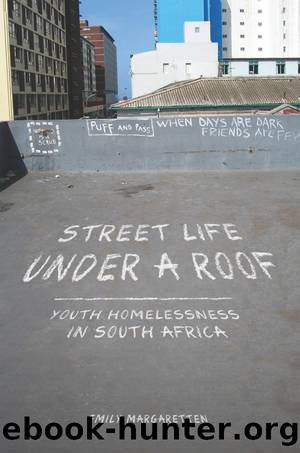

Street Life under a Roof by Emily Margaretten

Author:Emily Margaretten [Margaretten, Emily]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Social Science, General, Anthropology, Cultural & Social, Gender Studies, History, Africa, South, Republic of South Africa

ISBN: 9780252097690

Google: TZWJCgAAQBAJ

Publisher: University of Illinois Press

Published: 2015-09-15T05:45:42+00:00

âIt's the truth.â Skora, a nineteen-year-old male living inside Point Place, is emphatic. âI'm telling you, I see things. The girls I stay with, I know them. They're sleeping with many boys, and they date many boys.â

I am not easily convinced by this one-way indictment, and so I ask Skora, âBut what about the boys in Point Place?â

âAnd the boys, too,â Skora agrees. âBut it's the boysâ thing.â

âWhat do you call a boy who sleeps around?â I ask.

âIt's the same as the girls,â Skora replies. âHe's an isifebe [bitch]. In the olden days, too, our fathers, our great-grandfathers, they had isithembu [polygamy].â

âDid you call them amasoka [pl. of isoka]?â I inquire.

âYeah!â

âIs it good to be an isoka?â

âNo,â Skora responds. âIt's not right when a person is poor, because you're going to make the girl suffer.â

In the above conversation, Skora draws attention to the sexual promiscuity of the Point Place females. He then concedes that the males, too, engage in numerous love affairs. He refers to the boys, like the girls, as bitches but justifies their behavior as being a male âthing,â a prerogative passed down from their fathers and grandfathers, linked to the tradition of polygyny. Along these lines, Skora denounces the sexual exploits of the isoka as a problem not of gender inequality but of economic affordability. His explanation of why it is better not to have more than one girlfriendâor a girlfriend at allâis a common one among the Point Place males. They recognize that attracting a girlfriend for a day differs substantially from maintaining a girlfriend. Their insufficient earnings impede their ability to secure a long-lasting relationship. As Musikayisa, a twenty-one-year-old male, narrates, âI don't need a girlfriend because I'm barely surviving. Now if I get a girlfriend, what can I do with her? She'll want things. Now my money is too small to support her and me. Yeah, that's why.â

To support a girlfriend requires more than a few drinks or a few rand. It requires ongoing sustenance and material provisions that the Point Place boys often refer to through the idiom of foodâparticularly staple food. Such maintenance can be tiring. Twenty-seven-year-old Khaya, for instance, feels obliged to âthinkâ for his girlfriend. No matter how meager his provisions, he must share them equally. âYou have to think for them [girlfriends]. Every time you get something small, you have to take it to her. Sometimes if it's two slices [of bread], you have to take it up there to her room.â Although Khaya finds girlfriends wearisome, others, like eighteen-year-old Sandlana, take pleasure in the sustenance of these kinds of relationships: âI like to give that girl money, you see. If I give her money, she wants to eat that money with me, to share with me. And she, too, if she gives me money, I want to eat with her.â The nourishment derived from these types of relationships reflects a broader conceptualization of nakana: of taking care of one another.

Like the Point Place females, the males also link nakana to acts of domesticity and shared reciprocity.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Central Africa | East Africa |

| North Africa | Southern Africa |

| West Africa | Algeria |

| Egypt | Ethiopia |

| Kenya | Nigeria |

| South Africa | Sudan |

| Zimbabwe |

Goodbye Paradise(2974)

Men at Arms by Terry Pratchett(2408)

Tobruk by Peter Fitzsimons(2065)

Pirate Alley by Terry McKnight(1911)

Arabs by Eugene Rogan(1841)

Borders by unknow(1791)

Belonging by Unknown(1473)

The Biafra Story by Frederick Forsyth(1327)

It's Our Turn to Eat by Michela Wrong(1305)

Botswana--Culture Smart! by Michael Main(1239)

A Winter in Arabia by Freya Stark(1226)

Gandhi by Ramachandra Guha(1198)

Coffee: From Bean to Barista by Robert W. Thurston(1184)

Livingstone by Tim Jeal(1154)

The Falls by Unknown(1143)

The Source by James A. Michener(1137)

The Shield and The Sword by Ernle Bradford(1102)

Egyptian Mythology A Fascinating Guide to Understanding the Gods, Goddesses, Monsters, and Mortals (Greek Mythology - Norse Mythology - Egyptian Mythology) by Matt Clayton(1089)

Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles by Richard Dowden(1080)