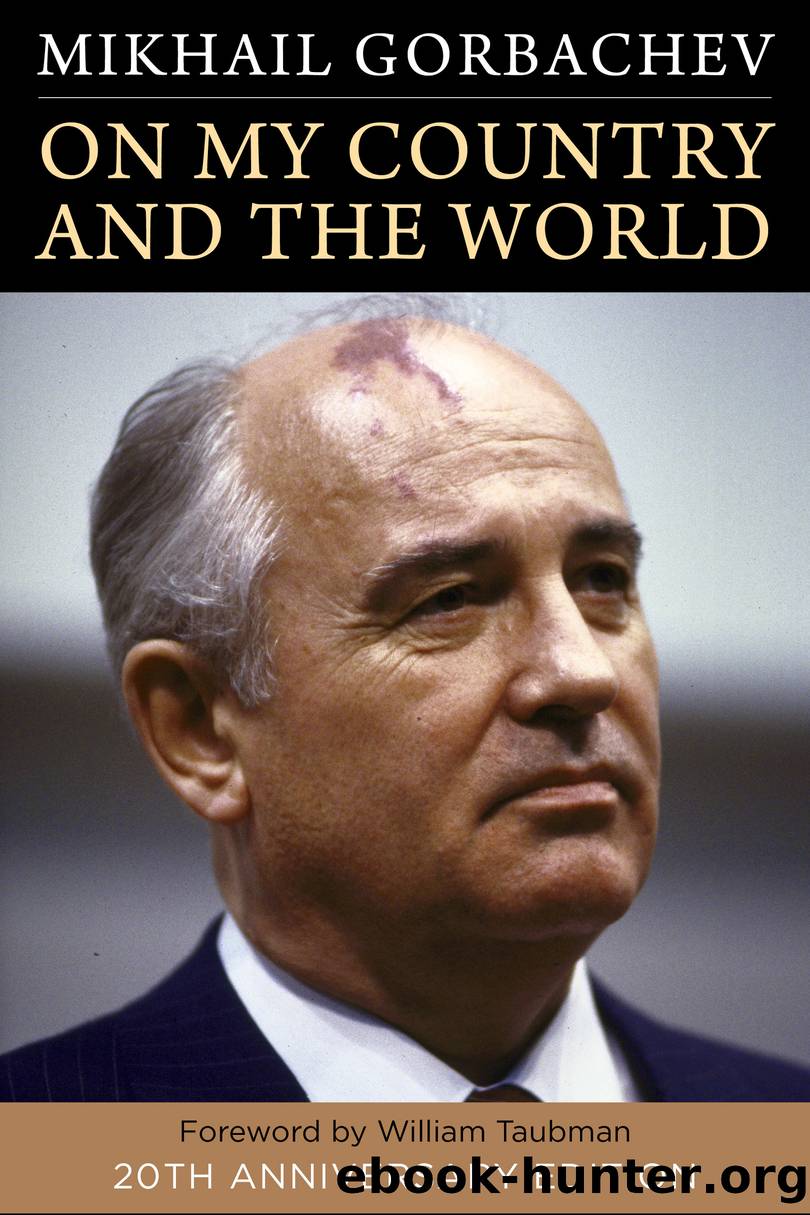

On My Country and the World by Mikhail Gorbachev

Author:Mikhail Gorbachev

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Columbia University Press

CHAPTER 15

What Lies Ahead?

Today, with the benefit of hindsight, I believe that those who signed the Belovezh accord had no intention, even from the outset, of carrying out the commitments they made. They deliberately deceived their own people because, after all, they clearly saw that they could win support only by appearing to be concerned about preserving the Union—granted in the form of a commonwealth. It had to appear that they were not retreating from the choice the citizens made in March 1991.

To deceive the public, to lead it astray in order to paralyze any possible resistance to the operation they had begun—that was their aim. It was as though they were saying: “Look, we are preserving everything that Gorbachev wants to preserve with his treaty, but in our version almost all the republics will unite except for the Baltic republics. Gorbachev’s version will unite only six, seven, maybe eight republics, leaving out Ukraine.”

In general—and I think this is obvious from everything I have said above—the Russian leaders, along with their two partners, intended to deceive the public from the very beginning. They proclaimed one thing to our country and to the international community, but they did another.

The commonwealth scheme lacked any real impulse toward cooperation. Today’s problems all flow from this. Of course, also sharing the blame are the politicians in the CIS countries. (I would exempt from this charge Nazarbaev, president of Kazakhstan, who insisted quite stubbornly, and still insists today, on the development of processes of integration.) The “top brass” in the CIS countries are happy playing the “sovereignty flute:” They do not wish to relinquish one iota of power. But unless they do, no kind of unification is possible. In short, the interests of the political elites were given priority over those of the citizenry.

Especially noteworthy is the responsibility of the Russian leadership in all this. By no means was it accidental that at a summit of the CIS, held in Kishinev in the fall of 1997, all the participants criticized Russia and its leadership for the Commonwealth’s state of paralysis. President Yeltsin even acknowledged that the criticism was justified: After all, for years he had been chairman of the Council of Heads of State, but during that time nothing ever moved from dead center. It is not yet clear what conclusions he has drawn (or will draw) from the sharp criticism lodged against him or from his own self-criticism. I, for one, do not expect much. True, recently there seem to have been some steps toward greater cooperation among members of the Commonwealth. Once the euphoria over independence had passed and sobriety had been restored, public opinion shifted significantly—and even the views of some of the political elite.

Under these conditions new attitudes have developed regarding the relations between members of the CIS—above all, those between Russia and the other member states. Here disparate interests clash and many different cards are being played—by Russia, the new states on the territory of the former USSR, their neighbors, Western Europe, and the United States.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Arms Control | Diplomacy |

| Security | Trades & Tariffs |

| Treaties | African |

| Asian | Australian & Oceanian |

| Canadian | Caribbean & Latin American |

| European | Middle Eastern |

| Russian & Former Soviet Union |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16611)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11486)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(7783)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(5755)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5032)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4818)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(4787)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4441)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(4413)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(4406)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4393)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4338)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4072)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4028)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4009)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(3876)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(3870)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3774)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3726)