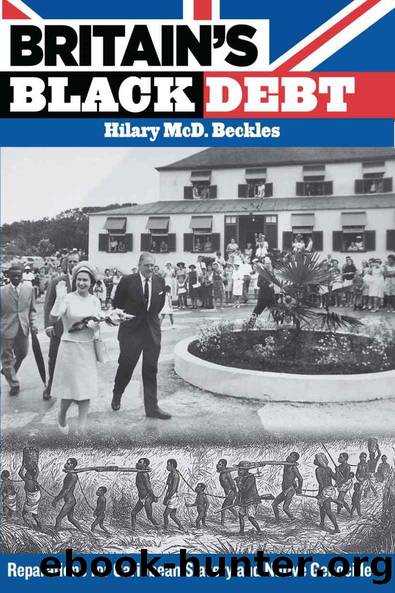

Britain's Black Debt: Reparations for Caribbean Slavery and Native Genocide by Beckles Hilary McD

Author:Beckles, Hilary McD [Beckles, Hilary McD]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of the West Indies Press

Published: 2012-12-31T21:00:00+00:00

Chapter 11

Twenty Million Pounds:

Slave Ownersâ Reparations

Many of the slave plantation owners in the West Indies had a direct link to Bristol and contributed much to the cityâs wealth. Ironically, the compensation that they received once full emancipation took effect in 1838 contributed further to the cityâs prosperity.

âStephen Williams, Member of Parliament, Debate on the Bicentenary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade, House of Commons, 20 March 2007

In 1838, the British people ended their 250-year-old ânational crimeâ of black enslavement with a sum total payment of £20 million to the last slave-owning cohort. From the perspective of the state, the cash payout represented an apology for aborting the property rights of citizens, a legal action that prompted a settlement as monetary reparations.1

Slavery, then, came to an end with a festive orgy of public money being showered upon slave owners, who for generations had been financially enriched, socially elevated and celebrated, and politically empowered and protected. Their final pillage came in the form of massive financial reparations from the British treasury. The £20 million were the last grains from the slave- endowed public granary.2

When the issue was discussed in Parliament, some politicians argued that the £20 million paid to slave owners was in fact back pay, part of the taxes the state had extracted with fiscal policies from the slave system. Others spoke of pay-up time from the British public that had enjoyed a higher standard of living as a result of cheap slave-produced products. They all recognized that British citizens were socially empowered by the white supremacy culture so effectively institutionalized on a global scale by slave owners. Underlying most statements made in Parliament, however, was an acceptance of the idea that the payment was in part compensation for the role slave owners had played in building the British Empire as a project that successfully enhanced national economic development.

Some ministers of government suggested that the reparation payment to slave owners was a political victory for all sides. Slave owners cashed in their chattel certificates (documents of ownership of black slaves) to the government and collected £20 million; on top of that, they retained access to those same freed Africans by being able to employ them as cheap labour. Blacks were doubly victimized. They got nothing by way of cash reparations to carry them into freedom. No land grants were provided. No promissory notes were posted. Slave owners ran to the banks. Although unchained, the enslaved remained captives of a constitution that rendered them disenfranchised labourers.

Draper has suggested new ways to look at todayâs value of the £20 million reparations that slave owners received in 1838. âThe British state of the 1830s was much smaller than it is today, and at 40 per cent of government receipts or expenditures, £20 million was a huge amount: it would equate to almost £200 billion today. . . . Finally, in relation to the size of the economy, the £20 million compensation would be the equivalent of around £76 billion.â3 The state and its

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7692)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5431)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5408)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4565)

The Sports Rules Book by Human Kinetics(4379)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(4375)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4242)

Captivate by Vanessa Van Edwards(3838)

Mummy Knew by Lisa James(3686)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3537)

The Worm at the Core by Sheldon Solomon(3486)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3460)

The 48 laws of power by Robert Greene & Joost Elffers(3247)

Suicide: A Study in Sociology by Emile Durkheim(3018)

The Slow Fix: Solve Problems, Work Smarter, and Live Better In a World Addicted to Speed by Carl Honore(3007)

The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell(2914)

Humans of New York by Brandon Stanton(2868)

Handbook of Forensic Sociology and Psychology by Stephen J. Morewitz & Mark L. Goldstein(2699)

The Happy Hooker by Xaviera Hollander(2686)