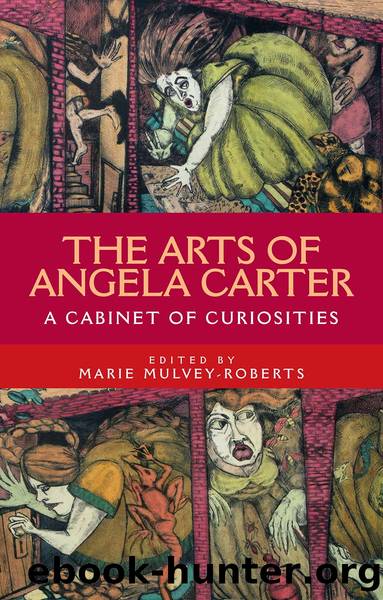

The Arts of Angela Carter by Marie Mulvey-Roberts;

Author:Marie Mulvey-Roberts;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Manchester University Press

7

Angela Carter’s ‘rigorous system of disbelief’: religion, misogyny, myth and the cult

Marie Mulvey-Roberts

IN RESPONSE TO LORNA Sage’s question in a 1977 interview as to whether ‘one needs still to be anti-God’, Angela Carter was in no doubt, saying, ‘Oh yes! It’s like being a feminist, you have to keep the flag flying. Atheism is a very rigorous system of disbelief, and one should keep proclaiming it. One ought not to be furtive about it’ (Sage 1977: 57). Carter debunked religion through two short stories demystifying the Fall, and another re-evaluating the representation of Mary Magdalene in European art. She also produced an iconoclastic film on the life of Christ through painting called The Holy Family Album (1991) and satirized religious practice from medieval Catholicism in The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman (1972) to that of a modern Messiah in The Passion of New Eve (1977), via a re-imagining of Charles Manson’s infamous sex cult, responsible for the brutal murder of the film actress Sharon Tate, discussed in detail here for the first time. Carter’s atheism informed her feminist, political and ideological outlook on the world, while her approach to religion was part of her ‘demythologising business’ (Carter, 1997c: 38). She used radical scepticism to attack religion which, in having been built on myths, she saw as ‘extraordinary lies designed to make people unfree’ (38), a witty inversion of Christ’s dictum: ‘And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free’ (John 8:32, KJV).

As a teenager, Carter freed herself from the Anglican faith of her mother, which had involved attending a church service every Sunday. By the start of the 1960s, when she moved to Bristol, she was an avowed atheist.1 Her brother Hugh responded rather differently to his upbringing by becoming an accomplished church organist and choir master.2 The baroque extravagances of his sister’s writing may have been a reaction against the Calvinism on the paternal side of her family. Her father, Hugh Stalker, came from the Calvinist north east of Scotland, the Aberdeenshire ‘godly town’ (1997b: 17) of Macduff and her great-great grandmother had ‘the stern face of a Kirk-goer’ (15). Her paternal grandfather, however, was ‘the village atheist’ (18), though not of sufficient conviction to refrain from hedging his bets over the after-life by leaving five pounds in his will to the minister. To his annoyance, his wife treated the Sabbath as a day of rest, and every week piled Sunday’s washing into a bucket for the next day. His granddaughter continued his legacy in the belief that ‘nothing is sacred’ (108), though she did admit that there is ‘something sacred about the cinema’, as a place of shared revelation (Evans: 1992). Carter’s atheism was bound up with ‘an absolute and committed materialism ‒ i.e., that this world is all that there is and in order to question the nature of reality one must move from a strongly grounded base in what constitutes material reality’ (1997c, 38; emphasis in original). For this reason, she

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11049)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(6852)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(5878)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(4723)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(4576)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4213)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(3991)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(3972)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3802)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(3711)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(3671)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(3586)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(3514)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(3436)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(3367)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3311)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3226)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3218)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3213)