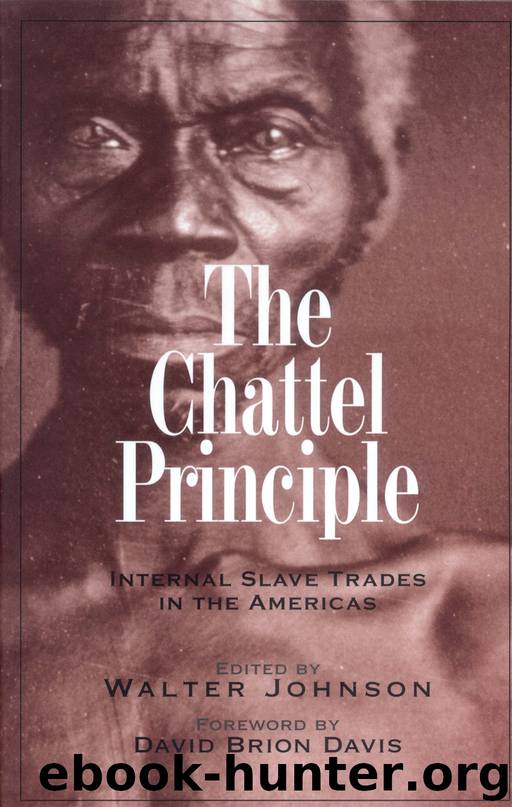

The Chattel Principle by Walter Johnson

Author:Walter Johnson

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2004-04-14T16:00:00+00:00

9

Grapevine in the Slave Market African American Geopolitical Literacy and the 1841 Creole Revolt

PHILLIP TROUTMAN

In November 1841, a group of at least nineteen enslaved African American men held aboard the brig Creole effected a successful inversion of United States slave traders’ network of communication and transportation. Bound from the Chesapeake to New Orleans in the domestic U.S. slave trade, they violently captured control of the ship and forced the crew to chart a course for Nassau, Bahamas. There, with the aid of black Bahamians and British colonial officials, they gained freedom along with all but five of their enslaved shipmates, 130 in all. White contemporaries tended to view the Creole “incident” in terms of its contribution to an international trade conflict between the United States and Great Britain. Its chief historian, Howard Jones, has made clear its importance in that regard. The revolt, however, is at least as important for what it illustrates about how enslaved African Americans worked to acquire, disseminate, and apply geographic and geopolitical knowledge and information—what I call geopolitical literacy—and what that might mean for their broader Afro-American consciousness. By contrast to the more famous bid for freedom carried out in 1839 by kidnapped Mendi aboard the Cuban schooner Amistad, the Creole revolt was successful in its initial stage. Key to these rebels’ remarkable (and unique) success were their ability to create and articulate conceptual maps of slavery and freedom in the African Atlantic and their application of navigation skills to transgress the boundaries of that political landscape.1

The Amistad Africans, like all those enslaved for the transatlantic trade, had been alienated from their known world and were unfamiliar with the maritime geography of the Americas. Vulnerable to duplicity on the part of their captive crew, they found themselves directed not east, back to Africa, as they had demanded, but rather north, up the American coast. The African Americans aboard the Creole, by contrast, knew their geopolitical context, knew where to find freedom within it, and knew how to effect their passage there. Although alienated from their families and communities by the interstate slave market, the Creole rebels nonetheless remained within the larger world of American slavery made known to them by their use of the grapevine and made navigable by their maritime skills. They operated a covert network of information and knowledge across and within the overt networks of commerce built by interstate slave traders, then used that information to carry out the most successful African American attempt at freedom in the history of the United States before the Civil War.

The Creole revolt exposes the ways people and knowledge moved in and out of what we usually think of as the bounded spaces of American slavery and even within the most tightly controlled spaces of incarceration, the holding cells of the domestic slave trade. When one was a slave, one was in the slave market. That was the meaning of the chattel principle, as African American autobiographers made clear again and again.2 Yet many historians continue to marginalize the slave market as a sideshow, as if it were somehow peripheral to slavery.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| General | Discrimination & Racism |

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7694)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5432)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5409)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4566)

The Sports Rules Book by Human Kinetics(4379)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(4375)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4243)

Captivate by Vanessa Van Edwards(3838)

Mummy Knew by Lisa James(3686)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3537)

The Worm at the Core by Sheldon Solomon(3486)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3463)

The 48 laws of power by Robert Greene & Joost Elffers(3254)

Suicide: A Study in Sociology by Emile Durkheim(3019)

The Slow Fix: Solve Problems, Work Smarter, and Live Better In a World Addicted to Speed by Carl Honore(3007)

The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell(2914)

Humans of New York by Brandon Stanton(2868)

Handbook of Forensic Sociology and Psychology by Stephen J. Morewitz & Mark L. Goldstein(2704)

The Happy Hooker by Xaviera Hollander(2686)