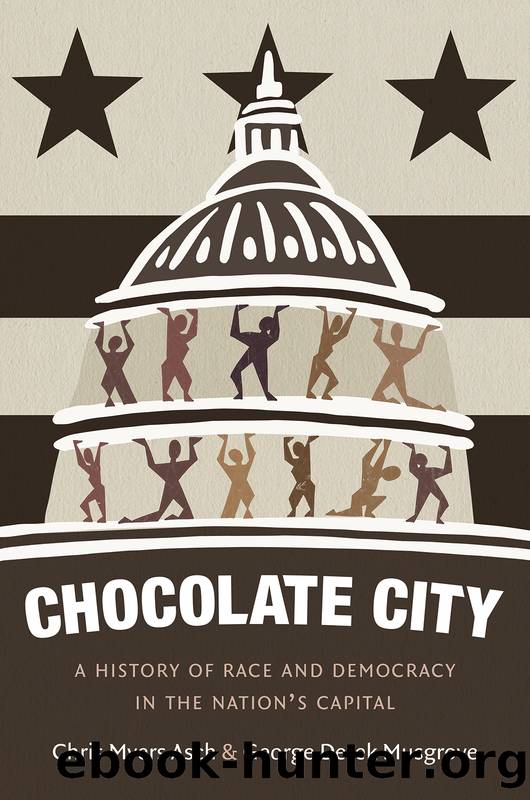

Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation's Capital by Chris Myers Asch & George Derek Musgrove

Author:Chris Myers Asch & George Derek Musgrove [Asch, Chris Myers & Musgrove, George Derek]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 1469635860

Google: C2Y6DwAAQBAJ

Amazon: 1469635860

Goodreads: 34546713

Publisher: UNC Press Books

Published: 2017-10-16T23:00:00+00:00

ELEVEN

How Long? How Long?

Mounting Frustration within the Black Majority, 1956â1968

Direct action has called attention to problems and gotten token changes but it has made no real basic changes. Political and economic force will bring about permanent change.

âJULIUS HOBSON, 1964

Southwest is Washingtonâs âstepchild area,â wrote urban critic Jane Jacobs in 1956, a place âblackballed by geographyâ and âbuffeted by official whims.â The smallest of Washingtonâs quadrants in both size and population, Southwest does not feature distinct neighborhoods with historic names that reach back into the cityâs past; the entire area is known simply as âSouthwest.â Dubbed âthe Islandâ in the mid-nineteenth century, it historically has been isolated physically and culturally from the rest of the city, separated first by the infamous City Canal, then by a set of unsightly railroad tracks, and now by a confusing network of highways and exit ramps. These concrete ribbons slice Southwest into several pieces and render it relatively inaccessible to outsiders. Though tourists and many Washingtonians overlook Southwest, its history is central to the racial turmoil and activism that marked the city in the 1950s and 1960s.1

The Southwest we see in the early twenty-first century did not develop organically through two centuries of urban growth. Instead, it emerged suddenly in the decades after World War II. In the late 1940s, city officials, urban planners, and their allies in the local press and business community grew increasingly worried about âthe flight to the suburbs.â The loss of city residents, wrote the Postâs Chalmers Roberts in a 1952 series ominously titled âProgress or Decay?,â was âthe central civic problem in Washington today.â City leaders feared that inner city âblightââa term borrowed from agriculture to depict a seemingly natural process of disease and decayâwas âinfectingâ the older neighborhoods in downtown Washington, including Southwest.2

At midcentury, Southwest was home to twenty-three thousand residents, more than 70 percent of whom were black and about 90 percent of whom were poor. âInside bathrooms, kitchen sinks, central heating and electric lights are luxuries of extreme rarity,â noted a 1942 survey; a decade later, another study found that 80 percent of the housing units were substandard. Journalists and photographers regularly juxtaposed ramshackle homes and plywood privies with the majestic Capitol and elegant federal buildings located just blocks away. But Southwest also featured fine row houses of brick or wood with carefully tended front and back lawns. Indeed, the Homebuildersâ Association of Metropolitan Washington found that many homes were âas sound and in many cases as large as fashionable homes in Georgetown.â3

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16623)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11489)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(7788)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(5771)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5036)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4824)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(4789)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4447)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(4417)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(4415)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4398)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4342)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4076)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4032)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4012)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(3881)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(3872)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3782)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3730)