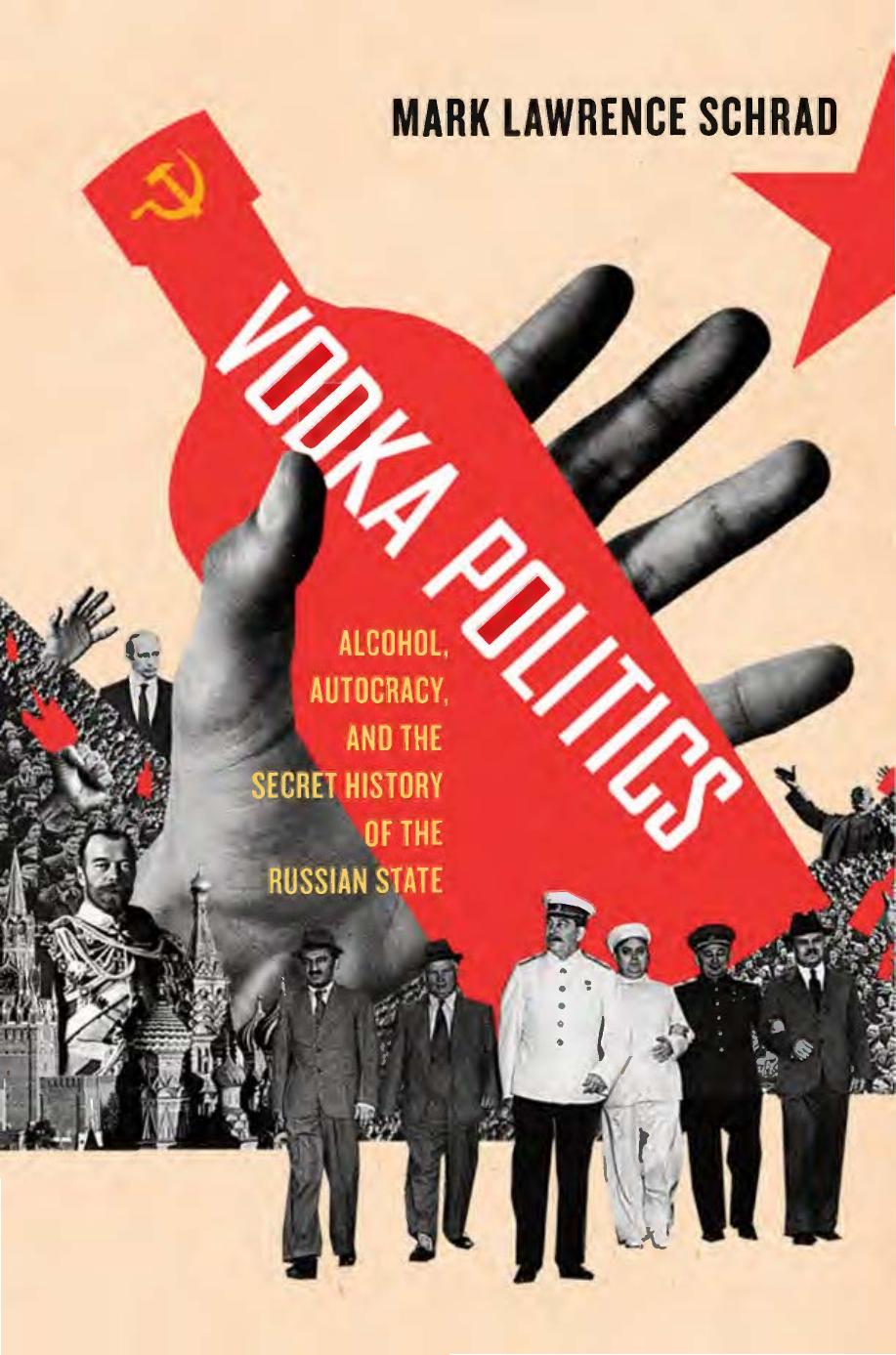

Vodka Politics by Schrad Mark Lawrence

Author:Schrad, Mark Lawrence

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Oxford University Press, USA

Published: 2014-04-07T16:00:00+00:00

For centuries, alcohol revenues were the central economic pillar of the Russian autocratic state, so it is no surprise that the most vocal opposition came from those most aware of the economic consequences. When the deputy director of the state economic planning agency Gosplan warned that there was no conceivable way to cover the gap of five billion rubles that would result from the campaign, Gorbachev gave him a dressing down: “You want to build communism on vodka?”63

After refusing to sign off on the plan three different times, the Gosplan director was threatened with expulsion from the Communist Party. He was joined in his dissent by Vasily Garbuzov. Promoted to minister of finance under Khrushchev in 1960, Garbuzov oversaw and promoted vodka as “Commodity Number One” for the Soviet treasury over the following twenty-five years. As architect of late-Soviet vodka politics he understood more than anyone the economic implications of the proposed measures, so it was Garbuzov whom Gorbachev first summoned to discuss the issue. His protests notwithstanding, Garbuzov also refused to sign the anti-alcohol resolution. Within weeks the elderly finance minister followed Gorbachev’s rival Romanov into forced retirement.64

Gorbachev’s threat of dismissal sufficiently intimidated those on-the-fence Politburo members, including Eduard Shevardnadze—who soon replaced Gromyko as Soviet foreign minister and later became president of an independent Georgia. Reflecting the moderate traditions of the predominantly wine-drinking Caucasus, Shevardnadze says he was “horrified” over the anti-alcohol plans but admitted that he voted for them, “although inwardly I disagreed.”65

Others were not so easily cowed, including Heydar Aliyev, who later became president of post-Soviet Azerbaijan, next door to Shevardnadze’s Georgia. The Politburo’s only Muslim member, the cultured Aliyev drank only the cognac of his native Caucasus and preferred the company of composers, actors, and artists over the usual “alcoholics, foul-mouthed swearers and womanizers” of the Kremlin.66 Yet the powerful deputy prime minister embodied the corruption and nepotism of the old Brezhnev era—transforming Soviet Azerbaijan into a personal fiefdom of oil, cotton, and caviar.

In protecting his own interests, Aliyev also refused to sign the anti-alcohol resolution. He continued even after the campaign was in full swing: protesting—ultimately in vain—the closure of a champagne factory he recently had set up in Azerbaijan with high-end equipment imported from West Germany. This continued opposition brought him toe to toe with the drys: Gorbachev, Ligachev, and Solomentsev. When he later protested the closing of breweries on the grounds that beer was “not really alcohol,” Solomentsev threatened to produce a report “proving that people got more drunk from beer than vodka.” When he argued that drunkenness was not a big problem in traditionally Muslim, wine-producing Azerbaijan and that ninety-five percent of their wine was exported to other regions, “Ligachev went to Azerbaijan and carpeted the republic’s leaders, accusing them of poisoning the rest of Russia with their drink.”67

Aliyev’s opposition to the anti-alcohol campaign only hardened the reformers’ view that he exemplified the nepotism, privilege, and corruption of the Brezhnev era. In 1987 “Gorbachev unleashed a full-blown, Stalin-style denunciation of Aliyev,” dismissing him for corruption and cronyism.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Arms Control | Diplomacy |

| Security | Trades & Tariffs |

| Treaties | African |

| Asian | Australian & Oceanian |

| Canadian | Caribbean & Latin American |

| European | Middle Eastern |

| Russian & Former Soviet Union |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16627)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11489)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(7788)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(5775)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5038)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4824)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(4789)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4449)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(4420)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(4417)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4399)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4343)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4079)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4033)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4012)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(3883)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(3872)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3783)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3732)