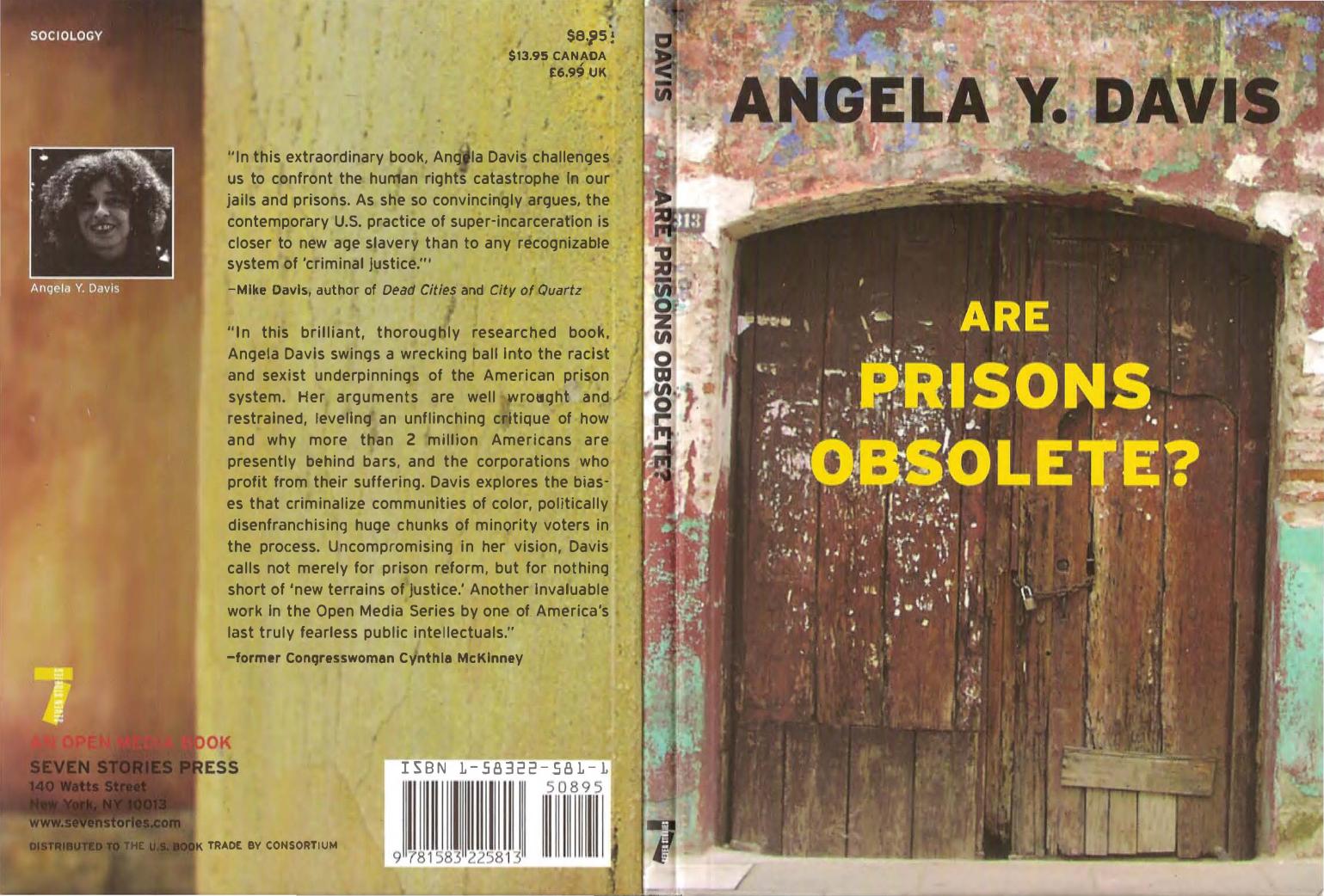

Are Prisons Obsolete? by Angela Y. Davis

Author:Angela Y. Davis [Angela Y. Davis]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

ISBN: 9781609801045

Publisher: Seven Stories Press

Published: 2010-07-29T04:00:00+00:00

Male punishment was linked ideologically to penitence and reform. The very forfeiture of rights and liberties implied that with self-reflection, religious study, and work, male convicts could achieve redemption and could recover these rights and liberties. However, since women were not acknowledged as securely in possession of these rights, they were not eligible to participate in this process of redemption.

According to dominant views, women convicts were irrevocably fallen women, with no possibility of salvation. If male criminals were considered to be public individuals who had simply violated the social contract, female criminals were seen as having transgressed fundamental moral principles of womanhood. The reformers, who, following Elizabeth Fry, argued that women were capable of redemption, did not really contest these ideological assumptions about women’s place. In other words, they did not question the very notion of “fallen women.” Rather, they simply opposed the idea that “fallen women” could not be saved. They could be saved, the reformers contended, and toward that end they advocated separate penal facilities and a specifically female approach to punishment. Their approach called for architectural models that replaced cells with cottages and “rooms” in a way that was supposed to infuse domesticity into prison life. This model facilitated a regime devised to reintegrate criminalized women into the domestic life of wife and mother. They did not, however, acknowledge the class and race underpinnings of this regime. Training that was, on the surface, designed to produce good wives and mothers in effect steered poor women (and especially black women) into “free world” jobs in domestic service. Instead of stay-at-home skilled wives and mothers, many women prisoners, upon release, would become maids, cooks, and washerwomen for more affluent women. A female custodial staff, the reformers also argued, would minimize the sexual temptations, which they believed were often at the root of female criminality.

When the reform movement calling for separate prisons for women emerged in England and the United States during the nineteenth century, Elizabeth Fry, Josephine Shaw, and other advocates argued against the established idea that criminal women were beyond the reach of moral rehabilitation. Like male convicts, who presumably could be “corrected” by rigorous prison regimes, female convicts, they suggested, could also be molded into moral beings by differently gendered imprisonment regimes. Architectural changes, domestic regimes, and an all-female custodial staff were implemented in the reformatory program proposed by reformers,82 and eventually women’s prisons became as strongly anchored to the social landscape as men’s prisons, but even more invisible. Their greater invisibility was as much a reflection of the way women’s domestic duties under patriarchy were assumed to be normal, natural, and consequently invisible as it was of the relatively small numbers of women incarcerated in these new institutions.

Twenty-one years after the first English reformatory for women was established in London in 1853, the first U.S. reformatory for women was opened in Indiana. The aim was totrain the prisoners in the “important” female role of domesticity. Thus an important role of the reform movement in women’s prisons

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19010)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12179)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8878)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6866)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6253)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5776)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5722)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5487)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5418)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5207)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5135)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5070)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4942)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4904)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4766)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4733)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4691)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4494)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4477)