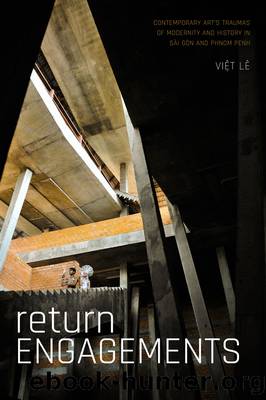

Return Engagements by Việt Lê

Author:Việt Lê

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Duke University Press

Sew What?

We cannot put things into perspective. Like the African American feminist artist Faith Ringgold (b. Harlem, 1930), Seckon uses fabric and paint to tell complex stories using a flat âfolkâ painting technique that disregards perspective. Ringgoldâs large painted âstory quiltsâ critique race and gender issues within dominant Western society with wit and humor, often referencing art history. For instance, her large 1991 story quilt The Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles (acrylic on canvas, tie-dyed, pieced fabric border, 74 Ã 80 inches) depicts a group of African American women holding up their sunflower quilt in a vast field of sunflowers as Vincent Van Gogh stands in the background to the left, holding a bouquet of, yes, sunflowers. They are framed by buildings of the village of Arles, the famous artistâs refuge (he created more than three hundred images of it), rendered in Van Goghâs signature vibrant blues and yellows. Ringgold was among the first Western female artists to use womenâs âcraft,â blurring the line between high and low art, challenging long-held masculinist traditions of what is considered fine art. Through her work she has questioned art institutions, which often omitted minority perspectives.

Quilting has a long history for African Americans. African women adapted quilting from menâs traditional weaving in Africa as they entered America as slaves. The slave community used quilts for various purposes, including the conservation of individual and collective memories, warmth, storytelling, and as message guides for the Underground Railroad to direct slaves north to freedom. Inspired by Tibetan Buddhist tangkas, Ringgold started sewing borders around her paintings, which led to her first story quilt.22 The portable tangkasâoften depicting deities, Buddhaâs trials and tribulations, and the Wheel of Lifeâare usually painted on cotton duck or silk and quilted or embroidered. Ringgold mixes Eastern and Western traditions and âhighbrowâ and âlowlyâ visual references in her contemporary work.

Seckon also blurs the boundaries between craft and fine art, combining sewing, collage, stitching, and painting. He heartily embraces sewing and patching, dismissing the idea that it is mere womenâs work. Here, gender boundaries are fluid. Cambodia, like the rest of Indochina, has already been seen as feminine entity by its colonizers, by the rest in the West. Akin to Ringgoldâs early artistic sewing collaborations with her late mother, Seckonâs work gains inspiration from his motherâs sewing and patching. Her heavy skirt still weighs heavy on his mind. Patching is a spiritual activity; mending is meditationâcobbling tattered pasts, collaging blood-stained painful fragments into a semblance of hope.

A country torn asunder can only scramble to patch, sew together its future, regardless of how bleak. Basic sewing employs approximately 700,000 of Cambodiaâs fifteen million people, many of whom work forty-eight-hour weeks and send remittances to family members in the countryside who survive on less than a dollar a day. In October 2010, thousands of Cambodian garment workers went on a weeklong strike in Phnom Penh for higher wages. My trilingual friend Socheat earned about $60 a month working in a factory. He had to quit his studies to support his widowed mother; his father and brother were casualties of the civil war.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Twisted Games: A Forbidden Royal Bodyguard Romance by Ana Huang(4028)

Den of Vipers by K.A Knight(2701)

The Push by Ashley Audrain(2698)

Win by Harlan Coben(2665)

Echo by Seven Rue(2246)

Baby Bird by Seven Rue(2213)

Beautiful World, Where Are You: A Novel by Sally Rooney(2180)

A Little Life: A Novel by Hanya Yanagihara(2151)

Iron Widow by Xiran Jay Zhao(2125)

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam(2099)

Midnight Mass by Sierra Simone(2014)

Bridgertons 2.5: The Viscount Who Loved Me [Epilogue] by Julia Quinn(1794)

Undercover Threat by Sharon Dunn(1791)

The Four Winds by Hannah Kristin(1773)

Sister Fidelma 07 - The Monk Who Vanished by Peter Tremayne(1668)

The Warrior's Princess Prize by Carol Townend(1631)

Snowflakes by Ruth Ware(1600)

Dark Deception by Rina Kent(1570)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1553)