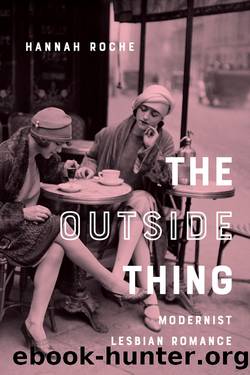

The Outside Thing by Hannah Roche;

Author:Hannah Roche;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Lightning Source Inc. (Tier 3)

5

FROM LESBIAN READING TO BISEXUAL WRITING

Switching Tracks with Djuna Barnes

The very Condition of Woman is so subject to Hazard, so complex, and so grievous, that to place her at one Moment is but to displace her at the next.

âLadies Almanack (1928)

On or about May 1910, Djuna Barnesâs father and paternal grandmother arranged a âcommon-law marriageâ between the seventeen-year-old Djuna and the fifty-two-year-old brother of her fatherâs live-in mistress. According to her grandmother, Zadel, Percy Faulknerâs new âbrideâ had already inherited her familyâs gossip-worthy views on âmarriage & sex questions.â1 She may or may not have regularly engaged in âsex playâ with Zadel, having shared a bed and a âbawdyâ correspondence with her throughout her adolescence.2 She may or may not have lost her virginity to her father, or to âan Englishman three times her age with her fatherâs knowledge and consent.â3 She may or may not have loved her âhusband,â whom she went on to leave after only two months but whose first name later reappeared in a pseudonymously published drama: the character of Ellen in âShe Tells Her Daughterâ (1923) was once âin love with a fellow named Percy.â4

It is startlingly clear, to adopt her own phrasing, that to place Djuna Barnes at one moment is but to displace her at the next. Before so much as a glance at her notoriously challenging writing, it is easy to see why biographers have looked to Barnesâs texts, as critics have looked to Barnesâs life, in their attempts to make sense of âModernismâs least-understood woman writer.â5 There has, until recently, been a tendency to approach Barnes herself as though she were an impossible novel whose elusive answers may one day present themselves. The apparent irregularities and inconsistencies in Barnesâs childhood alone have been shaped, even by Barnes, into a number of linear narratives of causality, varying in plausibility and value. Was Barnesâs âLesbianism,â as Barnes reportedly stated, âthe consequence of her father raping her when she was a very young girl?â6 Or was the âsex playâ between Barnes and Zadel the catalyst for Barnesâs later relationships with women (most notably Thelma Wood, whom Barnes apparently claimed to love âbecause she looked like her grandmotherâ)?7 Biographer Phillip Herringâs suggestion that âperhaps the word âincestâ is too strong a word for what passed between [Djuna and Zadel], which may have been nothing more than good-natured fondlingâ (57) begs further, more pertinent, questions. Setting pseudonyms and misnomers aside, what are the âright wordsâ here? Even if nonfictional and personal documents are to be included in Barnesâs oeuvreâHerring observes that âletters should perhaps be read as literary textsâ (56)âcan it ever be useful to search for a classifiable, âreal,â and âreadableâ Barnes in her writing?

Herring confesses to feeling that â[Barnesâs] textual strategies continued to perform tricks while she hid behind a curtain, smiling at our gropingsâ (xxi). It is tempting to propose that the mock marriage to Percy Faulkner, which involved a version of a wedding ceremony without clergy, can be read as a precursor to the staging and heteronormative performance that would characterize much of Barnesâs writing.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Fine Print (Dreamland Billionaires Book 1) by Lauren Asher(2547)

Fury of Magnus by Graham McNeill(2435)

The Last House on Needless Street by Catriona Ward(2380)

The Rose Code by Kate Quinn(2188)

A Little Life: A Novel by Hanya Yanagihara(2093)

Malibu Rising by Taylor Jenkins Reid(1902)

Luster by Raven Leilani(1892)

The God of the Woods by Liz Moore(1892)

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi(1843)

Moonflower Murders by Anthony Horowitz(1834)

The Lost Book of the White (The Eldest Curses) by Cassandra Clare & Wesley Chu(1679)

This Changes Everything by Unknown(1496)

The Midwife Murders by James Patterson & Richard Dilallo(1471)

The New Wilderness by Diane Cook(1434)

The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante(1424)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1406)

Written in the Stars by Alexandria Bellefleur(1390)

Ambition and Desire: The Dangerous Life of Josephine Bonaparte by Kate Williams(1380)

The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante;(1302)