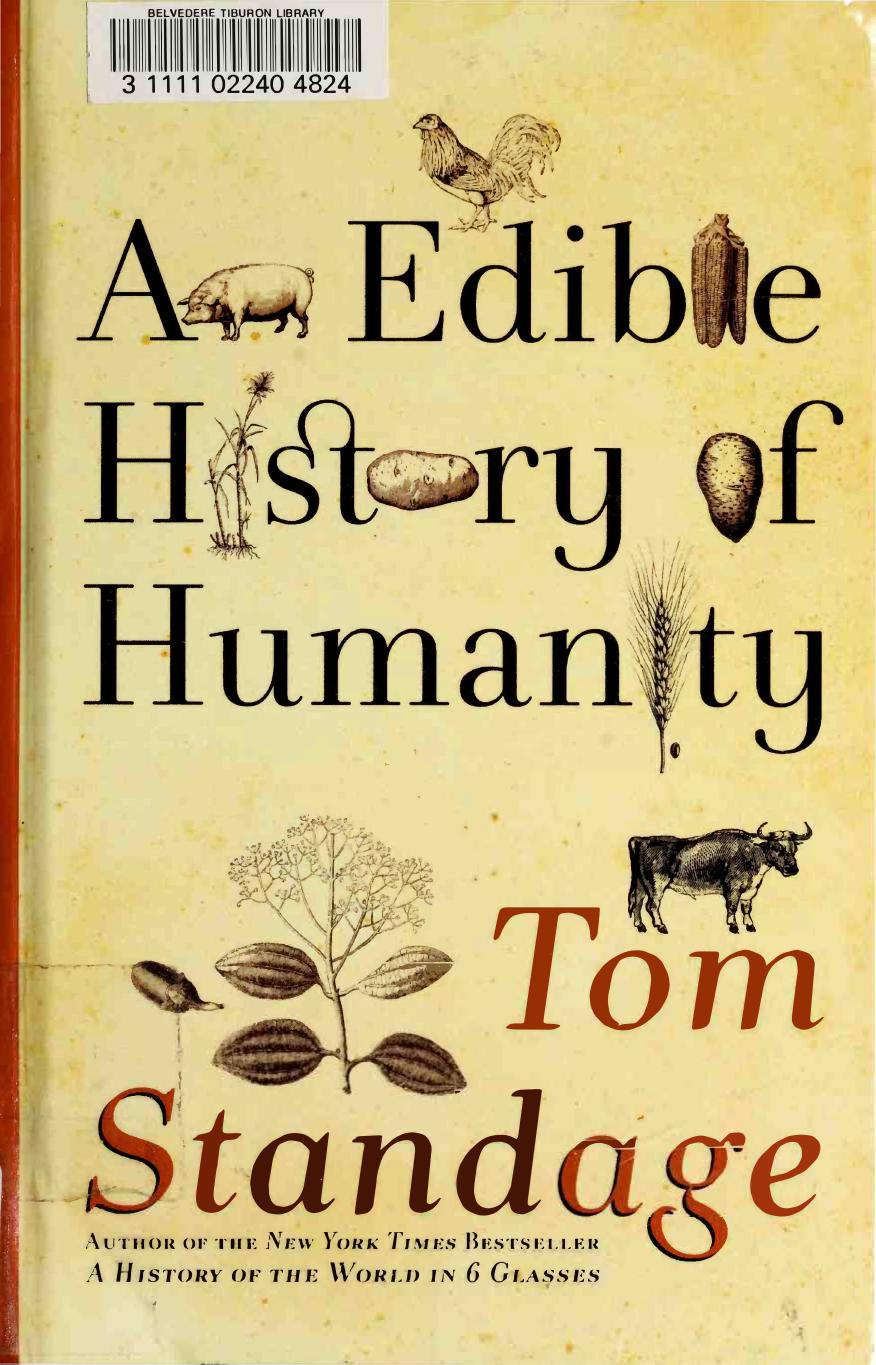

An Edible History of Humanity by Tom Standage

Author:Tom Standage

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub, pdf

Tags: History

ISBN: 9780802719911

Publisher: Walker & Company

Published: 2008-01-02T00:00:00+00:00

THE FUELS OF INDUSTRY

The shift to using coal rather than wood as a fuel was a second trend that contributed to Britain’s industrialization. People much preferred burning wood rather than coal in their homes, but as land became more sought after for agricultural use, areas that had previously provided firewood were cleared to make way for farming. The price of firewood shot up—it increased threefold in western European cities between 1700 and 1800—and people turned to coal as a cheaper fuel. (It was cheap in England, at least, since there were plentiful deposits near the surface.) One ton of coal provides the same amount of heat as the wood that can be sustainably harvested each year from one acre of land. In England and Wales, some seven million acres of land that had previously provided wood, or around one fifth of the total surface area, were taken under cultivation between 1700 and 1800. This ensured that the growth of the food supply could continue to keep pace with the population—but required everybody to switch to burning coal.

And switch they did: The actual consumption of coal by 1800 was about ten million tons a year, providing as much energy as would otherwise have required ten million acres to be set aside for fuel production. At this point Britain accounted for 90 percent of world coal output, by some estimates. When it came to fuel, at least, Britain had already escaped from the constraints of the biological old regime. Rather than relying on living plants to trap sunlight to produce fuel, coal provided a way to tap vast reserves of past sunlight, accumulated millions of years ago and stored underground in the form of dead plants.

Although it was originally exploited as an alternative to wood for domestic heating, the abundance of coal meant that it was soon being put to other uses. Arthur Young, an English agricultural writer and social observer, was struck by the relative scarcity of glass in windows while traveling in France in the 1780s; it was far more widespread in England by this time because coal provided cheap energy for glass-making. (French glassmakers, meanwhile, were so desperate for fuel that they had resorted to burning olive pits.) Coal was also heavily used by the textile industry, to warm the liquids used in bleaching, dyeing, and printing and to heat drying rooms and presses. Coal enabled a rapid expansion in the production of iron and steel, which had previously been smelted using wood. And, of course, coal was used to power steam engines, a technology that emerged from the coal industry itself.

Once England’s outcropping surface deposits of coal had been depleted, it was necessary to sink mine shafts, and to ever greater depths—but the deeper they went, the more likely they were to flood with water. The steam engine invented by Thomas Newcomen in 1712, building on the work of previous experimenters, was built specifically to pump water out of flooded mines. Early steam engines were very inefficient, but

Download

An Edible History of Humanity by Tom Standage.epub

An Edible History of Humanity by Tom Standage.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Craft Beer for the Homebrewer by Michael Agnew(17461)

Marijuana Grower's Handbook by Ed Rosenthal(3122)

Barkskins by Annie Proulx(2884)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(2667)

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine by Anne Applebaum(2467)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2458)

Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation by Tradd Cotter(2313)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2228)

In the Woods by Tana French(2005)

Beer is proof God loves us by Charles W. Bamforth(1935)

The Art of Making Gelato by Morgan Morano(1901)

Meathooked by Marta Zaraska(1893)

Birds, Beasts and Relatives by Gerald Durrell(1869)

Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor(1856)

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change (25th Anniversary Edition) by Covey Stephen R(1839)

Borders by unknow(1790)

The Lean Farm Guide to Growing Vegetables: More In-Depth Lean Techniques for Efficient Organic Production by Ben Hartman(1789)

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change by Stephen R. Covey(1767)

Urban Farming by Thomas Fox(1751)