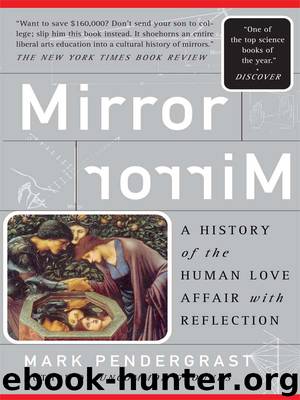

Mirror, Mirror by Mark Pendergrast

Author:Mark Pendergrast [MARK PENDERGRAST]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Basic Books

Published: 2011-01-01T00:00:00+00:00

Magic Mirrors Shine Again

Edward Crossley gave away his telescope because he had developed strong religious beliefs that soured him on trying to delve into the mysteries of the universe.* Once more, as in John Dee’s time, mirrors reflected conflicts between science and religion. In 1802, when William Herschel discussed the wonders of the heavens with Napoleon, the French leader interrupted to ask, “And who is the author of all this?” When Pierre-Simon Laplace tried to explain it all as a “chain of natural causes,” Napoleon objected. God must be given the credit, not evolution.

Following Charles Darwin’s 1859 publication of The Origin of Species, that argument became more heated, as science appeared to threaten traditional religion and values. In 1874, J. W. Draper, Henry’s father, published History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science, defending scientists against attacks by theologians. In the late Victorian era, as technological and scientific innovations produced unprecedented changes at a dizzying rate—steam engines, electricity, telegraphs, railroads—many people sought alternate forms of religious solace. Spiritualism, with its mediums, séances, and crystal balls, became popular. Scrying and magic mirrors enjoyed an extraordinary revival, even as rational scientific progress appeared triumphant.

John Melville’s Crystal Gazing and Clairvoyance, published in 1896, gave a pseudoscientific patina to scrying. “The crystal or mirror should frequently be magnetised by passes made with the right hand, for about five minutes at a time,” Melville explained, though he also thought that intense staring helped. “The Magnetism with which the surface of the mirror or crystal becomes charged, collects there from the eyes of the gazer, and from the universal ether, the Brain being as it were switched on to the Universe.”

David Brewster was fascinated by magic mirrors (including the Chinese variety), though he explained them scientifically. “If a fine transparent cloud of blue smoke is raised, by means of a chafing-dish, around the focus of a large concave mirror,” Brewster observed, “the image of any highly illuminated object will be depicted, in the middle of it, with great beauty. A skull concealed from the observer is sometimes used, to surprise the ignorant.”

Thus originated the phrase smoke and mirrors, as magic shows and theatrical effects thrilled Victorian audiences. Equipped with concave mirrors, lenses, and bright lime- or magnesium lights, magic lanterns projected “terrific heads [with] awful eyes and tremendous jaws” onto an invisible gauze screen; the images “then suddenly vanished,” as Eusebe Salverte wrote in his 1847 book, Philosophy of Magic, Prodigies, and Apparent Miracles.

In 1863, John Henry Pepper, the director of the Royal Polytechnic Institute in London, demonstrated an ingenious theatrical device in which live actors apparently interacted with ghosts on stage. The illusion, which relied on the beam-splitter qualities of glass, could be achieved through advances in plate-glass technology. A large sheet of glass was hung at a 45-degree angle with its foot near the front of the stage and its top extended toward the audience. With the stage lit and the audience in darkness, the glass was invisible. In a pit below the glass the “ghost” was hidden on an inclined platform.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Automotive | Engineering |

| Transportation |

Whiskies Galore by Ian Buxton(41967)

Introduction to Aircraft Design (Cambridge Aerospace Series) by John P. Fielding(33106)

Small Unmanned Fixed-wing Aircraft Design by Andrew J. Keane Andras Sobester James P. Scanlan & András Sóbester & James P. Scanlan(32779)

Craft Beer for the Homebrewer by Michael Agnew(18218)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(8002)

The Complete Stick Figure Physics Tutorials by Allen Sarah(7350)

Kaplan MCAT General Chemistry Review by Kaplan(6916)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(6909)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6601)

Modelling of Convective Heat and Mass Transfer in Rotating Flows by Igor V. Shevchuk(6421)

Learning SQL by Alan Beaulieu(6264)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6248)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(5981)

Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport;(5740)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5534)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5398)

Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion: Tesla, UFOs, and Classified Aerospace Technology by Ph.D. Paul A. Laviolette(5358)

Design of Trajectory Optimization Approach for Space Maneuver Vehicle Skip Entry Problems by Runqi Chai & Al Savvaris & Antonios Tsourdos & Senchun Chai(5055)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4984)