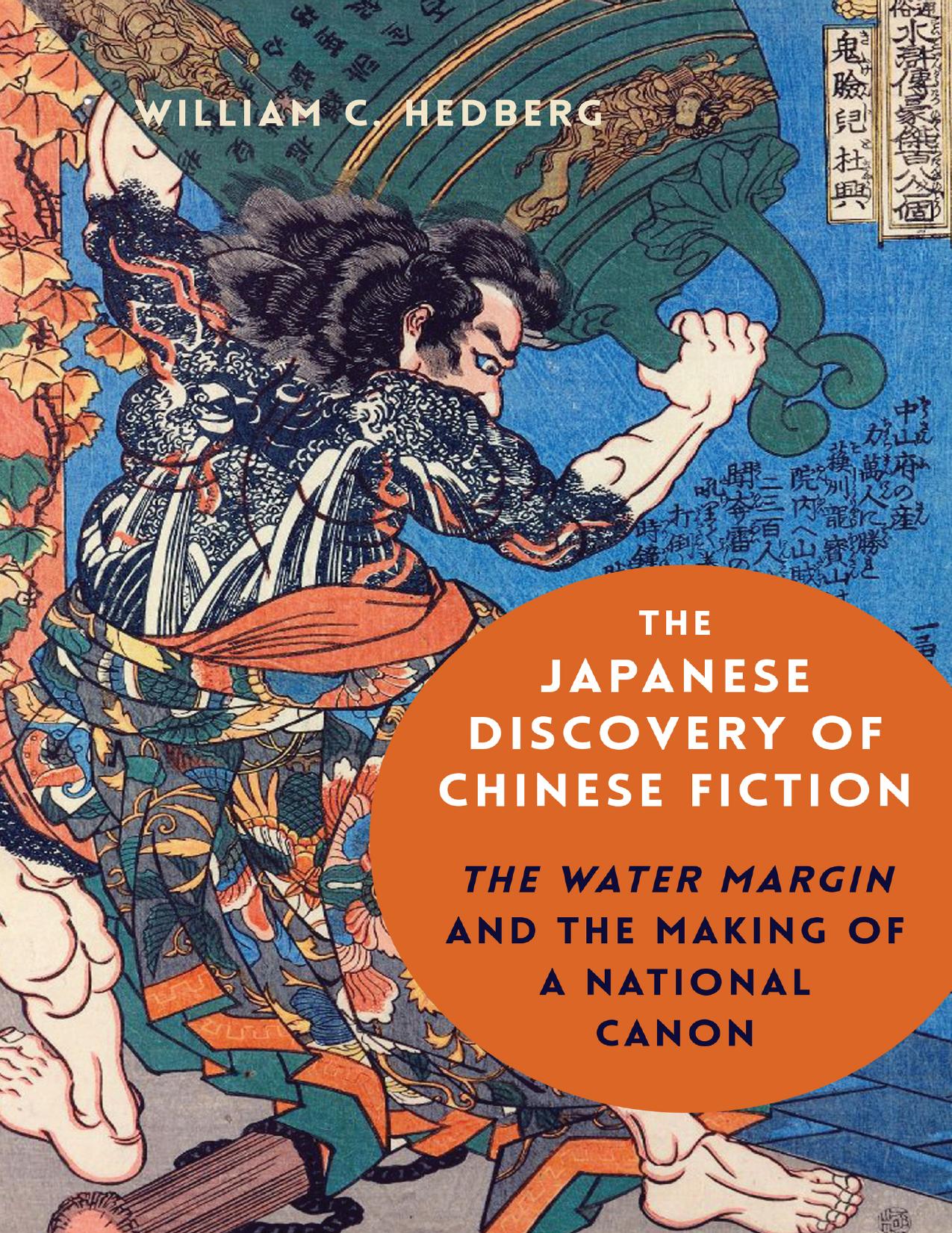

The Japanese Discovery of Chinese Fiction by William C. Hedberg

Author:William C. Hedberg

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Columbia University Press

SUPPRESSING AND FINDING AN AUTHENTIC VOICE OF THE PEOPLE

As Michael C. Brownstein argued in his seminal study of Japanese-literature historiography, Meiji-period histories were often structured as a “romance,” in which a reified Japanese kokutai (embodied in the form of literature) progressed and developed through an agonistic relationship with an opponent: in this case, the “rival kokutai” signified by Sinitic writing.102 A similar narrative strategy is observable in works of Chinese-literature historiography, where historiographers of Chinese literature traced the uneven progression of an authentic and expressive Chinese voice, locked in dialectic combat with the strictures of race, geography, and, paradoxically, the idea of literature itself. As presented earlier, the hallmarks of Meiji- and Taishō-period Chinese-literature historiography might be summarized as follows: the incorporation of development or progress as a central interpretive axis, an emphasis on the antiquity of the Chinese literary tradition in comparison with that of the West, and a concomitant denigration of Chinese efforts to interpret their own literary history. Finally, as the example of Mori Kainan demonstrates, Japanese historians retained a keen interest in traditional Chinese literary thought, even as they labored to fit these “unsystematic” jottings into the mold provided by Western-style historiography.103

A history of the development of literature required the location of a clear point of origin and the creation of a narrative of gradual improvement. In the case of fiction (shōsetsu), many Japanese historians followed Mori Kainan’s lead in “Shina shōsetsu no hanashi” by locating the origin of the novel in the myths, legends, and “fairy tales” of high antiquity. Just as Tsubouchi Shōyō argued that Japan had always possessed a tradition of shōsetsu, Mori traced the genesis of Chinese shōsetsu to the Western Han:

The roots of the word shōsetsu stretch back to the Eastern Han dynasty in Zhang Heng’s Rhapsody on the Western Capital, where we see the line, “The nine hundred volumes of shōsetsu have their roots in the records of Yu Chu.” Yu Chu was the name of a diviner in the service of Emperor Wu of the Han. He knew that Emperor Wu was deeply bedazzled by the lore of gods and immortals, and in order to engage with him, he sought out all manner of marvelous and bizarre tales. He edited them into a collection of nine hundred sections, with the title Stories of the Zhou. If this is true, then shōsetsu arose during the time of Emperor Wu—a period of more than two thousand years ago. Thus, it is no exaggeration to say that of all the countries of the world, China possesses the most ancient tradition of shōsetsu.104

The reign of the gullible Han emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BCE)—described in classical histories as highly susceptible to manipulation at the hands of wandering diviners and magicians—was a popular point for establishing the “beginning” of fiction, but other writers pointed toward the imaginative and often fanciful parables of the Zhuangzi or Liezi as potential points of origin. Analysis of these early “sprouts” (hōga) was usually followed by discussion of Six Dynasties–period

Download

The Japanese Discovery of Chinese Fiction by William C. Hedberg.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African | Asian |

| Australian & Oceanian | Canadian |

| Caribbean & Latin American | European |

| Jewish | Middle Eastern |

| Russian | United States |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12375)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7757)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7326)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5759)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5754)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5413)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5080)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4935)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4723)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4565)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4547)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4526)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4439)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4097)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4018)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(4002)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3996)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3976)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3844)