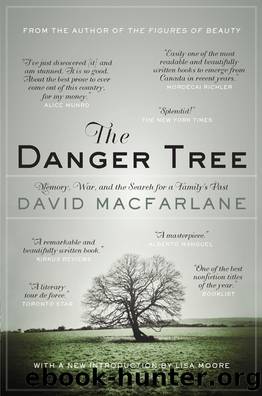

The Danger Tree by David Macfarlane

Author:David Macfarlane [Macfarlane, David]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781443416009

Publisher: HarperCollins Canada

Published: 1991-10-15T00:00:00+00:00

Stan Goodyear wouldnât be going west. He wouldnât be buying a ticket home. Stan would be all right.

SEVEN

Our Island Story

On New Yearâs of 1917 General Sir Douglas Haig was promoted to the rank of field marshal by King George V. The King described the promotion as âa New Yearâs gift from myself and the country.â This gratitude was not entirely shared by the British prime minister, David Lloyd George. He saw in Haig the embodiment of the warâs strange ability to turn reason on its head. In Lloyd Georgeâs view, Haig was largely responsible for six hundred thousand Allied casualties during the four useless months of the Somme offensive in 1916. Lloyd George wasnât a soldier. But he suspected that waiting to see which side had the greater supply of young men was not the most intelligent war plan available.

Haig disagreed. Wars were wars; battles were battles; soldiers were soldiers. The arrival of the twentieth century had not changed the fundamental rules of an ancient game. âI feel that every step in my plan has been taken with the Divine help,â he wrote to his wife on the eve of the July 1 drive.

Godlessness had found a prophet. Before supper on July 1, 1916, twenty thousand British soldiers were dead. The German line had scarcely budged.

A few days later, Haigâs strategy was unintentionally summarized with stupefying irony by one of his divisional commanders, Major-General Sir Beauvoir de Lisle. The Newfoundland Regiment served in the 88th Brigade of de Lisleâs 29th Division. After the battle of Beaumont Hamelâin which 710 of the Regimentâs 801 active soldiers were either killed or wounded or went missing within their first half-hour of battle on July 1âde Lisle sent a note to Sir Edward Morris, the prime minister of Newfoundland. He might have been describing the entire war. âIt was a magnificent display of trained and disciplined valor, and its assault only failed of success because dead men can advance no farther.â

By early November of 1916, when the Somme offensive finally sputtered out, the largest advance along the strategically pointless front was no more than five miles. In any other context, Haigâs plan would have been recognized as idiocy. But the war, which was virtually without victory or defeat, had a way of justifying the bloody mess in between. Despite all evidence to the contrary, the battles in France and Belgium continued to be discussed, evaluated, and planned in terms that Wellington would not have found entirely unfamiliar. But there was one clearly understood difference between warfare in the nineteenth century and warfare in the twentieth: at Waterloo, one side won and the other lost; in the prolonged stalemate of the trenches, either side could claim victory when a victory was needed. If an offensive failed, it could be called a gallant stand. If defences collapsed, the advancing enemy could be reported as stranded on the bulge of a salient, threatened now on three sides and certainly doomed as a result. If 800 soldiers were lost in a morningâs skirmish, it could reasonably be claimed that the other side had lost 1,000.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10937)

The Templars by Dan Jones(4203)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4101)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4035)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3745)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3539)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3471)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3458)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3101)

12 Strong by Doug Stanton(3066)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(2744)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(2658)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(2618)

The Art of War Visualized by Jessica Hagy(2429)

Hitler's Flying Saucers: A Guide to German Flying Discs of the Second World War by Stevens Henry(2309)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(2226)

The Second World Wars by Victor Davis Hanson(2140)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2079)

Tobruk by Peter Fitzsimons(2070)