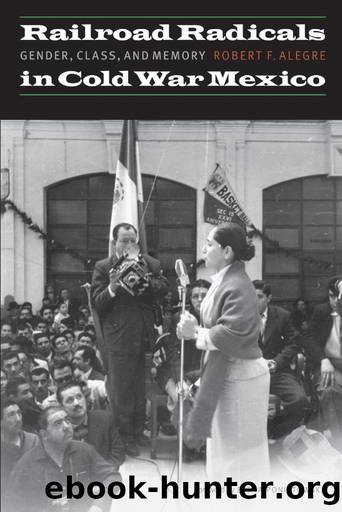

Railroad Radicals in Cold War Mexico: Gender, Class, and Memory by Robert F. Alegre

Author:Robert F. Alegre [Alegre, Robert F.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 978-1-4962-0964-1

Publisher: University of Nebraska Press

Published: 2018-07-14T16:00:00+00:00

4

The “War of Position”

The Making of a Strike

Mariachi bands filled union locals across the country, singing and strumming their guitars for workers celebrating the return of democratic unionism. The day after the election of Demetrio Vallejo to the post of STFRM general secretary, workers walked off the job, not on strike but to welcome their new, independent union leaders. Rieleros had proven to be the ultimate cabrones, the main machos, having beaten the suit-and-tie-wearing charros by leaning on one another and shutting down the rails. Their wives, sisters, and daughters — no less elated — took leading roles, making use of masculine codes to push their men to fight. These men and women celebrated their own efforts in the grassroots movement that was just getting started.

Rather than placate union activists, the August victory further radicalized railway families. Rieleros and rieleras came to embrace the virile militancy exhibited by rieleros who clandestinely organized in the early 1950s. Workers became more rebellious with their newfound independence at work and within the union, using their clout to support demands now made by teachers and students, as well as petrol, telegraph, and electrical workers. Women and men continued to take over city streets, turning them into sites of political theater. Independent STFRM leaders — far from directing the rank and file — now had to figure out how to contain their enthusiasm. The new leadership had to juggle negotiating with railroad companies while restraining a militant rank and file ready to strike at any sign of company inflexibility. In the context of railway gender ideology, the company now appeared effeminate — vulnerable, unable to ward off demands made by rieleros and rieleras. How could Vallejo and other STFRM leaders temper grassroots militancy without seeming to be in cahoots with the government?

This chapter argues that FNM and STFRM officials spent the last months of 1958 engaging in a war of position, presenting their case in periodicals and on streets in order to win public support. Philosopher Antonio Gramsci’s concept of war of position is useful for understanding how railway activists battled the FNM for public support through the use of the press and by occupying public spaces. For Gramsci, the war of position describes defensive tactics employed by workers against the ruling class.1 These tactics can be violent, such as trench warfare, or nonviolent, such as boycotts. In either case, activists must engage civil society and win over the masses, including other workers, in order to be victorious. This last point underscores the contingent quality of social identity — that it is not given but made — as well as the contingent character of political struggle. Workers do not share essential interests that automatically lead them to support working-class movements.2 Labor activists must win workers as well as others to their side. In 1958 and 1959, railroad and other striking workers constructed a sense of unity based on their struggles to democratize their respective workplaces and union. The challenge was to persuade those not engaged in industrial labor to view their movement as just.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Arms Control | Diplomacy |

| Security | Trades & Tariffs |

| Treaties | African |

| Asian | Australian & Oceanian |

| Canadian | Caribbean & Latin American |

| European | Middle Eastern |

| Russian & Former Soviet Union |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16623)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11489)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(7788)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(5772)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5037)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4824)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(4789)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4447)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(4418)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(4415)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4398)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4342)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4077)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4032)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4012)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(3881)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(3872)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3782)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3731)