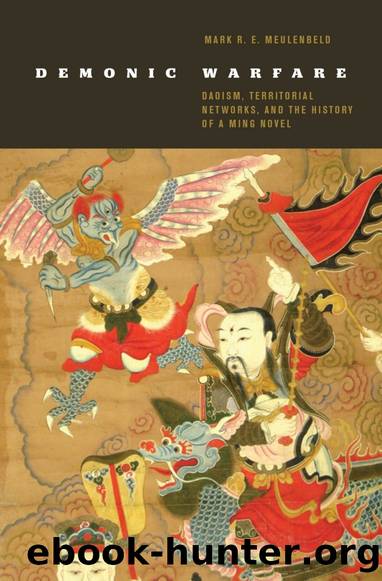

Demonic Warfare: Daoism, Territorial Networks, and the History of a Ming Novel by Mark R.E. Meulenbeld

Author:Mark R.E. Meulenbeld [Meulenbeld, Mark R.E.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780824838447

Google: rB_HDwAAQBAJ

Amazon: 0824838440

Barnesnoble: 0824838440

Goodreads: 25264631

Published: 2017-05-07T13:46:01+00:00

Demonic Warfare during the Yuan

125

It is thanks to the fi nal ban on dramatic per for mances that a substantial basis for further analysis is provided. Th

is last ban, applied to Jiangnan, comes in

1336 and refers to a genre I explored in chapter 2, namely the âPlain Tale.â

Th

is reference limits the range of (known) stories to such narratives as the Plain Tale of King Wuâs Conquest of King Zhòu or the Plain Tale of the Th ree

Kingdoms. Interestingly, the ban addresses the most basic form of military self- strengthening on the local level: the use of metal pitchforks by rural folk in the south. Th

e law is designed âin order to prevent [southerners] from staging rebellions.â109 It is in this context of war and rebellion that the ban furthermore specifi cally prohibits three performative genres of the kind discussed earlier: âtheatre scriptsâ ( xiwen), âvariety theatreâ ( zaju), and, most signifi cantly, the âPlain Tale.â Remarkably, less than fi fteen years after the publication of those Plain Tales that include King Wuâs Conquest and Th ree Kingdoms, the Yuan fi nd it a narrative genre that needs to be declared illegal.

Much of it must have had to do with its content.

Th

e Plain Tale of King Wuâs Conquest of King Zhòu features a protagonist, Yin Jiao, who is part of Daoist exorcist ritual in the region of Huguang, as well as part of local exorcist networks in the Hangzhou region. We know that very generally speaking, Yin Jiaoâs Plain Tale explains ways in which armies may be or ga nized on the basis of cosmological principles that correspond to the scheme of the Five Quarters. Th

e armies in question, moreover, consist of

plague gods or spirits that are known from Daoist liturgies of the period preceding the publication of the Plain Tales. Demonic warfare looms large.

Th

e other âPlain Tale,â Th ree Kingdoms, similarly relates to the notion of supernatural powers that may assist the living at times they are threatened by alien invasions. Even more concretely than the narrative of King Wu, the Plain Tale of the Th

ree Kingdoms contains specifi c references to militias such as the âRigh teous Troopsâ ( yibing) and âRigh teous Armiesâ ( yijun)â terms that clearly do not belong to the time in which the story is set, the aftermath of the Han collapse. Th

ey clearly correspond to the parlance generally used for the militias of the territorial cult during the early fourteenth century.

It is possible to be more specifi c: what the Plain Tale of the Th ree Kingdoms is written to convey, among other things, is the claim that these local militia are supervised by godsâ in the fi rst place Guan Yu, then Zhang Fei, and Liu Bei. Th

e foundation of their three kingdoms (another story of spatial conquest and dynastic establishment) is premised on the presence of Daoist divinities: Emperor Guangwu is said to be the Great Emperor of the Purple Tenuity (Ziwei Dadi), and the Jade Emperor is another point of reference early on in the story.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12377)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7757)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7330)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5761)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5756)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5415)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5082)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4935)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4723)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4566)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4548)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4526)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4439)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4098)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4023)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(4006)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3996)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3976)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3844)