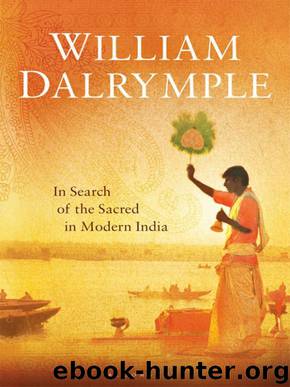

Nine Lives by William Dalrymple

Author:William Dalrymple [Dalrymple, William]

Format: epub, mobi

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

Published: 2009-10-23T16:00:00+00:00

Why call yourself a scholar, o mullah?

You are lost in words.

You keep on speaking nonsense,

Then you worship yourself.

Despite seeing God with your own eyes,

You dive into the dirt.

We Sufis have taken the flesh from the holy Quran,

While you dogs are fighting with each other.

Always tearing each other apart,

For the privilege of gnawing at the bones.

Lal Peri was not alone in her fears of the advance of the Wahhabis, and what this meant for Sufism in the region.

Islam in South Asia was changing, and even a shrine as popular and famous as that of Sehwan found itself in a position much like that of the great sculpted cathedrals and saints’ tombs of northern Europe 500 years ago, on the eve of the Reformation. As in sixteenth-century Europe, the reformers and puritans were on the rise, distrustful of music, images, festivals and the devotional superstitions of saints’ shrines. As in Reformation Europe, they looked to the text alone for authority, and recruited the bulk of their supporters from the newly literate urban middle class, who looked down on what they saw as the corrupt superstitions of the illiterate peasantry.

This had just been made especially clear only the previous week by the dynamiting of the shrine of the seventeenth-century Pashto poet-saint Rahman Baba, at the foot of the Khyber Pass in the North-West Frontier region of Pakistan. By chance, this was a shrine I knew very well. As a young journalist covering the Soviet–mujahedin conflict in the late 1980s from Peshawar, I used to visit the shrine on Thursday nights to watch Afghan refugee musicians sing songs to their saint by the light of the moon. For centuries, Rahman Baba’s shrine was a place where musicians and poets had gathered, and Rahman Baba’s Sufi verses in the Pashto language had long made him the national poet of the Pashtuns – in many ways the Shah Abdul Latif of the Frontier. Some of the most magical evenings I have ever had in South Asia were spent in the garden of the shrine, under the palms, listening to the sublime singing of the Afghan Sufis.

Then about ten years ago, a Saudi-funded Wahhabi madrasa was built at the end of the track leading to the dargah. Soon its students took it upon themselves to halt what they saw as the un-Islamic practices of the shrine. On my last visit there, in 2003, I talked about the situation with the shrine keeper, Tila Mohammed. He described how young Islamists now regularly came and complained that his shrine was a centre of idolatry, immorality and superstition. ‘My family have been singing here for generations,’ said Tila. ‘But now these Arab madrasa students come here and create trouble.’

‘What sort of trouble?’ I asked.

‘They tell us that what we do is wrong. They tell women not to come at all, and to stay at home. They ask people who are singing to stop. Sometimes arguments break out – even fist fights. This used to be a place where people came to get peace of mind.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

China Rich Girlfriend by Kwan Kevin(4551)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(4520)

Annapurna by Maurice Herzog(3460)

Full Circle by Michael Palin(3436)

Hot Thai Kitchen by Pailin Chongchitnant(3369)

Okonomiyaki: Japanese Comfort Food by Saito Yoshio(2705)

The Ogre by Doug Scott(2674)

City of Djinns: a year in Delhi by William Dalrymple(2543)

Photographic Guide to the Birds of Indonesia by Strange Morten;(2523)

Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos & Northern Thailand by Lonely Planet(2438)

Tokyo by Rob Goss(2423)

Tokyo Geek's Guide: Manga, Anime, Gaming, Cosplay, Toys, Idols & More - The Ultimate Guide to Japan's Otaku Culture by Simone Gianni(2357)

Everest the Cruel Way by Joe Tasker(2327)

Discover China Travel Guide by Lonely Planet(2207)

Iranian Rappers And Persian Porn by Maslin Jamie(2186)

China (Lonely Planet, 11th Edition)(2154)

China Travel Guide by Lonely Planet(2138)

Lonely Planet China(2136)

Top 10 Dubai and Abu Dhabi by DK Travel(2086)