Environmental Politics and Policy in Aotearoa New Zealand by Julie L MacArthur

Author:Julie L MacArthur

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Auckland University Press

Published: 2022-01-15T00:00:00+00:00

10

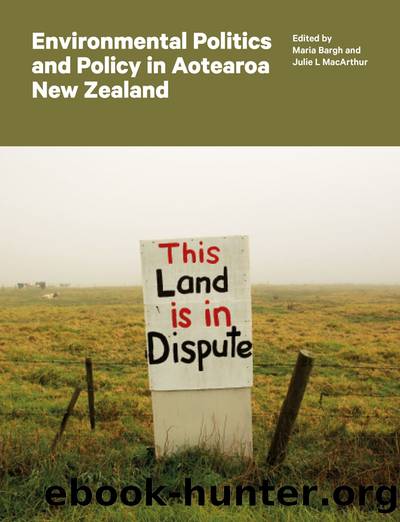

Social Movements and the Environment

Priya Kurian, Raven Cretney, Debashish Munshi and Sandra L. Morrison

Introduction

Concern for environmental conservation in some form in Aotearoa New Zealand â as elsewhere in the West â can be formally traced back to at least the mid-nineteenth century (Young, 2004), although this was preceded by Indigenous values and practices around the use of natural resources (Gunn, 2007; Young, 2004). Legislation to protect forests and wilderness emerged in New Zealand around the 1870s, followed by the Scenery Preservation Act of 1903. This led to the compulsory acquisition of land to create scenic reserves, much of which land was owned by MÄori, who were poorly compensated for their loss (Mills, 2009). At the same time, the dominant discourse of settler colonialism revolved around âproductiveâ land use, which saw large-scale deforestation, destruction of biodiversity and the draining of wetlands, and remained largely unquestioned by either the state or a majority of PÄkehÄ society at large (Skilling et al., forthcoming). Thus both âconservationismâ and âpreservationismâ â the forerunners of the modern environmental movement â did little to challenge the large-scale environmental change unfolding across the country, while remaining impervious to MÄori rights and concerns.

It took until the second half of the twentieth century for a raft of social movements, including environmental movements, to emerge across the West, paralleled by environmental struggles launched by the poor and dispossessed in many parts of the Global South (Guha, 2000; Guha & Martinez-Alier, 1997). The turbulent decades of the 1960s and 1970s saw the mobilisation of people protesting about a range of issues, including air and water pollution, control over land, deforestation, the construction of dams and so on. Since then, new waves of environmental activism have burgeoned globally, embodied by the presence of thousands of non-governmental and social movement organisations (Doyle, 2005; Rootes & Brulle, 2013), driven not only by a sense of anger and justice but also by a desire to raise awareness, shift political decision-making processes and bring about a transformation in cultural values and norms (Martin, 2015).

Examination of the cultural and ideological underpinnings of environmental destruction also includes unmasking the masculine worldview of âprogressâ and âdevelopmentâ that hides the human domination and exploitation of nature (see, for example, Kurian, 2019; Kurian & Munshi, 2016; MacGregor, 2019; Merchant, 1980; Plumwood, 1996). A âgender lensâ offered by feminist environmental scholarship (Arora-Jonsson, 2014; Kurian, 2019; MacGregor, 2019) allows us to see how capitalism and colonialism â directly implicated in the creation of the ecological crisis, the genocide of Indigenous peoples and the exploitation of women and marginalised groups â are imbued with a masculinist ideology (see, for example, Ghosh, 2016; Klein, 2014; MacGregor, 2019; Whyte, 2014). It also allows us to examine how social movements, too, are gendered â in terms of who participates and in what capacity, what strategies are used and to what effect.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, environmental concern has grown substantially in recent years. Water quality, climate change, waste and loss of biodiversity are all issues that New Zealanders are

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19053)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12187)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8894)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6877)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6267)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5787)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5737)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5500)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5431)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5216)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5144)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5081)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4954)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4921)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4780)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4741)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4709)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4502)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4484)