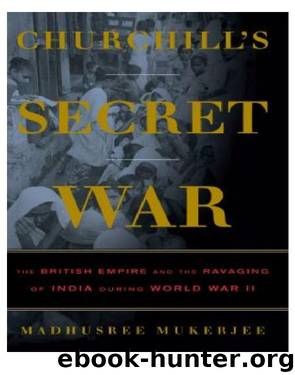

Churchill's Secret War by Madhusree Mukerjee

Author:Madhusree Mukerjee

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

Publisher: Basic Books

Published: 2010-07-13T16:00:00+00:00

“AFTER THE FLOOD we started a vegetable garden,” said Chitto Samonto. His family owned less than a half-acre of land, but because many of the local people had died or wandered away, fields all around now lay fallow. There the brothers sowed pumpkins, squash, and watermelons. In three months they started to get fruit, which they boiled and ate, long before it could ripen. “Otherwise we had coconuts and some boiled kolai,” he said. These lentils, which when freshly picked resemble tiny green peas, are a valuable source of protein but contain few calories. “We would gulp everything down with water,” Samonto remembered. They also boiled and ate stems of yam, fleshy stems of vine, leaves and seeds of tamarind and other trees, seeds of grass, and stringy whole kolai plants, which were normally fed to cows. Occasionally they drank palm sugar mixed with water. Finding and processing food often took more energy than one could get out of eating it.

For much of that time the family had an extra mouth to feed. Chitto’s elder sister was married to a postal officer in Calcutta. But after her ten-year-old daughter had died of some illness, her husband had taken to abusing her, so her father had brought her back to Kalikakundu. Many of the poor were selling their land jawler damey—as cheap as water—in order to buy rice, so the husband then bought almost twenty acres in a village not far away. He carried a badge that kept him safe from the police, and he would sometimes visit his estranged wife. “He praised the British all the time, said they were civilized,” recalled Samonto. “One time he was coming along the fields to our house, cursing Gandhi loudly. Our boys from the underground government”—here Samonto grinned—“caught him and took away his watch, ring, and bicycle.” Chitto’s father recovered the valuables and sent them back to his son-in-law, who never ventured that way again. Near the end of the famine the sister was fortunate to get a nurse’s job in a faraway town.

“My mother wouldn’t eat—she would feed us,” Samonto recalled. “Still, we were like skeletons. Sometimes I would just sit around and cry.” About five months after the flood a gruel kitchen opened in a neighboring village, but its soup “wouldn’t fill your belly.” Later some relief materials were distributed at Geokhali, eight miles away, and Chitto and his brother trekked there to collect it. “Some days it would take me two and a half hours to get there, I was so weak. They gave us rice, half rotted and with worms inside—it had been sitting around in a storehouse. The two of us brothers would come back with five kilograms for a week. But there were four of us in the house, it wasn’t enough.” In normal times a youth such as Chitto, who worked in the fields, would eat a kilogram of rice a day.

One night in the rainy season, the police surrounded their house. Chitto and his brother

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany by William L. Shirer(1214)

Flight by Elephant(1152)

German submarine U-1105 'Black Panther' by Aaron Stephan Hamilton(890)

Last Hope Island by Lynne Olson(806)

Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption by Hillenbrand Laura(782)

The Victors - Eisenhower and His Boys The Men of World War II by Stephen E. Ambrose(771)

0060740124.(F4) by Robert W. Walker(766)

The Guns at Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 1944-1945 by Rick Atkinson(746)

A Bridge Too Far by Cornelius Ryan(736)

War by Unknown(733)

The Hitler Options: Alternate Decisions of World War II by Kenneth Macksey(731)

The Railway Man by Eric Lomax(710)

All the Gallant Men by Donald Stratton(693)

Hitler's Armies by Chris McNab(678)

Rogue Heroes: The History of the SAS, Britain's Secret Special Forces Unit That Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War by Ben Macintyre(678)

Churchill's Secret War by Madhusree Mukerjee(674)

Hitler's Vikings by Jonathan Trigg(670)

A Tragedy of Democracy by Greg Robinson(648)

We Die Alone: A WWII Epic of Escape and Endurance by David Howarth & Stephen E. Ambrose(643)