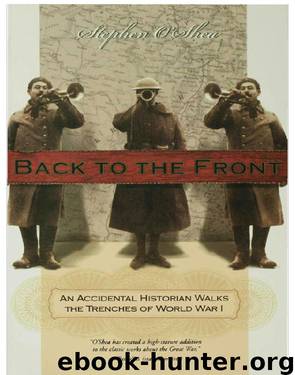

Back to the Front by Stephen O'Shea

Author:Stephen O'Shea

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Published: 2009-09-27T16:00:00+00:00

4. The Noyon Salient

The Noyon Salient was a large bulge in the German lines, a blunted belly of destruction and menace that hung over Paris, some sixty miles to the south. The Front, as one walks down it from Flanders and Artois, turns left in this part of Picardy and heads east toward Champagne. Noyon, as befits a turning point, has the distinction of being a palindrome. Sex at Noyon taxes.

The word play is not mere whimsy—Noyon is also the birthplace of John Calvin, the man whose followers would make income a metaphysical come-on. And Calvin's unexpected appearance in Noyon, in turn, coincides nicely with Ypres's relation to Cornelius Jansen. Oddly, two great Christian reformers are associated with the two great salients of the Western Front, two catalysts of religious renewal connected to two catalysts of deicidal disbelief. It's as if St. Francis came from Antietam, twice.

All of the towns and villages within an immediate southerly radius of Noyon were deliberately destroyed in the spring of 1917, when the Germans evacuated the bulge and fell back on the Siegfriedstellung, or Hindenburg Line, a fortified defensive position that allowed them to shorten their trenches. The Germans laid waste to hundreds of square miles of land when they made their surprise withdrawal from the salient around Noyon. It was one of the greatest property crimes ever perpetrated on France—farmland was ravaged, towns dynamited, wells poisoned, churches and castles destroyed, and the resulting rubble booby-trapped. Until then, the Noyon Salient had been a relatively quiet sector of the Front. But quiet—especially "all quiet" — is a loaded term. In those times when no great offensives were being held, it is estimated that the French army alone lost 100,000 men a month. For end-of-the-century ears, the number sounds impossibly, unimaginably large.

My walk through this part of Picardy inspires little more than a few consecutive days of irritation. A province of France rich in cathedrals and supposedly redolent of medieval glory, Picardy south of the Santerre reveals itself to be a blanket of rural bleakness made even more disagreeable to the walker by impassable thruways and fenced-off train lines. The express from Paris to the northern city of Valenciennes once derailed in this washed-out Pissarro landscape because of a sudden track subsidence. The railbed, at the point where it crossed the Front, collapsed into an unseen and unsuspected underground hollow made by an old trench. For once history had undermined engineering, rather than the other way around.

I look at my route map. Fouquescourt, Damery, Beauvraignes, Crapeaumesnil. Lackadaisical little villages file by in the shuttered-up silence of midafternoon, their only structure of note the inevitable and usually dramatic war memorial. A maiden weeps, a soldier falls, a cock crows—all decisions made by town councilors when a postwar French government decreed the erection of a monument to the war dead a legal obligation. The eternal duet of small-town France—mairie vs. church—was joined by a mute third party, so that even the most insignificant collection of houses now has a memorial in its midst.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12003)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4901)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4762)

The Templars by Dan Jones(4672)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4475)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4190)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(3987)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3942)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3935)

12 Strong by Doug Stanton(3539)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3321)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3181)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(3162)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3112)

The Art of War Visualized by Jessica Hagy(2988)

Hitler's Flying Saucers: A Guide to German Flying Discs of the Second World War by Stevens Henry(2742)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2661)

The Second World Wars by Victor Davis Hanson(2514)

Tobruk by Peter Fitzsimons(2496)