Capital's Terrorists by Chad E. Pearson

Author:Chad E. Pearson

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

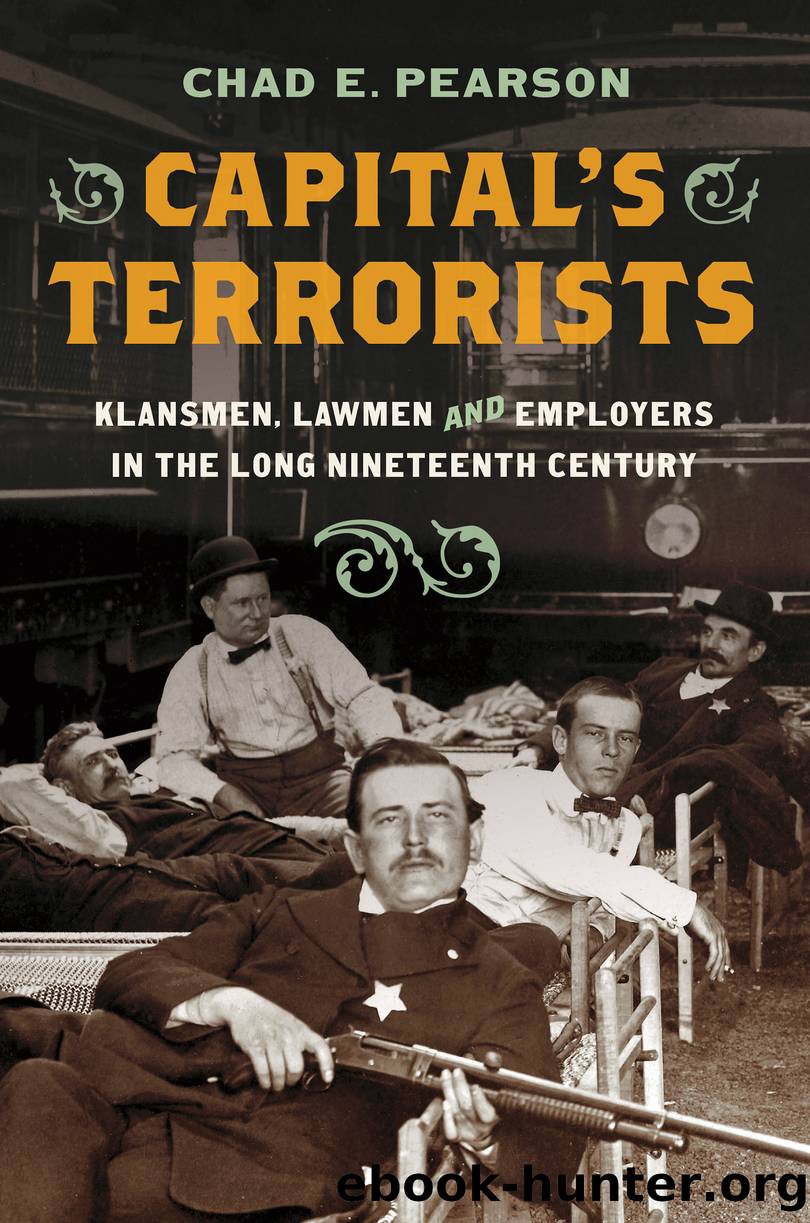

St. Louis posse members. The âBusinessmen of Responsibilityâ taking a break from terrorizing streetcar protestors. (George Stark Collection, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, Identifier: NO 1213)

Organization leaders remained uncompromising, and nothing distressed them more than laborâs sustained demands for closed shops. Ittner made this clear in 1906. The closed shop, in his view, âis without exception the worst curse that ever befell this country.â It was worse, he declared, than âwars, pestilence, cyclones, floods, earthquakes, fires, and all the other ills that humanity is heir to.â Ittnerâs hyperbolic comments suggests that he wanted readers to believe that the cityâs citizens, irrespective of their class positions, had a common enemy: dangerous unionists who demanded exclusive bargaining rights, which threatened to inflict on society a catastrophic and almost unlivable future. Such demands, which Ittner characterized as âvenomous and relentless,â had an adverse impact on not only employers, but also on job seekers uninterested in joining unions and on harmony-seeking community members. Ittnerâwho helped weaken the power of trade unions by overseeing the establishment of employer-controlled apprenticeship training programsâextended an olive branch to rank-and-filers, inviting them to reject unionism and âcome together in this city for the good of the city and State, and declare for the âopen shopâ.â95

St. Louisâs Citizensâ Industrial Association members, like those in northeastern Pennsylvania and Colorado, had much to learn from old-timers like Ittner, Thompson, and Goodwin. Members frequently met in the cityâs Odd Fellows building, a safe space for terrorists. Here they discussed ways to halt organized laborâs coercive and âunlawfulâ practices, and like others, they pledged themselves to secrecy. For example, to protect the organizationâs privacy during a November 1903 meeting, two security guards were stationed outside the meeting room where they prevented those without invitations from entering. That eveningâs highlight was a speech by Goodwin, whom a St. Louis paper exaggeratedly called âthe father of the movement.â For many attendees, the event must have ignited feelings of déjà vu, since they had followed the same social codes here, including adopting hyper-secret practices, that they had embraced close to two decades earlier.96

Hoping to earn respect from liberal-minded observersâfrom those both in and outside of industrial relations conflictsâSt. Louisâs union-battlers placed their movement in the broader context of American reform pursuits. An Exponent article made this point explicitly, noting that support for the open-shop principle included renowned figures from outside of industrial relations settings. The Citizensâ Industrial Association of St. Louis members proclaimed their support for the same labor relations system ardently championed by President Roosevelt and prominent reformers: âThe many utterances of the President of the United States, of the Anthracite Coal Commission, of university presidents such as Chas. W. Eliot of Harvard, are so many forceful expressions of our principles.â97 Clearly, powerful enablers and authoritative narrative-creators provided these frontline union-fighters with greater confidence and a renewed sense of legitimacy.

For his part, Goodwin helped to bring St. Louis members together with others throughout the state. In 1906, he joined with luminaries from Kansas City, St. Louis, Joplin, and Springfield to form The Federated Associations of Missouri.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16674)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11495)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(7806)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(5802)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5050)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4839)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(4796)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4459)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(4438)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(4426)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4423)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4353)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4089)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4043)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4026)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(3899)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(3881)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3791)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3742)