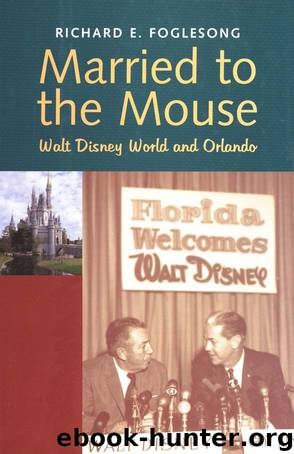

Married to the Mouse : Walt Disney World and Orlando by Richard E. Foglesong

Author:Richard E. Foglesong

Language: eng

Format: mobi

Published: 0101-01-01T00:00:00+00:00

SEVEN Abuse

O

n September 27, 1989, Sam Tabuchi flew with five of his advisers from Orlando to Tokyo for consultations the next day with Japanese investors regarding a train, predicted to reach 300 mph, that would run between Disney World and Orlando International Airport. The superfast train would ride on an electromagnetic cushion of air created by magnets on the train and track that repelled each other. This new technology was called “mag-lev,” combining magnetics and levitation. The train would not only save time for Disney-bound passengers, who could check their baggage through to their Disney hotel room, it would also remove thousands of cars and buses from the roads. For this, a consortium of Japanese investors, including Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank of Japan, the world’s largest bank, was prepared to invest up to $800 million.

Jane Hames, the Orlando public relations consultant who had previously advised the Disney Co. on dealing with Orange and Osceola counties, accompanied Tabuchi to Tokyo. Having arrived near midnight, she had just poured a cup of tea to soothe the jet lag when Tabuchi knocked at her hotel-room door. Looking devastated, he related the phone conversation he just had with Disney World president Dick Nunis.1 For months, Tabuchi, 37, had tried to get an answer from Nunis: was Disney willing to support the mag-lev train and allow a terminal on their property, near Epcot? “I need an answer, I need an answer,” Tabuchi had told the Disney executive. In particular, he needed an answer before flying to Japan to confer with his investors.2 Nunis had come through in part, leaving a message that awaited Tabuchi at his Tokyo hotel. Returning the call, Tabuchi heard the Disney World president say: “We can’t support the Epcot location, but we have another location in a cow pasture, three miles south of Epcot, where we’d agree to a terminal.”3

This was not the response that Tabuchi wanted to hear. He told Hames to assemble their group in the hotel restaurant, where they conferred until morning. The group included representatives from Mag-lev of Florida, the Tokyo-based company formed to promote the train project, and Transrapid International Corporation, a West German firm that would build the trains. At first light, Hames and the Japanese members of the group went to the slick, glass-walled offices of Akio Makiyama, the chairman of Mag-lev Transit, Inc., and one of Japan’s largest developers. As the investors met through the day, their Japanese was broken by the words “Nunis” and “Disney” and “cow pasture,” reported Hames.4

For Tabuchi, who worked four years to broker the Mag-lev deal, it was a tremendous loss of face. He had sold his investors on what they called a “Miss America idea,” an idea so good and pure it was bound to succeed. After all, they were solving a public transportation problem with private Japanese money, building a high-tech train that fit Epcot’s futuristic image, and exploiting Disney’s drawing power to showcase their train technology to millions of tourists. They had assembled tentative financing, secured land options, and passed legislation to expedite the permitting process.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16611)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11486)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(7783)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(5754)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5032)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4818)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(4786)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4441)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(4413)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(4406)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4393)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4338)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4072)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4027)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4009)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(3876)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(3870)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3774)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3726)