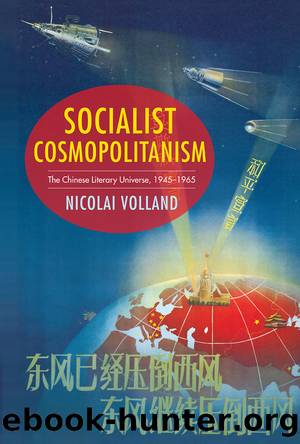

Socialist Cosmopolitanism by Nicolai Volland;

Author:Nicolai Volland;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Lightning Source Inc. (Tier 3)

6

MAPPING THE BRAVE NEW WORLD OF LITERATURE

In the early 1950s, China underwent a revolution of its conceptualization of the world and the PRC’s place therein that was no less dramatic than the one that had occurred at the turn of the twentieth century.1 This revolution of the spatial imagination extended from political to cultural and literary space. The patterns of literary production and consumption taking shape after 1949 were grounded in new practices of circulation, of people as well as texts; they generated modes of appropriation and transculturation that reshaped textual practice; and they ultimately found expression in a new understanding of the world at large. China’s entering of the socialist literary universe redefined its being-in-the-world and its interaction with the world; it could not but transform also the nation’s image of the world.

The new spatial imagination arising after 1949 triggered a radical redrawing of the literary world map. This bold, new cartography of culture identified countries and continents, but also blocs and borders, spatial units as well as new structuring principles governing this new world order. It redefined global hierarchies and power relationships, and inverted customary notions of center and periphery. The emerging literary world map, in other words, embodied the counterhegemonic assertiveness that undergirds socialist cosmopolitanism. So what were the constituent parts of this world map? Which patterns of borders and alliances did it reveal? And where on this map was the young PRC to be found? As the 1950s progressed and the Cold War order hardened, new fault lines began to appear. How did the seismic movements beneath the crust of this brave new world affect the projections of the map? All of these questions, this chapter will show, ultimately go to the core of New China’s cosmopolitan agenda.

The effort to redefine China’s position within the emerging world order of the Cold War era necessitated a reorientation of the nation’s global outlook, of its place vis-à-vis neighbors and enemies, allies and adversaries. In the political sphere, massive propaganda campaigns sought to drive home the new geopolitical and ideological realities, and to implant them firmly in the consciousness of the people. Newspapers, radio broadcasts, and educational institutions produced a constant stream of information that explained, evaluated, and affirmed these new realities, which gained persuasiveness by the sheer power of constant repetition.2 On the linguistic level, a range of novel nouns and adjectives—such as meidi 美帝, the shorthand for “American imperialism” (Meiguo diguozhuyi 美國帝國主義), and more generally for the United States itself—entered everyday language and thus the nation’s collective subconscious.3 Maps in the print media, in textbooks and on wall newspapers across Chinese cities and towns, visualized the new geography. Translating the tangible space of political boundaries and ideological demarcation lines into an imagined space that would reconfigure the Chinese perception of the world at large, however, remained a challenge for the young regime. Cultural production was at the forefront of the Cold War revolution in spatial imagination, in the redrawing of the mental world map. In particular, the

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Ancient & Classical | Arthurian Romance |

| Beat Generation | Feminist |

| Gothic & Romantic | LGBT |

| Medieval | Modern |

| Modernism | Postmodernism |

| Renaissance | Shakespeare |

| Surrealism | Victorian |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11032)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(6836)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(5870)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(4716)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(4563)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4204)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(3982)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(3968)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3788)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(3704)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(3662)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(3578)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(3505)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(3429)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(3358)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3300)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3220)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3212)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3206)