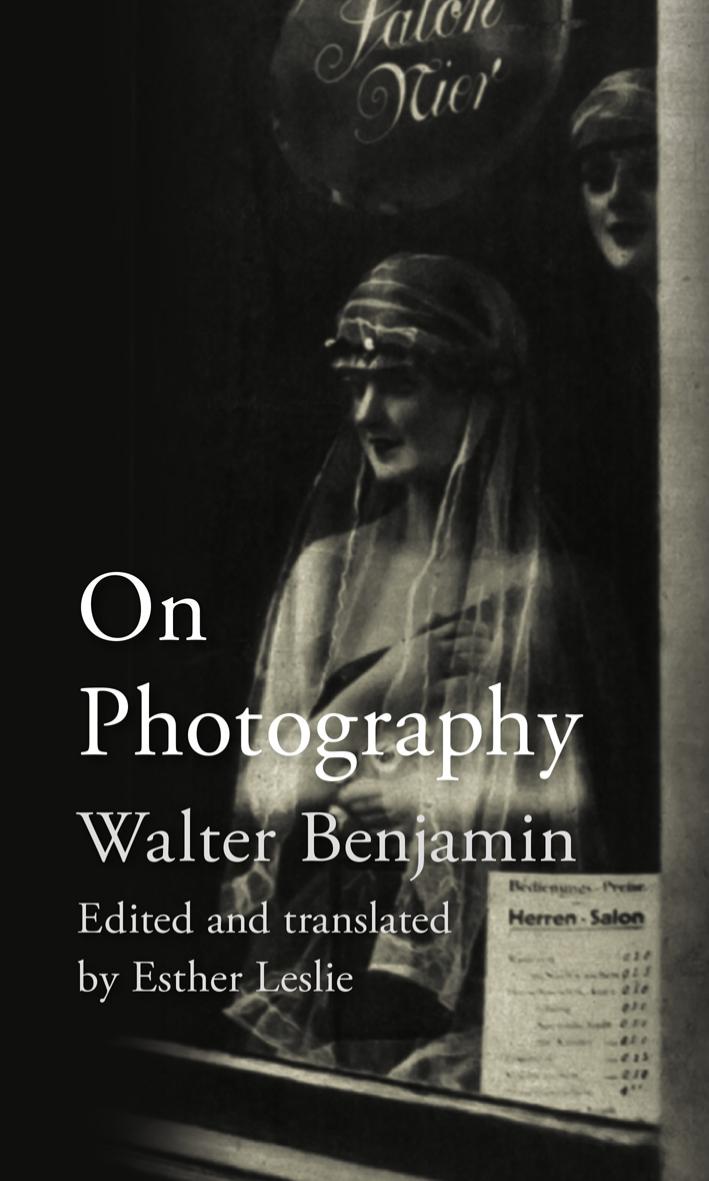

On Photography by Walter Benjamin

Author:Walter Benjamin

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: REAKTION BOOKS

Germaine Krull, Untitled, Paris, 1920s, from Benjamin’s personal collection.

Hippolyte Bayard (1801–1887), self-portrait.

Walter Benjamin as a child, wearing a Tyrolean suit, c. 1900.

Germaine Krull, Untitled, Paris, 1920s, from Benjamin’s personal collection.

Kafka as a child, 1888. This image was in Benjamin’s possession.

The image, with its boundless sadness, is a counterpart to those early photographs in which people did not yet gaze into the world as isolatedly and godforsakenly as does this lad here. There was an aura surrounding them, a medium that lent their gaze, which it suffused, fullness and certainty. And once again the technological equivalent is obvious; it obtains in the absolute continuum from the brightest light to the darkest shadows. Incidentally, this too provides evidence for the rule that later achievements are foreshadowed in earlier technologies, for old-style portrait painting was the spur for a sensational florescence of mezzotint engraving prior to its demise. Of course this process of mezzotint engraving is a technique of reproduction that combined only subsequently with the new photographic technologies. As in the sheets of mezzotint engravings, in Hill too the light wrests itself agonizingly from the darkness: Orlík speaks of the ‘generalized distribution of light’, resulting from the long exposure time, which lends ‘these early photographs their grandeur’. And among those who were contemporaries of the invention, Delaroche noticed the previously ‘unequalled and delectable’ overall impression, ‘in which nothing troubles the peace of the whole’. Enough on the technical conditioning of auratic appearance. Photographs of groups, in particular, still preserve an animated togetherness that appears for a short interval on the plate before perishing in the ‘print’. It is this circle of mist that is sometimes beautifully and suggestively transcribed in the now old-fashioned oval form of the excerpted image. It would be, therefore, a misreading of these incunables of photography to stress their ‘artistic perfection’ or their ‘tastefulness’. These images arose in spaces in which every customer encountered first of all a technician from the latest school, while the photographer saw in every customer a member of a class that found itself on the rise, possessing an aura that had lodged itself right into the folds of their bourgeois suit or their lavallière cravats. For this aura is certainly not a mere by-product of a primitive camera. Rather, in those early days, object and technology correspond just as precisely as they diverge in the following period of decline. That is to say, advanced optics soon had at its disposal instruments that could completely overcome the darkness and register appearances in a mirror-like fashion. However, photographers around 1880 saw their task to be much more to simulate the aura – which was then being banished from the image, given the supersession of darkness by more light-sensitive lenses, just as it was banished from reality by the increasing degeneration of an imperialist bourgeoisie. They saw it as their task to simulate this aura through practices of retouching, especially those of so-called gum printing. And thus, particularly in Art Nouveau, it became fashionable to have

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Ancient & Classical | Arthurian Romance |

| Beat Generation | Feminist |

| Gothic & Romantic | LGBT |

| Medieval | Modern |

| Modernism | Postmodernism |

| Renaissance | Shakespeare |

| Surrealism | Victorian |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11034)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(6836)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(5871)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(4718)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(4566)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4205)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(3982)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(3968)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3789)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(3705)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(3663)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(3578)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(3507)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(3430)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(3358)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3302)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3221)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3212)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3206)