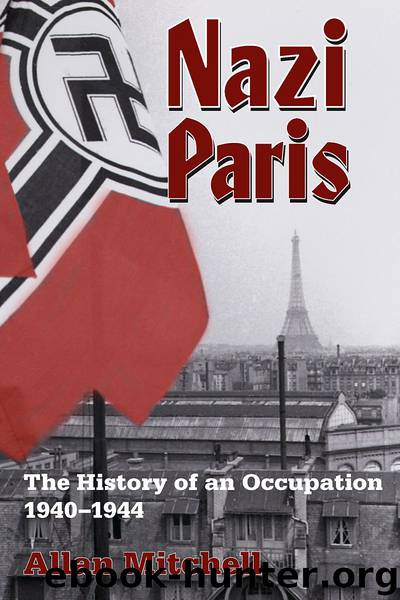

Nazi Paris: The History of an Occupation, 1940-1944 by Mitchell Allan

Author:Mitchell, Allan [Mitchell, Allan]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Berghahn Books

Published: 2015-10-21T16:00:00+00:00

Iron, ore, scrap metal 8,000,000 tons

Other metals and ores

Copper

240,580 tons

Aluminum

247,678 tons

Bauxite

679,080 tons

Machines

Locomotives

283 units

Freight cars

834 units

Automobiles

424 units

Trucks

31,340 units

Watches 66,000 monthly

Alarm clocks 200,000 monthly

Chemicals: soda 126,000 tons

Leather

Work shoes

3,180,000 pairs

Other shoes

5,210,000 pairs

Rubber 12,381 tons

Textiles 287,000 tons

Source: “Leistungen der französischen gewerblichen Wirtschaft für Deutschland,” 31 July 1943, AN Paris, AJ40, 779.

To these statistics must be added the “crucial importance” of French agricultural products for the Reich. For the year 1943, for instance, they included 1.4 million tons of grain, 270,000 tons of meat, 24,000 tons of butter, and 4,200,000 hectoliters of wine. By early 1944, according to the MBF's Economic Section, gathering reliable statistics on the chaotic French economy was “totally excluded.” Yet one of its staff reports included estimates that 65 percent of the French labor force was engaged in the German war effort, which was consuming 72 percent of France's total production and 93 percent of its industrial goods. However approximate they were, viewed by the Occupation these calculations certainly spoke of successful exploitation on a grand scale.27

The foregoing panorama of the French economy during 1943 and early 1944 provides the setting for a thick description of the most serious political crisis of the Occupation since the hostage issue erupted in August 1941. This primarily concerned demands by the insatiable Sauckel for a vastly increased recruitment of French labor for the Reich. The first “Sauckel Initiative” had limped to the finish line by the end of 1942, filling its quota of 250,000 workers to be transferred to Germany, of which 150,000 were classified as skilled, mostly in metallurgy.28 Supposedly, it was to be a one-time action. But even before January 1943, Sauckel disclosed plans for a second initiative, that is, the transfer of another 250,000 laborers in the first four months of the year. Complaints from the French, who naturally felt betrayed, as well as some negative rumbles within the MBF's own military administration about a likely reduction of French productivity, did not deter him. Flaunting telegrams of support from the Führer and from Albert Speer, Sauckel responded that recruitment would be curbed only if huge gaps might thereby be created in the French arms industry. Hitler's orders allowed no contradiction and “absolutely must be kept.”29 Reports from both the Commandant of Greater Paris and the Gestapo about the “significant unrest” in the French work force left Sauckel unruffled. Although labor recruitment was still legally voluntary, the German procedures actually resembled a labor draft. When, to Sauckel's annoyance, Vichy officials referred to these roundups as “deportation,” he dismissed his French critics as “procrastination artists” (Hinhaltekünstler).30

It is worthwhile here to eavesdrop on one of several personal confrontations between Sauckel and Laval at the Paris Embassy in the Rue de Lille. There, on 12 January 1943, Sauckel laid out the terms of the next recruitment effort: another 250,000 French workers were to be transferred to Germany, of which again 150,000 were to be skilled. The Relève would remain in effect at a ratio of one POW returned to France for every three skilled workers. They would need to move fast, however, by transporting 4,500 a day across the Rhine.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(10929)

The Templars by Dan Jones(4199)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4095)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4028)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3743)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(3531)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3467)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3450)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3096)

12 Strong by Doug Stanton(3065)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(2741)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(2655)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(2615)

The Art of War Visualized by Jessica Hagy(2424)

Hitler's Flying Saucers: A Guide to German Flying Discs of the Second World War by Stevens Henry(2306)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(2222)

The Second World Wars by Victor Davis Hanson(2140)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2079)

Tobruk by Peter Fitzsimons(2069)