The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture by Susan Stewart

Author:Susan Stewart

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Tags: LIT000000 Literary Criticism / General

Publisher: University of Chicago Press

Published: 2020-01-05T16:00:00+00:00

Fantasies

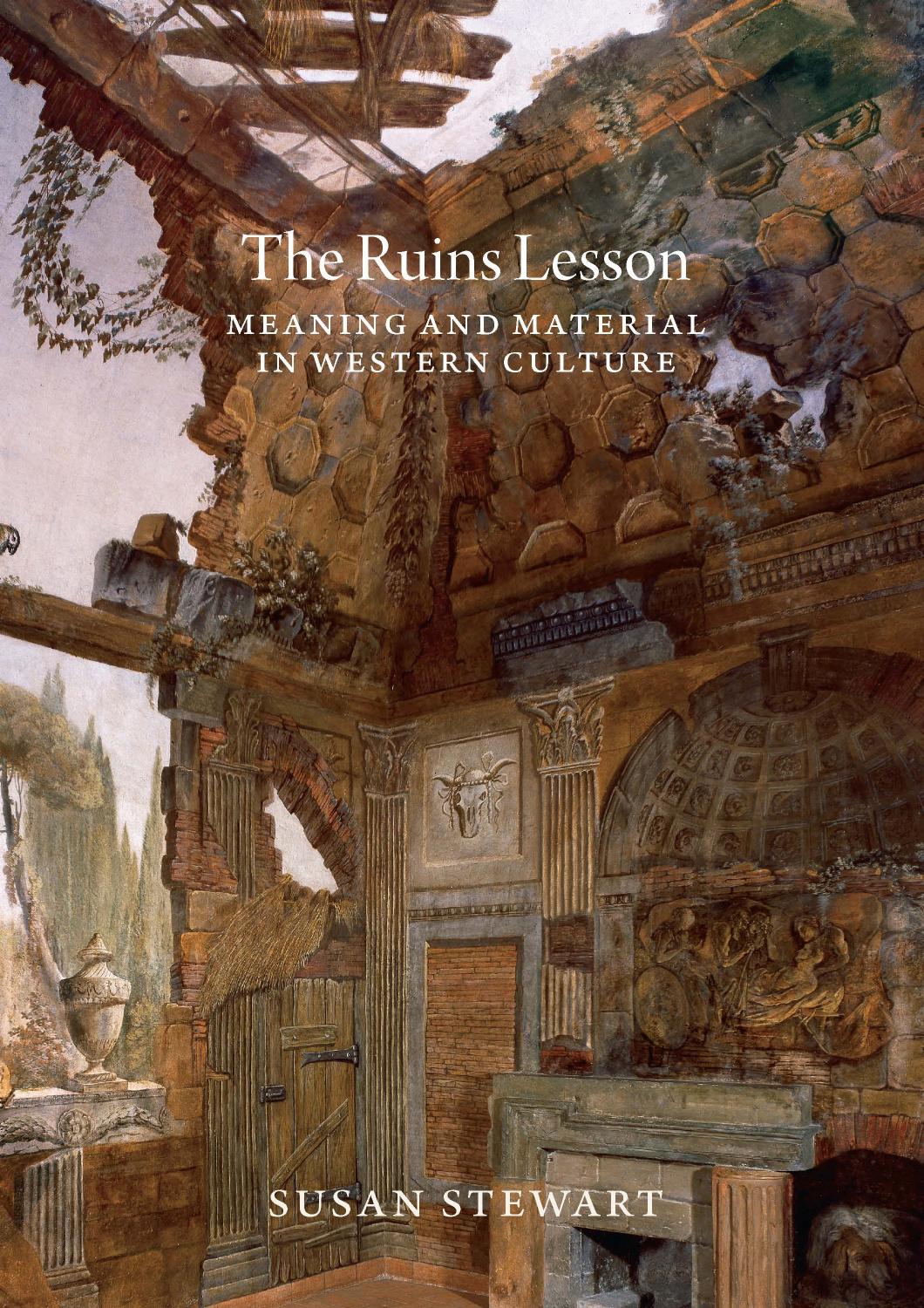

One project of the period, however, brought an unusual experience of ruins indoors into a three-dimensional, room-sized illusion. This was Clérisseau’s 1766 commission from two learned Franciscans, members of the mathematical Order of the Minims, Thomas Lesueur and François Jacquier, to make an interior room a “ruin room” in their monastery of Santa Trinità dei Monti at the top of the Spanish Steps (see plate 9). By this time, Clérisseau had been companion, employee, and drawing teacher to the Adam brothers since his meeting with Robert in 1755, and he, too, had been active in Piranesi’s circle just down the steps from the monastery.34 Lesueur and Jacquier would have been attracted to the idea of an illusionistic ruins room not only because of the zeitgeist brought about by anticomanie, but also because the Minims had long sponsored artistic projects based in mathematics, including the anamorphic frescos commissioned by their seventeenth-century predecessors Emmanuel Maignan and his disciple Father Jean-François Niceron.35

Clérisseau had been a student of Panini, who was “professeur de perspective” during Clérisseau’s early and turbulent tenure at the French Academy. He was close to artists on every side of the debates on classical ruins—a friend to Le Roy and Winckelmann as well as Piranesi. His training in perspective theory served him well at Santa Trinità as he created illusions of receding arcades of pilasters, a coffered ceiling broken open to the sky, foregrounds of niches and urns and misty distant vistas, rustic wooden doors and gridded windows, and great sarcophagi. Whereas most ruins representations survey their landscapes from a vantage point, Clérisseau creates a repertoire of views—glimpsing, peeking, oscillating, and scanning. The viewer is truly surrounded by, and immersed in, ruins.

The room, closed in actuality, seems to open to infinity. A recent study of the space by Cristian Boscaro using three-dimensional laser camera technology reveals the precise measurements Clérisseau used to create his tumbling illusion with such verisimilitude. Today the room is called by the inhabitants of the Sacred Heart convent that now occupies the site, “la stanza del papagallo” (the room of the parrot), for Clérisseau painted a bright parrot perching on an exposed beam beneath the broken wooden planks of a wrecked ceiling.36 The colorful bird draws us toward a consciousness that we are looking at paint and the powers of painting that have lasted by now for hundreds of years; at the same time, it gives a sense that we are present to the actual, within the brief moment when a living thing might perch on forms that are slowly breaking down and disappearing.

The trompe l’oeil ruins frescos of Giulio Romano’s Palazzo del Te in early sixteenth-century Mantua and Domenico Piola and Andrea Seghizzi’s similar seventeenth-century decorations at the Villa Balbi-Durazzo allo Zerbino in Genoa had reveled in much the same way in the illusionistic powers of perspective drawing. Yet such earlier works often used ruins as a backdrop to myth, telling narratives of Gigantomachy in the Palazzo del Te, and of Venus and Enone at the Villa Balbi-Durazzo, largely taken from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Download

The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture by Susan Stewart.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Books & Reading | Comparative Literature |

| Criticism & Theory | Genres & Styles |

| Movements & Periods | Reference |

| Regional & Cultural | Women Authors |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12375)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7757)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7330)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5759)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5756)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5415)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5082)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4935)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4723)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4566)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4548)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4526)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4439)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4097)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4020)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(4006)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3996)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3976)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3844)