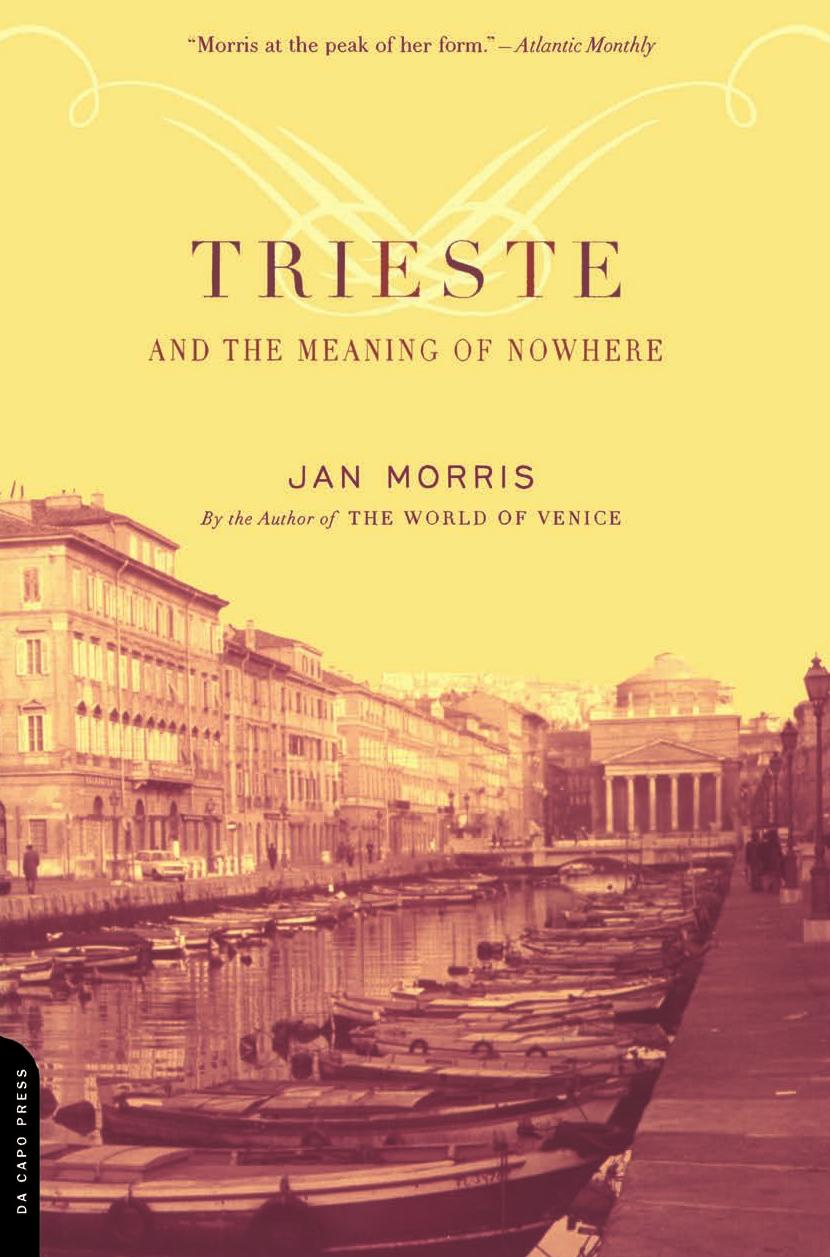

Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere by Jan Morris

Author:Jan Morris [JAN MORRIS]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Da Capo Press

Published: 2012-01-25T05:00:00+00:00

NINE

Borgello, Kofric, Slokovich and Blotz

“We are the eastern limit of Latinity and the southern extremity of Germanness,” a Mayor of Trieste told me long ago. He might well have said that they were the western extremity of Slavdom, too, but perhaps that would then have been politically incorrect. Any Mayor of Trieste has to think ethnically, because this city is not simply a junction of political frontiers, it is an old fusion of bloodstocks. Today its population is overwhelmingly Italian, but I am told that when its football team goes to play in the Italian south, its players are still cat-called as Slavs or Balkans. Trieste is of Italy, but not altogether of it, and nothing could be much less like the effusive, song-singing, tricky, sun-burnt, fast-driving and volatile Italian of the world’s imagination than your average Triestino.

A look at passing faces will confirm that. In the countryside around Trieste live many Slovenes of purest blood. Within the city are thousands of utter Italians. But for generations this place was a melting-pot of races and types, and its faces show it still. There is the straight northern Italian face, firm but a little dreamy; there is the Germanic Austrian face; there are faces with high cheek-bones and slightly slanting eyes that speak of Hungary; there are fair-haired, blue-eyed Balkan faces. Very few of them are absolute, though. They are all mixed up, a tinge here, an echo there. The hybrid human is the norm in this city. Mayor lily’s paternal grandfather was from Transylvania; his grandmother was half-Irish and half-Austrian. Maestro Banfield-Tripcovich of the tugs and the Opera Verdi was the son of an Austrian of Irish descent, by a Slovene countess. Temperaments merge here too; Slataper the poet said of himself that blended in his character was Slavic nostalgia, German certainty and an Italian instinct for harmony.

Any list of Trieste names, in almost any context, is bewil-deringly multi-ethnic. Take for instance a war memorial slab beneath the walls of the citadel, up on San Giusto hill. The most summary run of your eye down its roster will show you a Borgello, a Slocovich, a Brunner, a Sylvestro, a Zottin and a Blotz. The orchestra that played Smareglia’s Nozze Istriani, last time I was at the opera, included violinists named Ivevic and Leszczynski, a cellist called Iztpk Kodric, Neri Noferini a horn player and an oboist named Giuseppi Mis Cipolat. Down the generations many Triestini have had their names ethnically adjusted, too, as a sort of first step towards genetic reconstruction. A Topico might become a Topić, a Kogut turn into a Cogetti. It depended upon the political circumstances of the day, and upon economic opportunity. Sometimes a change was made by order of the State, sometimes it was made as an explicitly personal statement. Italo Svevo, for instance, was born Ettore Schmitz: his nom de plume told everyone that he was Italian by loyalty but was born in Swabia, and combined in himself elements of both their cultures.

In all this Trieste was a microcosm of the empire.

Download

Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere by Jan Morris.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

How to Read Water: Clues and Patterns from Puddles to the Sea (Natural Navigation) by Tristan Gooley(2849)

Full Circle by Michael Palin(2764)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(2695)

How to Read Nature by Tristan Gooley(2657)

The Lost Art of Reading Nature's Signs by Tristan Gooley(2282)

In Patagonia by Bruce Chatwin(2263)

Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes by Daniel L. Everett(2213)

City of Djinns: a year in Delhi by William Dalrymple(2131)

L'Appart by David Lebovitz(2113)

The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin(2109)

Venice by Jan Morris(2048)

The Big Twitch by Sean Dooley(2041)

A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini(1983)

Tokyo Geek's Guide: Manga, Anime, Gaming, Cosplay, Toys, Idols & More - The Ultimate Guide to Japan's Otaku Culture by Simone Gianni(1943)

A TIME OF GIFTS by Patrick Leigh Fermor(1844)

Come, Tell Me How You Live by Mallowan Agatha Christie(1764)

The Queen of Nothing by Holly Black(1749)

INTO THE WILD by Jon Krakauer(1719)

Iranian Rappers And Persian Porn by Maslin Jamie(1706)