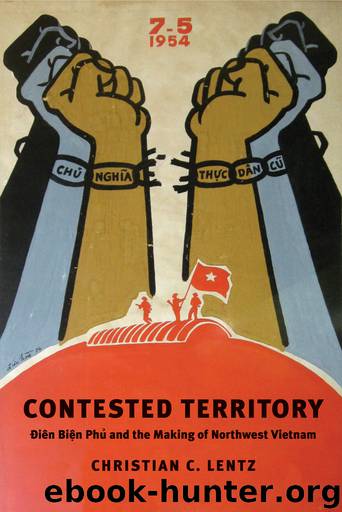

Contested Territory by Christian C. Lentz;

Author:Christian C. Lentz; [Lentz, Christian C.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2018-03-08T16:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER 5

Struggles at Điện Biên Phủ

THE LIVED EXPERIENCE OF LOGISTICS built tensions into Vietnamese territory. During early stages of the Điện Biên Phủ Campaign in late 1953, a DRV political cadre reported “increasing tensions” and “many anxieties” and “worries about production” among the people from Yên Bái and Sơn La working on Road 13. After the new road’s completion, the central government issued another order to “guarantee traffic flows,” requiring a “large number” of workers to return to the construction site all over again. Each wave of labor mobilization followed on the one previous, the cadre wrote, such that many dân công had time neither to rest and recover nor to harvest the last rice crop, plant the next one, and pay the agricultural tax. As a result, “all” of the approximately three thousand farmers turned workers were “anxious” (thắc mắc), a term that indicated political relations as much as affect. The political cadre forwarded complaints from two groups. “The Government liberated places where we built roads, but when we went home to increase production,” one group said, “we had to depart again immediately, leaving nothing to eat.” Another group argued, “The agricultural tax is heavy but, because we’re not at home to increase production, there’s nothing left to take for contributions.”1

Months if not years of heavy logistics labor was extracting a human toll and exposing contradictions from militarization of the Black River region’s agrarian economy. Even before the latest push, as of October 1953 and from Sơn La alone, some fourteen thousand Tai (Thái), Mường, Hmong (Mèo), Dao, Tày (Thổ), and Kinh (Việt) people had worked 840,000 workdays, or an average of two months per person, to blaze Road 13. Now, moving earth, making gravel, cutting wood, and cooking camp food added to their exhaustion and kept them from tending home and field. Even the specialists and political cadres who watched over them now clamored for “rest” and to see their families again. Even as these cadres carried out the central government’s orders, however, they had “not followed correct policy” aiming to ensure “equitable and fair” service. In practice, dân công service spared the rich and fell heavily on poor and vulnerable people. Recruiting “by rooftop,” or on a household basis, yielded many children, the elderly and infirm, and women in the second trimester of pregnancy. Some villagers hid from recruiters while others, back on site, tried to escape or wept openly, begging to go home.2 Not only had transportation trumped provisions, fulfilling one item at the expense of another on the DRV state’s logistics agenda, the state itself was showing deep strains at its territorial interface, exposing a gap between central ideals and priorities on the one hand and local realities and consequences on the other.

Conditions on the Road 13 site indicate broader, more intimate tensions caused by the work of constructing Vietnamese territory in the Black River region at a pivotal moment. Whereas the last chapter emphasized institutional development and elite decision making in the Điện Biên Phủ Campaign, this chapter tells the campaign’s story from the bottom up.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Craft Beer for the Homebrewer by Michael Agnew(18218)

Marijuana Grower's Handbook by Ed Rosenthal(3661)

Barkskins by Annie Proulx(3347)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(3207)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2915)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2910)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2833)

Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation by Tradd Cotter(2679)

In the Woods by Tana French(2576)

Beer is proof God loves us by Charles W. Bamforth(2434)

7-14 Days by Noah Waters(2400)

Borders by unknow(2297)

Between Two Fires by Christopher Buehlman(2283)

Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor(2282)

Meathooked by Marta Zaraska(2251)

The Art of Making Gelato by Morgan Morano(2243)

Birds, Beasts and Relatives by Gerald Durrell(2202)

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change (25th Anniversary Edition) by Covey Stephen R(2180)

The Lean Farm Guide to Growing Vegetables: More In-Depth Lean Techniques for Efficient Organic Production by Ben Hartman(2122)