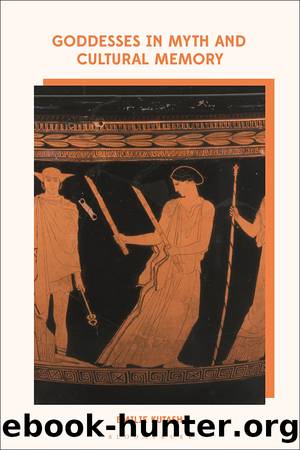

Goddesses in Myth and Cultural Memory by Emilie Kutash;

Author:Emilie Kutash;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Bloomsbury UK

8

Asherah, Sophia, Shekhinah: Are They Hebrew Goddesses?

Rabbi Leah Novickâs book On the Wings of the Shekhinah: Judaismâs Divine Feminine is an example of the fact that the female presence that appeared in Kabbalist literature, the Shekhinah, has been appropriated by some contemporary devotional practices and imagination. The living nature of this experience is encapsulated in her opening statement:

Wandering along the California coastline six years ago, I began to experience the Divine Feminine in the hills, the ocean and the landscape. A gigantic goddess was calling to me. (p. 1)1

Apparently Rabbi Novick has reactivated, perhaps metaphorically, a feminine principle and renders it as an active presence in her spiritual life. For many of those who follow this approach, the so-called divine feminine is associated with the Shekhinah. The beauty of nature prompts Novick to characterize the common aesthetic/spiritual experience of the awe one can experience in nature as an instance of gender-specific divinized presence. While Artemis is the Greek ancestress of the contemporary divine feminine that is experienced in nature, in this book, written by a rabbi, what is conflated with nature and her internal epiphany is primarily the Hebrew precursor to her divinization of nature: the Shekhinah. The age-old association of the female divinized or not, with nature, never seems to go away, either in Jerusalem or in Athens. From the possibilities suggested by female goddess figurines and inscriptions discovered in ancient Israel to allusions to female goddesses in the Prophets, to the Shekhinah imagery in the medieval Kabbalah, although female deity is not part of mainstream Hebrew doctrine, these instances encourage speculation about this issue. In addition to amending gender biases in traditional liturgy, modern scholars have taken renewed interest in the question of whether there was ever a Hebrew goddess. Furthermore, the âShekinahâ construed as a female presence within divinity has taken on new significance in some contemporary settings.

Rafael Patai, a cultural anthropologist, has taken a studied interest in this question. As he puts it: âNo subsequent teaching about the aphysical , incomprehensible, or transcendental nature of the deity could eradicate the early mental image of the masculine god.â2 The very nature of most languages accounts for much of the genderizing of words and names. The descriptions, âKing,â âMaster of the Universe,â âfather,â expressions common in Talmudic literature, persist in contemporary liturgy. While none of these expressions are indicative of any doctrine concerning the masculinity of God, metaphorically, the dependence on God on the part of the Jewish people is generally stated as that of a child on a father. Is there any historical precedent for amending this practice? There is plausible evidence that in certain isolated instances, such as that of the Elephantine Jews (c. fifth century BCE), some sort of female consort of Yahweh (the Hebrew God) was worshipped. In biblical literature, particularly in the books of the Prophets, the worship of a female âgoddessâ is railed against and considered idolatrous. This is both proof that such a figure was worshiped in some ancient practices and an indication that it was not condoned.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Born to Run: by Christopher McDougall(7128)

The Leavers by Lisa Ko(6948)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5417)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5372)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5197)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5181)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4313)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4192)

Never by Ken Follett(3957)

Goodbye Paradise(3811)

Livewired by David Eagleman(3775)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3399)

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(3085)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3074)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3031)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2926)

Will by Will Smith(2920)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2846)

People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory by Dr. Brian Fagan & Nadia Durrani(2739)