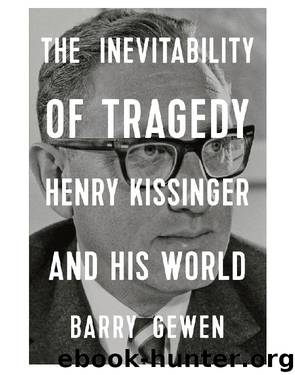

The Inevitability of Tragedy by Barry Gewen

Author:Barry Gewen

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Published: 2020-03-18T00:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER FIVE

VIETNAM

IN THE EARLY 1950S, HANS MORGENTHAU TOOK TIME OFF from his duties at the University of Chicago to accept an appointment as a visiting professor at Harvard, where he taught a graduate seminar on international relations. Among his students were such future giants in the field as Zbigniew Brzezinski, Samuel Huntington, and Stanley Hoffmann. But the student who stood out above them all was Henry Kissinger, already something of a legend on campus for his dense, gargantuan undergraduate thesis on Spengler, Kant, and Toynbee. It was said that his dissertation adviser, the formidable William Yandell Elliott, had read less than a third of it before awarding Kissinger a summa cum laude (whether out of admiration or frustration was not said). Morgenthau was told to make the acquaintance of the promising young man, 19 years his junior, and he came away from the encounter impressed enough to consider Kissinger for a position at Chicago. But Kissinger stayed at Harvard to work on his doctoral dissertation and so Morgenthau became Kissinger’s “informal mentor” from a distance.

The dissertation was completed in 1954 and published three years later as A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace, 1812–22. It was audacious in many respects, but perhaps no more so than in its effort to understand the present by examining the past. Most of Kissinger’s contemporaries in the political science department were employing contemporary methodology to analyze modern issues, in particular the impact of nuclear weapons on foreign policy (a subject that Kissinger would later make his own), and some even suggested that the unconventional Kissinger might think about transferring to the history department. But like Morgenthau and unlike so many political scientists of the time, Kissinger believed the study of history was essential for an understanding of international relations. The past was never past. History taught complexity and contingency, the way political and military leaders went about selecting among indeterminate options in the particular circumstances they faced and the mistakes they often committed as individuals making individual choices. There was no escaping uncertainty; tragedy was an ever-constant presence in human affairs. One obtained from the past not abstract formulas to be applied mechanically to modern-day problems but a flexible awareness of the human condition that could enrich the decision-making process. “History teaches by analogy, not identity,” Kissinger wrote. “This means that the lessons of history are never automatic.” Needless to say, Kissinger was no more enamored of quantitative thinking than Morgenthau.

In the case of A World Restored, Kissinger saw parallels between the Congress of Vienna, which concluded the Napoleonic wars, and the Paris Conference of 1919 that followed World War I—the first a measured response that resisted calls for vengeance and led to a century of relative calm, the second a self-righteous attempt to impose a punitive settlement that produced a “victors’ peace” and resulted in disaster. Other diplomatic parallels Kissinger perceived related more directly to his immediate present. He was writing about Europe in the early nineteenth century, but at

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Arms Control | Diplomacy |

| Security | Trades & Tariffs |

| Treaties | African |

| Asian | Australian & Oceanian |

| Canadian | Caribbean & Latin American |

| European | Middle Eastern |

| Russian & Former Soviet Union |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19046)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12185)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8889)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6875)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6264)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5786)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5737)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5496)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5429)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5213)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5141)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5080)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4950)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4919)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4778)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4740)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4699)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4502)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4484)