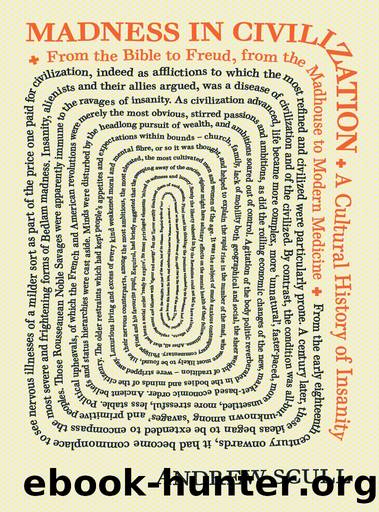

Madness in Civilization: A Cultural History of Insanity by Andrew Scull

Author:Andrew Scull [Scull, Andrew]

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Tags: Sociology, Psychology, Science, Mental Illness, Nonfiction, History

ISBN: 9780691166155

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Published: 2015-04-05T23:00:00+00:00

The staff at Hadamar, c. 1940â42, a psychiatric hospital used in the T-4 euthanasia programme, relaxed and happy after a hard day at work disposing of those the Nazis considered âunworthy of livingâ.

Chapter Nine

THE DEMI-FOUS

Avoiding the Asylum

The earliest profit-making madhouses had found their primary market among the rich and well-to-do. That should scarcely occasion surprise. In the immortal if possibly apocryphal words of the American bank robber Willie Sutton, that was where the money was. Still, it was a paradoxical state of affairs, for until the close of the nineteenth century and the advances associated with the invention of aseptic surgical techniques, the rich avoided hospital treatment for physical illness like the plague. It was the poor and those reduced to poverty who were treated in general hospitals, while the rich opted for treatment at home.

That abhorrence of the institution did not disappear when it came to the management of madness. Victorian letters, diaries and autobiographies are full of evidence that their authors feared asylums and had low expectations about the kinds of care their relations would receive in such places. Money could pay for alternatives, and there was considerable temptation to resort to them: building a cottage to confine an insane relative on a secluded portion of an aristocratic estate and hiring the necessary staff; placing the disturbed in single lodgings (St Johnâs Wood in London became a favourite place for such establishments, having the extra advantage of easy access to the advice of discreet society physicians â its reputation as a haven for such illicit confinement was exploited by Wilkie Collins in his novel, The Woman in White, 1859);1 or patients could simply be sent abroad, beyond the reach of prying official eyes and to places that provided some additional protection against the possibility of gossip, scandal and stigma.2 French and Swiss asylums, for example, advertised openly in London and Paris in an effort to attract such custom.

Perhaps the most striking example of the resort to such expedients is provided by the case of Anthony Ashley Cooper, from 1851 the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. Shaftesbury served as chairman of the English Lunacy Commission from its founding in 1845 until his death in 1885, and in that capacity promoted the asylum as the sole appropriate response to cases of insanity. Testifying before a parliamentary enquiry in 1859 into the operation of the English lunacy laws, he observed that, were his wife or daughter to become mentally deranged, he would at once arrange for her admission to a modern asylum, which provided the best possible environment for humane care and cure. His choice of relations was perhaps deliberate, because his behaviour did not match his public proclamations. His third son, Maurice, was epileptic and mentally disturbed. Despite his lifelong and vociferous opposition to the practice, Shaftesbury had him secretly and privately confined, and when there was a prospect that this situation might become public, he sent him abroad to confinement, first in the Netherlands and latterly in Lausanne, Switzerland, where the poor young man subsequently died in 1855, aged just twenty.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Leavers by Lisa Ko(6468)

Born to Run: by Christopher McDougall(6258)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(4702)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(4534)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(4429)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(4195)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(3178)

Livewired by David Eagleman(3121)

Goodbye Paradise(2957)

Never by Ken Follett(2877)

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(2516)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(2416)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2356)

People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory by Dr. Brian Fagan & Nadia Durrani(2346)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(2308)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2281)

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (5) by J.K. Rowling(2226)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2218)

Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes by Daniel L. Everett(2216)