Tonal Structures in Early Music by Judd Cristle Collins

Author:Judd, Cristle Collins.

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781135704698

Publisher: Taylor & Francis (CAM)

“NAMING”

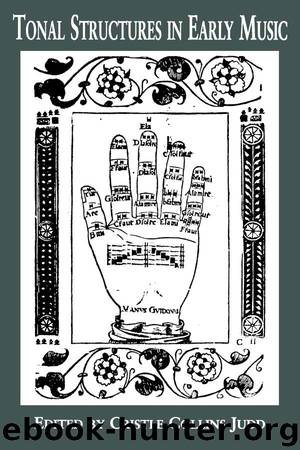

“Naming,” Bathe’s title for the first chapter of his primer, is the most fundamental and basic aspect of any theoretical system. English theorists resemble their counterparts on the continent (particularly Italy and Germany) in presenting the tonal system as the traditional gamut: a combination of the first seven letters of the alphabet (differentiated by octave through the use of capital, lowercase or double lowercase letters—from T to ee) and six hexachord syllables (ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la). They invariably use both littera and vox (for example, C sol fa ut) to refer to pitches in the texts of their treatises. Beneath this apparent similarity, however, lie striking differences in solmization and in pitch collections as defined by the presence or absence of one or more flats at the beginning of each staff—what we now call key signatures (Morley refers to them as “flat cliffes”).40

On the continent, writers generally explain that the gamut is a “universal” scale, built from all three hexachords and thus containing both Bfa () and B mi (). They divide the universal scale into two “particular” scales. The scale with no key signature, based on the C and G hexachords, is usually referred to as cantus durus or scala duralis. The one with a B signature, based on the C and F hexachords, is called cantus mollis or scala mollaris. Theorists sometimes recognize a third scale, with two flats, called cantus fictus, but its status is clearly inferior to the two main scales, cantus durus and cantus mollis.41 Note that “scale” in this sense means the collection of pitches defined by the hexachords and by the “key” signature.42

In contrast, many of the English writers routinely set forth three scales, usu-ally as the by-product of their rules for teaching students how to solmize. (See table 2a.) The rules for—and indeed the practice of—solmization differ somewhat from theorist to theorist, but the underlying concept of scale is remarkably similar. In contrast to continental practices, which give rules for mutating between hexachords (for example, notes are sung differently depending on whether the line is ascending or descending), in England the key signature usually determines the solmization, and in fact affixes particular syllables to particular pitches.43 The decision about how many syllables to use—only four, usually four but with occasional additions of a fifth and sixth syllable, six, or seven—occurs within the context of the near-universal adoption of a system employing three scales (no flat, one flat, two flats), in practice if not always in theory.

To see in greater detail how the English theoretical system presents the concepts associated with naming, we can begin with the earliest and in many ways clearest of the writers, William Bathe. As we shall see, his ideas—or at least the ideas he expresses—resonate during the entire period.44

Bathe sets forth the tonal system (“the Scale of Musick, which is called Gamut”) with its “letters and sillables” at the beginning of his treatise (fig. I).45 The beginner must “know, wherein every key standeth, whether in rule or in space: and how many Cliefes, how many Notes is contayned in every Key.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Ancient & Classical | Arthurian Romance |

| Beat Generation | Feminist |

| Gothic & Romantic | LGBT |

| Medieval | Modern |

| Modernism | Postmodernism |

| Renaissance | Shakespeare |

| Surrealism | Victorian |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11035)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(6838)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(5873)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(4719)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(4567)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4206)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(3982)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(3968)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3791)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(3705)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(3663)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(3578)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(3509)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(3430)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(3358)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3304)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3222)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3212)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3207)