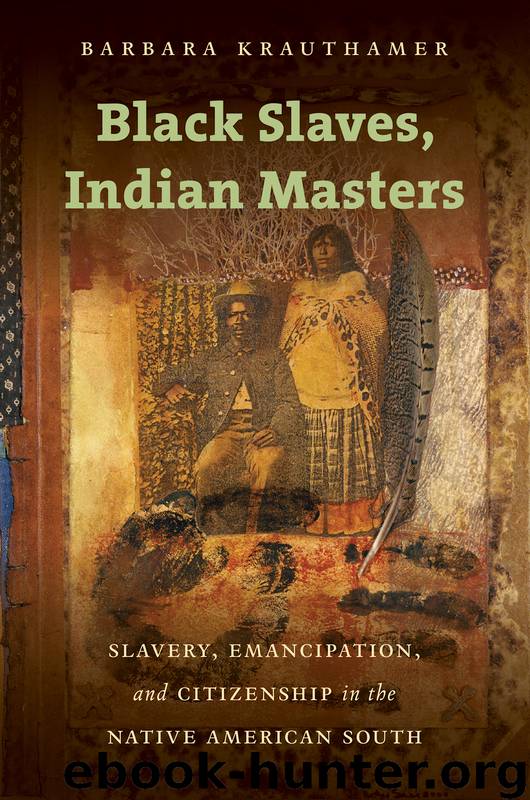

Black Slaves, Indian Masters by Barbara Krauthamer

Author:Barbara Krauthamer

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2013-08-02T16:00:00+00:00

5

Freedmen’s Political Organizing and the Ongoing Struggles over Citizenship, Sovereignty, and Squatters

Though emancipation came late in the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations, black people received the news of their liberation with joyous relief. The elderly Kiziah Love, a Choctaw freedwoman, recalled that when she learned of her freedom, she clapped her hands and thanked God that she was “free at last!” But the thrill of liberation was tainted with a heavy dose of uncertainty and apprehension.

From 1866 to 1868, black people waited to learn whether they would be granted citizenship in the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations or the United States under the terms of the 1866 treaty. Neither party adhered to the treaty’s provisions and June 1868 deadline, leaving an estimated 5,000 former slaves and their descendants with no certain standing in either the Indian nations or the United States.1 From 1868 through the end of the nineteenth century, the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and U.S. governments continually disputed and sidelined the issue of freedpeople’s citizenship.

Governmental inaction, however, did not dissuade freedpeople from organizing their lives in accordance with their own understandings and expectations of freedom. In the months and years following the 1866 treaty’s ratification, black men and women in the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations strove to make their freedom meaningful on a number of counts. Black men and women defined their freedom largely in terms of family, labor, land, and political participation. Matters of family, labor, and land were often intertwined, as people made decisions about where and with whom they would live and work. In some instances, families allied with each other, working collectively as sharecroppers, while other families fractured and set out in different directions. For many former slaves, freedom entailed claiming one of the fundamental rights traditionally associated with Choctaw or Chickasaw citizenship: using and improving unclaimed land to build their own homes and farms.

Black people’s understandings of their freedom revolved around the ongoing and unresolved questions of their citizenship. Black people, especially men, insisted upon presenting their views and voicing their opinions in the public conversations about the 1866 treaty provisions regarding freedpeople’s citizenship. When black men faced Indian leaders and U.S. authorities, they presented their own interpretations of the treaty’s provisions, often taking both parties to task for failing to abide by the letter and spirit of the treaty. Black men’s political participation in this context is especially noteworthy because of the ways they addressed the issues of race, land, and sovereignty that lay at the core of not only the 1866 treaty but also U.S. Indian policy and Choctaw and Chickasaw responses to American domination.

In the early months of freedom, black people found little to give them hope in the new order. The period between the Fort Smith council in September 1865 and the ratification of the Choctaw/Chickasaw treaty in April 1866 was an exhilarating but tumultuous time for the thousands of black people freed from slavery. Recalcitrant slaveholders, Indian and white vigilantes, and intractable lawmakers sought almost any opportunity that arose to keep black people as close to enslavement as possible.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| General | Discrimination & Racism |

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(6629)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(4695)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4338)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(3663)

The Sports Rules Book by Human Kinetics(3582)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(3576)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(3494)

Captivate by Vanessa Van Edwards(3292)

Mummy Knew by Lisa James(3164)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(2941)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(2922)

The Worm at the Core by Sheldon Solomon(2910)

Suicide: A Study in Sociology by Emile Durkheim(2606)

The Slow Fix: Solve Problems, Work Smarter, and Live Better In a World Addicted to Speed by Carl Honore(2570)

Humans of New York by Brandon Stanton(2376)

Handbook of Forensic Sociology and Psychology by Stephen J. Morewitz & Mark L. Goldstein(2376)

Blackwell Companion to Sociology, The by Judith R. Blau(2315)

The Happy Hooker by Xaviera Hollander(2272)

Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell(2254)