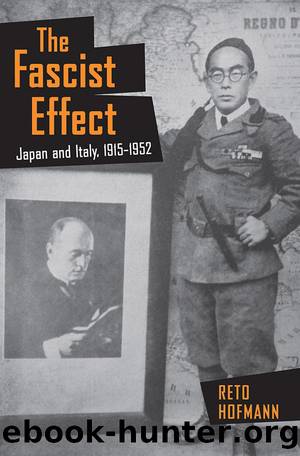

The Fascist Effect by Hofmann Reto;

Author:Hofmann, Reto;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Lightning Source Inc. (Tier 3)

Published: 2015-05-07T00:00:00+00:00

Celebrating Fascist Italy

Japan’s descent into total war ushered in profound changes to Japanese politics and society. The police apparatus increased its surveillance of the press and ordinary citizens, often with brutality. Labor laws mobilized men, women, and even children into compulsory factory work in industries that were crucial to the war effort. Consumer goods progressively vanished from stores; food became scarce.8 And yet, as Ken Ruoff has demonstrated, in wartime Japan privations coexisted with celebrations. The state kept its citizens informed not only of major military exploits—first in China, then in the Pacific—but, in keeping with the heightened sense of history, poured vast resources into cultural events, in particular the 1940 festivities around the 2,600th anniversary of the mythical founding of Japan.9 Promoted by government institutions and supported by civil groups, a celebratory mood often pervaded public life in what was designated as an epoch-making moment.

Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany were integrated into these performances. The half-decade stretching from 1937 to 1943 represented a new phase in the relations between the three countries, a period in which the fascist powers enjoyed unprecedented exposure in the journalistic, academic, and official debates.10 Starting with Italy’s joining of the Anti-Comintern Pact in November 1937, sealed the previous year by Japan and Germany, the government began to stage commemorative events to celebrate the important dates in the Axis calendar—anniversaries of pacts or military victories—but also to honor individuals and representatives of these countries. Through these campaigns, Japanese officialdom sought to conjure a cordial image of Italy and Germany. Kawai Tatsuo, the head of the Foreign Ministry Information Section (Gaimushō Jōhōbu) and postwar ambassador to Australia, expressed the official stance when Italy joined the Anti-Comintern Pact, asserting that it was “a natural outcome for people [kokumin] with a spiritual proximity to get close and seek one another” and that, as this friendship grew, they would advance “world civilization and peace.”11

In the case of Italy, it is remarkable how fast official and public discourse shifted from one of apprehension and hostility during the invasion of Ethiopia to one of support and sympathy in the years after 1937. Tacit realignment had, in fact, started even earlier. On May 9, 1936, only four days after Italian forces had entered the Ethiopian capital, a functionary of the Japanese Embassy in Rome paid a visit to the Italian Foreign Ministry. He “expressed congratulations for the surrender of Addis Ababa,” the ministry recorded, “adding that the congratulations of the Japanese Government ought to be considered among those truly sincere.”12 The enthusiastic Japanese official may have overstated the case, as a substantial pro-British faction in the foreign ministry opposed an alliance with Italy. Nonetheless, as argued by the diplomatic historian Valdo Ferretti, the Japanese Foreign Ministry spearheaded a conciliatory policy toward Italy, proceeding to improve relations with Rome through a rapid series of diplomatic agreements.13 On November 18, 1936, Japan became the first power to recognize the Italian annexation of Ethiopia and downgraded its embassy there to the rank of a consulate.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anarchism | Communism & Socialism |

| Conservatism & Liberalism | Democracy |

| Fascism | Libertarianism |

| Nationalism | Radicalism |

| Utopian |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16608)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11485)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(7782)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(5753)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5029)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4817)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(4785)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4440)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(4412)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(4404)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4392)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4336)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4070)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4025)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4008)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(3875)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(3869)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3773)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3725)