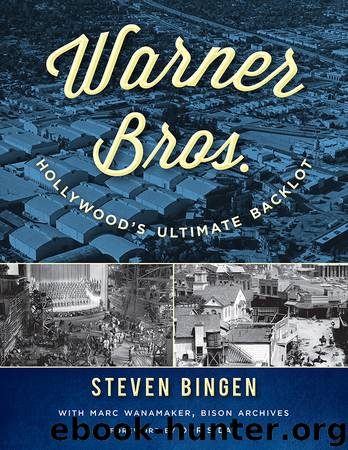

Warner Bros. by Steven Bingen

Author:Steven Bingen

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Taylor Trade Publishing

Published: 2014-08-02T16:00:00+00:00

But at the end of the day, the biggest mystery inherent in a study of the Warner Bros. backlot involves not policy or logistics, but rather those intangibles that the backlot evokes, both on the screen and off. I’ll always remember being told once by some old-timer about how, when Humphrey Bogart would have too much to drink, he would occasionally steal a studio bicycle and then proceed to peddle drunkenly across the backlot, shouting obscenities about his boss, Jack Warner, and then listening to those oaths dance and echo across the façades.

You know, sometimes when I’m alone out there and the sun is setting, gathering black-and-white shadows across those same façades, I feel like I can hear Bogie still.

1. Brownstone Street

One of the staples of any studio’s backlot, then as today, is a Brownstone Street. The reasoning for this is that there are no authentic brownstones in California. Even today, there are Brownstone Streets in most modern studios in Los Angeles. The oldest original specimen is here at Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.’ Brownstone Street seems to have grown out of a First National Picture called Lady Be Good (1928). The original street ran east from the Commissary and, then as now, consisted of a series of five staircases and numerous doorways and windows decorating a row of three-story brick homes, all supposedly based on a part of Manhattan’s Lexington Avenue. The opposite (northern) side of the street, surprisingly, was never more brownstones, but rather a row of east coast–style small business and office-based façades, which never really matched or complemented the buildings they faced.

Through the 1930s, the street survived and was expanded upon. As the adjacent New York Street grew around the district, a large façade with rounded doorways appeared at the eastern end of the street, allowing for a much wider variety of camera angles when photographing Brownstone Street from the west. In the mid-1930s, interiors were added in back of some of the doorways, and a storage hanger for carbon arc-lighting equipment was installed on the building’s backside. A complete stairway with landings was also constructed inside one of the front doorways and was used extensively for a shootout between Bogart and Edward G. Robinson in Bullets or Ballots (1936).

Gangster films such as this contributed to the street’s white-hot résumé during this period. Doorway to Hell (1930) marked Cagney’s first attempt at this genre. Little Caesar (1931) was Robinson’s. Both of these pictures utilized the set. Bogart’s The Maltese Falcon (1941) placed the exterior of Sam Spade’s apartment at the end of the street. But The Big Sleep (1946) brazenly used the same façade as the “Holbart Arms” hotel. Years later, in The Young Philadelphians (1959), Paul Newman is represented as living in the very same building. This doubling and tripling up of who-slept-where-when extends to all the structures on the street. A doorway on the other end of the block has been passed off as being the home both of television’s Murphy Brown and of Wonder Woman!

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5534)

The Sports Rules Book by Human Kinetics(4367)

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff(4267)

ACT Math For Dummies by Zegarelli Mark(4034)

Unlabel: Selling You Without Selling Out by Marc Ecko(3639)

Blood, Sweat, and Pixels by Jason Schreier(3596)

Hidden Persuasion: 33 psychological influence techniques in advertising by Marc Andrews & Matthijs van Leeuwen & Rick van Baaren(3536)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(3420)

Bad Pharma by Ben Goldacre(3413)

Urban Outlaw by Magnus Walker(3380)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(3207)

Kitchen confidential by Anthony Bourdain(3071)

Brotopia by Emily Chang(3040)

Slugfest by Reed Tucker(2988)

The Content Trap by Bharat Anand(2910)

The Airbnb Story by Leigh Gallagher(2834)

Coffee for One by KJ Fallon(2615)

Smuggler's Cove: Exotic Cocktails, Rum, and the Cult of Tiki by Martin Cate & Rebecca Cate(2508)

Beer is proof God loves us by Charles W. Bamforth(2434)