knew that the police department, which gave the order, was really aiming at reform of intellectual and artistic life in Korea, as Ch’oe Chaesŏ, then editor of Inmun p’yŏngnon, later acknowledged.2 In October 1941 the first issue of a new journal supported by the Government General appeared; its title was Kokumin bungaku, and its editor was Ch’oe Chaesŏ. At first the editorial plan was to publish eight issues per year in Korean and four in Japanese, but soon, with the escalation toward total mobilization in 1942, Kokumin bungaku became an entirely Japanese-language journal, containing essays, fiction, and poetry written by Korean and Japanese writers and thinkers. Its editorial mandate was to actively support state policy, to raise national awareness (kokumin ishiki) among Korea’s cultural figures, and to promote the creation of a “new culture” that “merged” those of Korea and Japan.3 In other words, Ch’oe—a leading scholar of British modernism and supporter of Korea’s own avant-garde writers—had become a figurehead for the project of inaugurating a literature on the Korean peninsula that affirmed itself as part of the imperial nation and supported its causes, which were invested deeply, and struggling, in war. What had brought the literary critic, who had been so fundamental to the institution of a

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Arms Control | Diplomacy |

| Security | Trades & Tariffs |

| Treaties | African |

| Asian | Australian & Oceanian |

| Canadian | Caribbean & Latin American |

| European | Middle Eastern |

| Russian & Former Soviet Union |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19002)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12177)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8874)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6857)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6248)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5767)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5717)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5482)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5409)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5200)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5130)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5065)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4900)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4761)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4727)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4685)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4489)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4474)