Living Sharia by unknow

Author:unknow

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Nonfiction, History, Asian, Southeast Asia, Religion & Spirituality, Middle East Religions, Islam, Social & Cultural Studies, Social Science, Anthropology

ISBN: 9780295742564

Publisher: University of Washington Press

Published: 2017-11-16T05:00:00+00:00

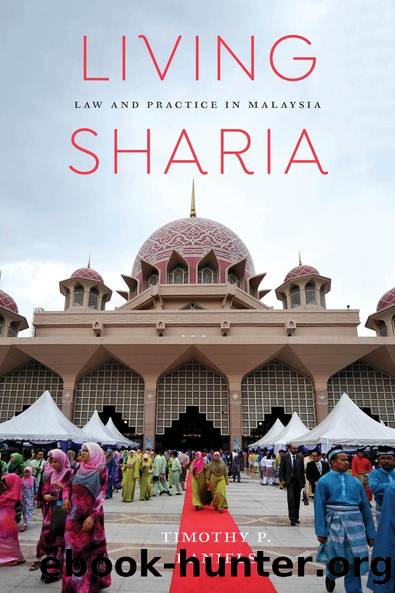

Friday morning religious instruction, Kota Bharu, Kelantan

My local interlocutors often referred to the widely adored Kelantan chief minister Tuan Guru Nik Aziz as an example of âproperâ Islamic consumption (cf. Fischer 2008). Despite having been chief minister for twenty years, he still lived in the same kampong house he did before taking office. His long-term residence in a kampong house, a popular symbol evoking continuity with the Malay rural past, casts him as a common man rather than part of the âNew Malayâ elite (see Thompson 2007, 177, 183). They also proudly note that he still wears baju melayu (traditional Malay Muslim attire) with a turban like he did years ago, in stark contrast to the exquisite business suits and dress shirts of UMNO leaders. The Kelantan state governmentâs âDeveloping with Islamâ project, âanti-sinful-activitiesâ campaign, and exemplary consumption practices remind and motivate people to live according to the straight path predicated on sharia rules and principles. Furthermore, the public absence of maksiat, such as alcohol consumption, prostitution, and gambling, and the simple, corruption-free lifestyle of the Kelantan chief minister, are embodied practices and symbols of the Islamic path to salvation.18

Interest-free banking was a national Muslim concern prior to the PAS electoral victory in 1990. Malaysian Muslim scholars shared a consensus that paying or receiving interest was prohibited according to sharia. The UMNO-led federal government had already embraced interest-free banking as part of its Islamization program establishing Malaysiaâs first Islamic bank, the Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad, in 1983. Nevertheless, PAS, galvanized by the UMI notions, propelled a further Islamization of banking institutions. State leaders in the early 1990s refused to store government funds in banks without interest-free counters, eventually spurring most banks to offer such services. They also established programs offering interest-free loans to civil servants and students, embodying their ethical cultural schema.

Furthermore, PAS, unlike UMNO-BN, established the principle of separating state funds into halal (permitted) and non-halal accounts based on their sources. If funds originated from interest, gambling, or alcohol, for instance, they were separated from funds made via âmorally cleanâ sources (halal), such as agriculture and trade in permitted products. In 1991 the state government established an innovative fund called Tabung Serambi Mekah (TSM), which included money from halal and haram (forbidden) sources held in separate accounts and used for different purposes. PAS ulama explained that this fund provides an opportunity for people with money from haram sources to put it to good use in support of public works. According to the deputy chief ministerâs records, only halal funds were distributed to needy segments of the populationâthe poor and victims of natural disastersâwhereas funds from haram sources were used for infrastructural projects or building non-Muslim religious institutions. These policies not only relieved pious Muslim fears that their halal money was being mixed with haram money but reaffirmed that untarnished good was being done with it through distribution to poor and needy Muslims. Arguing that this was the proper separation and allocation of these funds, PAS leaders enacted their ethical cultural schema and its extension through UMI.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16706)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11502)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(7824)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(5819)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5068)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4858)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(4806)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4470)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(4457)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4439)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(4434)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4364)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4103)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4051)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4037)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(3908)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(3890)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3800)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3748)