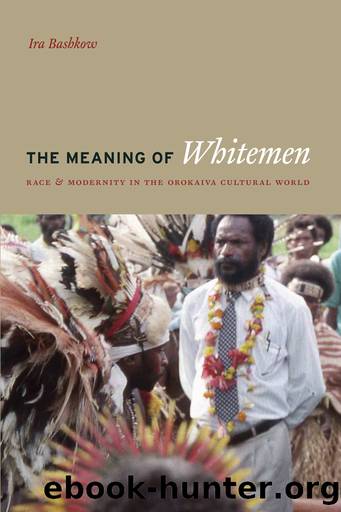

The Meaning of Whitemen by Ira Bashkow

Author:Ira Bashkow [Bashkow, Ira]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Social Science, General, Sociology, Anthropology, Cultural & Social, Ethnic Studies

ISBN: 9780226530062

Google: fCFBDwAAQBAJ

Barnesnoble:

Goodreads: 2466689

Publisher: University of Chicago Press

Published: 2006-07-17T00:00:00+00:00

FIGURE 5.1 ⢠The baby and the stick; the taro plant (adapted from Iteanu 1993a, 34)

It is through food crops that people indirectly âgetâ their rootedness later in life as well. This happens both by eating the foods and by cultivating them. Taro themselves embody rootedness, which is expressed in taroâs heaviness, hardness, and strength. As we saw earlier, Orokaiva gardeners cultivate strong, hard taro by encouraging the plantsâ roots to descend as deeply as possible into the soil, and by allowing mature taro to ripen until they are so strongly rooted that they cannot be moved. A person who eats taro routinely incorporates these qualities. But it is not only by eating ârootednessâ that Orokaiva themselves become rooted; they also become rooted through the fact that their foods must be planted, necessarily on their own lands: they must cultivate their food gardens in order to eat. Peopleâs rootedness in their lands, in other words, is derived from practical and situational as well as mystical and sympathetic relationships. As suggested by Kingsfordâs joke (see chapter 3), Orokaivasâ taro weigh them down with the âheaviness of earthâ because their need to grow it ties them to particular local lands. Orokaiva are tied to their taro, and their taro, in turn, are tied to the ground.

This quality of ârootedness,â then, describes one way that Orokaiva talk about the qualities they derive from and share with their foods. But there is yet another way, which might in contrast be glossed as âexpansiveness,â a quality of mobility that we have seen associated with lightness in persons and with hardness in foods. There is a basic type of conversion from the rootedness of foods to an expansive quality in persons. For one thing, as we have seen, taro that is heavy and hard from being well rooted in the ground produces in people who eat it a deep, heavy sleep that promotes bodily growth or expansion. And when given away in feasting, it is the heaviness of such taro that âpresses downâ its recipients, symbolically vanquishing them, thereby expanding its giversâ name and influence. Thus, the particular qualities of heaviness and hardness that taro receive from rootedness in the ground (gardeners expend enormous effort to get their taro to root deeply) are critical to the expansion of the social person with whom the food is identified (see also Munn 1986).

The main work Orokaiva do is cultivate food that will maintain their bodies, nurture their families, and support their exchange relationships. Peopleâs garden foods are the critical resource that enables them to achieve any large aim. Hospitality and food exchanges wax when peopleâs gardens thrive, and wane when they fail. Men plan their feastsâat which they seek renown, but also risk failure should their foods come up shortâaccording to the state of their gardens, predicting as well as they can the time of greatest abundance, hoping they will not have to call the whole thing off because the crop fell short. Indeed, people themselves grow fat and lean with the seasons of their gardens.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Born to Run: by Christopher McDougall(7120)

The Leavers by Lisa Ko(6945)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5408)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5363)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5173)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5163)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4290)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4177)

Never by Ken Follett(3934)

Goodbye Paradise(3798)

Livewired by David Eagleman(3762)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3368)

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(3071)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3057)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3014)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2919)

Will by Will Smith(2905)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2843)

People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory by Dr. Brian Fagan & Nadia Durrani(2726)