Ku-Klux by Elaine Frantz Parsons

Author:Elaine Frantz Parsons

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2015-12-15T00:00:00+00:00

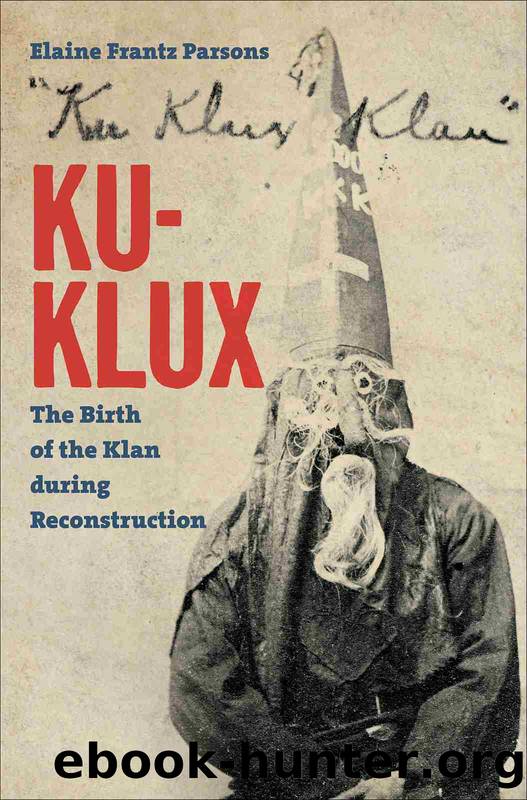

The Library of Congress identifies the men pictured here as members of the Watertown, New York, Division 289 of the Ku-Klux Klan, c. 1870. Marian S. Carson Collection, Library of Congress.

With Ku-Klux deliberately introducing comic elements into their acts of violence and the widespread practice of reducing the Ku-Klux to a comic parody, readers may well have approached reports of Ku-Klux violence with an expectation of comic exaggeration.75 For instance, when the Little Rock Morning Republican quoted the (Republican) Memphis Postâs claim that Ku-Klux âhave evidently learned their language in the school of the Black Crook,â a contemporary hit burlesque production, neither paper may have desired to trivialize violence against freedpeople.76 Yet when a Savannah Democratic paper, the Daily News and Herald, similarly analogized the Ku-Klux to the Black Crook a few days later, it easily took the logic further, calling the Klan as a whole âa capital jokeâa âsell.âââ77 Similarly, when a piece of seemingly incontrovertible evidence of the existence of the Ku-Klux emerged, it could be neutralized by translation into farce. Days after the Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.) reported that a costumed Ku-Klux had been killed by his would-be victim, it clarified it had all been a tragic misunderstanding. According to this follow-up story, a young white man, probably inspired by his belief in âthe universal terror of blacksâ (that is, black peopleâs âconstitutional timidityâ), had decided to scare a black man by donning a mask and sheet, approaching his house at night, and threatening to kill everyone in it. Unfortunately for the prankster, the freedman he targeted had not known that this was a joke.78 Similarly, when three congressmen claimed to have received Ku-Klux threats during the impeachment hearings, Democrats dismissed it as a âhoaxâ or even an April Foolsâ Day joke.79 Southern humorist Brick Pomeroy published a book in 1871 in which a worthless northern man headed south, acted obnoxious there (âPlowinâ, are ye?â Why ainât ye in a grocery, hurrahinâ for Grant? Is this the way you spit upon your benefactors!â), and then accused those who gave him a quite reasonable âbouncingâ of being Ku-Klux.80 It was common for newspapers to write about racial violence using sensationalist or minstrelesque tropes (the bullet âpassed near the head of a âschool marmâ present, who is said to have jumped over three benches at one jump in her excitementâ).81 It was difficult for contemporaries to locate the âsolid realityâ beneath the Klanâs âstuff and nonsense.â82

Framing Ku-Klux violence in a sensationalist mode worked in much the same way as framing it in the comic mode. Like comedy, sensationalism worked by presenting accounts of Ku-Klux violence so grotesque and exaggerated that it was impossible to take them seriously. Sensationalist writing was intended to evoke horror or fear rather than laughter, yet the two were often so entangled as to be indistinguishable from one another. The Tribune article âHorrible Disclosuresâ was a comic parody of sensationalist writing: it lampooned Stalwart accusations against Greeley during the campaign, confessing that Greeley âcommitted Ku-klux outrages in nearly all the southern States.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| General | Discrimination & Racism |

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7690)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5431)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5408)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4565)

The Sports Rules Book by Human Kinetics(4379)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(4375)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4242)

Captivate by Vanessa Van Edwards(3838)

Mummy Knew by Lisa James(3686)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3536)

The Worm at the Core by Sheldon Solomon(3485)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3460)

The 48 laws of power by Robert Greene & Joost Elffers(3240)

Suicide: A Study in Sociology by Emile Durkheim(3017)

The Slow Fix: Solve Problems, Work Smarter, and Live Better In a World Addicted to Speed by Carl Honore(3006)

The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell(2911)

Humans of New York by Brandon Stanton(2865)

Handbook of Forensic Sociology and Psychology by Stephen J. Morewitz & Mark L. Goldstein(2692)

The Happy Hooker by Xaviera Hollander(2686)