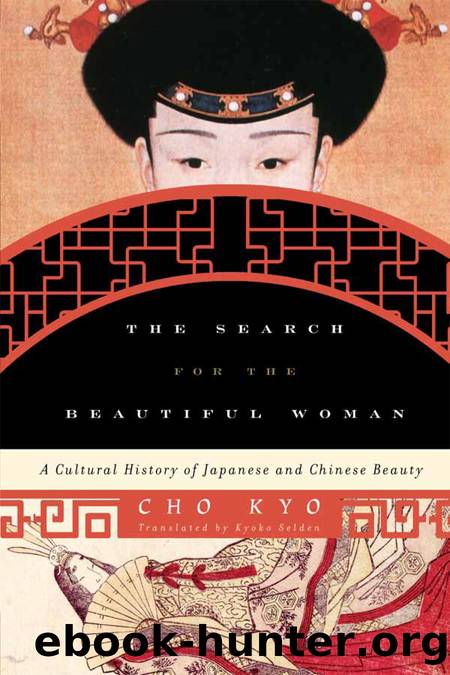

The Search for the Beautiful Woman by Cho Kyo

Author:Cho Kyo

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781442218956

Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

This is a well-known description of an ugly face.

However, even if we suppose that the view is derived from The Tale of Ochikubo, the question remains unresolved. Murasaki Shikibu bases herself upon the line, “The lotuses of Grand Inchor Pool, the willows by the Night-Is-Young Palace,”20 when she refers to Yang Guifei (Japanese Yōkihi) in The Tale of Genji: “A superb artist had done the paintings of Yōkihi, but the brush can convey only so much, and her picture lacked the breath of life. The face, so like the lotuses in the Taieki Lake or the willows by the Miō Palace. . . .”21 Judging from this, she knew well “The Song of Lasting Regret.” If so, she must have been aware of the line, “Whose snow-white skin and flower-like features appeared to resemble hers,”22 and the rhetoric of “snow-white skin.” However, we find in The Tale of Genji no rhetoric that likens the whiteness of the skin to the snow and presents it as beautiful. On the contrary, the tale carries on the aesthetic sense of The Tale of Ochikubo, which regards “the skin white as snow” as ugly.

Why was white skin ugly?

No Associative Relations Yet

There is a view that, against expectations, overly white skin can appear ugly.23 However, once the aesthetic sense of viewing white skin as beautiful establishes itself, being too white never should be problematic. The reason is that, if the concept that white skin means beauty becomes set, it creates a connotation that simply equates “white” with beauty. Then, white skin itself comes to be never viewed as ugly. In fact, we find no example in descriptions of countenances in Chinese literature in which white skin is portrayed as ugly.

When a woman looks white because of illness, lack of health, or excessive bleeding, the word white is not applied to her. In such cases, the expressions used are “sickly complexioned,” “pale,” “blanched,” “drained of color,” and so forth. Even today, when wheat-colored skin is regarded as beautiful in Japan, there are hardly any examples of character description in which “white skin” is presented as ugly.

Some may suspect that his white skin was ugly because Hyōbu no Shō was male. But there is hardly any possibility of that. The reason is that, once white skin came to be highly evaluated, it was considered attractive not only with women but also with men. We find supporting evidence in an episode from year 890 in “The Construction of the Outer Palace; Also the Sacred Hall” in chapter 12 of The Chronicle of the Great Peace (Taiheiki, fourteenth century; the first twelve of the forty chapters are known as The Taiheiki: A Chronicle of Medieval Japan in Helen McCullough’s translation):

So he thought, and put a bow with practice arrows in front of the Kan minister of state, saying, “Since it is the beginning of spring, amuse yourself awhile.”

The Kan minister of state did not draw back, but joined himself to a side. He bared his snowy skin to the waist, raised up and pulled down, steadied the bow for a while, and let go an arrow.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Fine Print (Dreamland Billionaires Book 1) by Lauren Asher(2550)

Fury of Magnus by Graham McNeill(2444)

The Last House on Needless Street by Catriona Ward(2387)

The Rose Code by Kate Quinn(2195)

A Little Life: A Novel by Hanya Yanagihara(2121)

The God of the Woods by Liz Moore(1921)

Malibu Rising by Taylor Jenkins Reid(1914)

Luster by Raven Leilani(1898)

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi(1853)

Moonflower Murders by Anthony Horowitz(1842)

The Lost Book of the White (The Eldest Curses) by Cassandra Clare & Wesley Chu(1688)

This Changes Everything by Unknown(1500)

The Midwife Murders by James Patterson & Richard Dilallo(1484)

The New Wilderness by Diane Cook(1439)

The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante(1430)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1419)

Written in the Stars by Alexandria Bellefleur(1400)

Ambition and Desire: The Dangerous Life of Josephine Bonaparte by Kate Williams(1385)

The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante;(1308)