Disaster Drawn by Hillary L. Chute

Author:Hillary L. Chute

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780674504516

Publisher: Harvard University Press

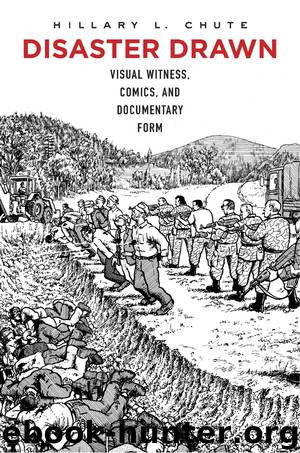

Figure 4.12 Art Spiegelman, The Complete Maus, page 231. (From The Complete Maus: A Survivor’s Tale by Art Spiegelman, Maus, Volume I copyright © 1973, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986 by Art Spiegelman; Maus, Volume II copyright © 1986, 1989, 1990, 1991 by Art Spiegelman. Used by permission of the Wylie Agency LLC and Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.)

Spiegelman’s inked lines materializing Vladek’s “deposition,” a performative, cross-discursive collaboration that goes inside the camps, portrays death in word and image. As a richly visual work, and one invested in its ability to show, Maus refutes on many levels the anti-imagism in discourse about the Holocaust, described recently in Georges Didi-Huberman’s incisive Images in Spite of All. Didi-Huberman uses his discussion of four rare photographs smuggled out of Auschwitz by prisoners in 1944 to refute theorists and filmmakers attached to a thesis of the unimaginable, the aesthetics of “showing absence.”89 Among the four photographs Didi-Huberman analyzes, all secretly taken by the same inmate within the space of about ten minutes, is one that Spiegelman draws in Maus. It appears on the page directly after the double spread of the crematorium: an image of Hungarian Jews, outdoors, being dragged and thrown into burning pits in August 1944. The image appears with a jagged border, indicating its difference from the other framed images on the page; it sticks out slightly into the horizontal gutter, as if laid on the space of the grid instead of created within it. A Sonderkommando stands in a heap of dozens upon dozens of bodies laid out on the ground, grabbing the limbs of one and balancing his own body weight with an outstretched arm in order to throw it into an open-air incineration pit from which smoke thickly rises in front of him. “Train after train of Hungarians came,” Vladek explains, and above the drawing, whose quavery border marks its status as a separate kind of frame, “And those what finished in the gas chambers before they got pushed in these graves, it was the lucky ones” (page 232).

Maus is interested in documenting as the texture of visual articulation, however supposedly direct, mediated, or re-mediated. Spiegelman not only incorporates Kościelniak’s camp-commissioned louse poster as a reference but reactivates it to perform the work of witnessing (of daily camp life) as part of the visual stuff of Maus. In much the same way, the clandestine photograph of the bodies being dragged into the pits—taken by a Greek Jew known only as Alex—becomes part of the book’s testimonial visual surface (page 232; Figure 4.13). If Spiegelman was inspired by the postwar pamphlets and by inmate drawings for their urgent transmission of visual information, Maus also relies on hard-to-find photographic documentation—here, on the “chilling out-of-focus snapshot” that bears urgent witness.90 But instead of adding the photograph to the book, as with the three family photographs that appear across Maus’s pages (unlike anywhere in Nakazawa

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11033)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(6836)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(5870)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(4718)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(4566)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4205)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(3982)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(3968)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3789)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(3705)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(3663)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(3578)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(3505)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(3430)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(3358)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3302)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3220)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3212)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3206)