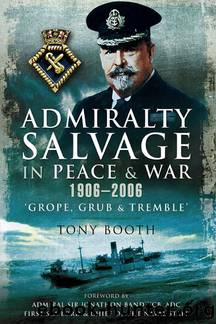

Admiralty Salvage in Peace and War 1906â2006 by Tony Booth

Author:Tony Booth [Booth, Tony]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, Military, Naval

ISBN: 9781781596272

Google: y9awBAAAQBAJ

Publisher: Pen and Sword

Published: 2007-10-06T03:18:08+00:00

Any person acting on behalf of His Majesty may take such steps and use such force as may appear to that person to be reasonably necessary for securing compliance with any direction given under this Regulation or, where an offence against the Regulation has been committed by reason of failure to comply with any such direction, for enabling proceedings in respect of the offence to be effectually taken.

However, overcoming the British legal system still proved to be rather easier than gaining the full co-operation of the commercial salvage companies.

The Admiralty had to alter many of the contracts to suit each companyâs demands, meaning that some were able to negotiate better deals than others. The Port of London Authority, for instance, refused to agree to no salvage award and managed to cut a deal whereby the firm split awards with the Admiralty. No other salvage firm managed this. Southampton-based Risdon Beazely were paid £20,000 for the services of three salvage officers and two vessels. The Liverpool & Glasgow Salvage Association had also signed the same agreement. Metal Industries were the only firm who flatly refused to sign. Their reluctance became so acute that it finally constituted an âinterference with the war effortâ. But this was not without justification.

Each agreement specified that key salvage personnel were to be seconded to the Admiralty and, although being given Royal Naval Reserve commissions, they were formally known as Civil Salvage Officers. They were to be paid between £750 and £1,500 per annum, depending on experience, at a time when the average yearly wage for a shore-based engineer was about £360. The Admiralty wanted three men from Metal Industries to sign the agreement: 50-year-old Thomas McKenzie, 29-year-old Harry Murray Taylor and 37-year-old James Robertson. They had all learnt the salvage business working for Cox & Danks raising the scuttled German fleet in Scapa Flow prior to continuing their work for Metal Industries, and were all highly skilled men.

On 23 December 1941, the Admiralty wrote to McKenzie, Murray Taylor and Robertson informing them that Metal Industries had sanctioned their appointments to the Salvage Department. Through some miscommunication Metal Industriesâ approval had never been sought, or at least the three men had no knowledge until they opened the official envelopes and fully digested their contents. All three were outraged at their alleged sudden transfer to government control without any discussion, and they made their grievances known, both to their employers and to the Admiralty. After what must have been a very troubled Christmas, McKenzie wrote to the Admiralty saying: âMy directors assure me that they have never at any time suggested to my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty that the terms offered in your letter would be accepted, and I have on a number of occasions informed the Director of Salvage personally that I would not accept the terms suggested.â

Murray Taylor was even more cutting when he wrote quite bluntly: âI am surprised to learn that the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty understand that I will become a

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Drafting & Mechanical Drawing | Fluid Dynamics |

| Fracture Mechanics | Hydraulics |

| Machinery | Robotics & Automation |

| Tribology | Welding |

Whiskies Galore by Ian Buxton(41992)

Introduction to Aircraft Design (Cambridge Aerospace Series) by John P. Fielding(33115)

Small Unmanned Fixed-wing Aircraft Design by Andrew J. Keane Andras Sobester James P. Scanlan & András Sóbester & James P. Scanlan(32788)

Craft Beer for the Homebrewer by Michael Agnew(18235)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(8040)

The Complete Stick Figure Physics Tutorials by Allen Sarah(7362)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(6930)

Kaplan MCAT General Chemistry Review by Kaplan(6926)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6610)

Modelling of Convective Heat and Mass Transfer in Rotating Flows by Igor V. Shevchuk(6432)

Learning SQL by Alan Beaulieu(6278)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6264)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(6002)

Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport;(5748)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5545)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5408)

Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion: Tesla, UFOs, and Classified Aerospace Technology by Ph.D. Paul A. Laviolette(5364)

Design of Trajectory Optimization Approach for Space Maneuver Vehicle Skip Entry Problems by Runqi Chai & Al Savvaris & Antonios Tsourdos & Senchun Chai(5063)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4996)