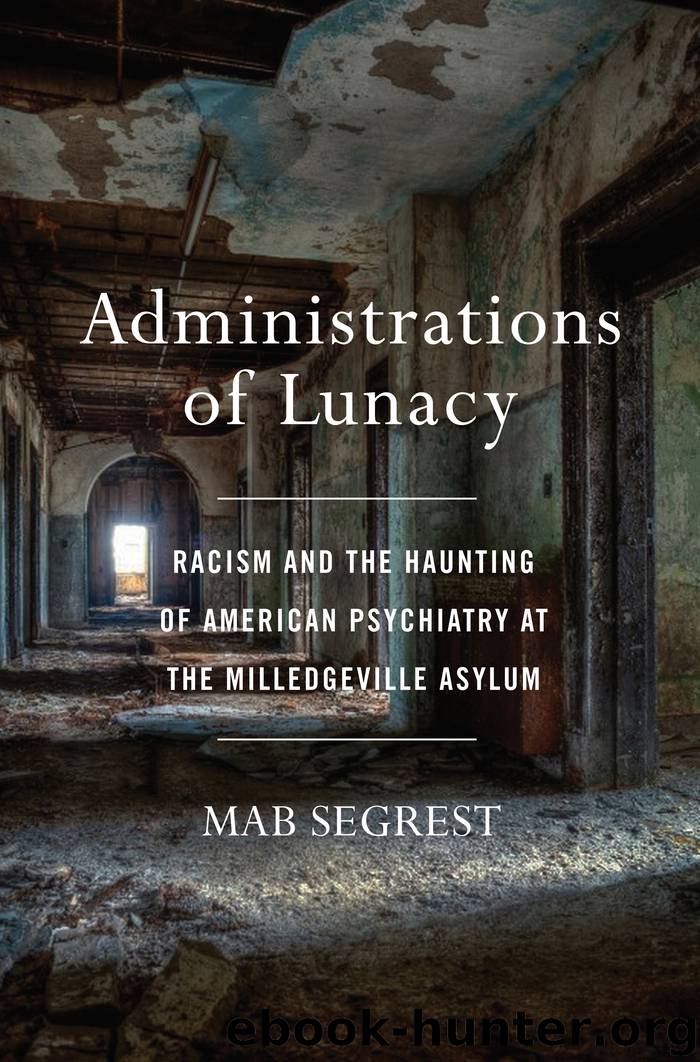

Administrations of Lunacy by Mab Segrest

Author:Mab Segrest

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The New Press

Published: 2020-06-14T16:00:00+00:00

13

Plantation—Asylum—Prison

The habitual criminal is the product of pathological and atavistic anomalies; he stands midway between the lunatic and the savage.

—W. Douglas Marrison, quoted in T.O Powell1

In 2010, when Central State Hospital closed its doors under federal court order, what had been at various times the largest state mental hospital in the United States—and at times in the world—was replaced at every level by a prison. Today, the Baldwin County Jail, the Fulton County Jail, and Chicago’s Cook County jail are the largest in their respective U.S. governing units (the county, the state, and the nation). These prisons and jails are the concrete, brick, and mortar equivalents of the twenty-five thousand bodies stretching into the Baldwin County woods as far as the eye can see—or the bodies that have had their bones brought up in the roots of trees, so the stories go, in a monster storm. These living and dead bodies in the ground or behind bars are not coincidences, but old patterns of harm unbroken across the centuries—and such patterns, or “afterlives,” are what eventually constitutes the haunting of psychiatry in this book’s title. Here at the century’s turn, the Georgia Asylum-cum-Sanitarium is slipping its Enlightenment moorings and (re)turning to the Gothic, the grotesque, the repressed. As the brilliant southern literary critic Patsy Yeager described a century later: “Trauma has been absorbed into the landscape … of repudiated, throwaway bodies that mire the earth: a landscape built over and upon the melancholic detritus.”2

So, in the late nineteenth century, the insanity plea I suspect that patient Osborne copped was not the only issue that linked the asylum-sanitarium to Georgia’s expanding penal system. By the turn of the twentieth century, the plantation was their primary intermediary. The rising numbers of African Americans in the convict lease system and in the asylum in the 1870s and 1880s offered their own synchronicity, their less than coincidence that starts to feel uncanny. Baldwin County’s dethroned status as state capital made it handy for the state when it wanted to use or acquire state-owned land for other types of confinement, which Georgia did in 1897 with the State Prison Farm. By the late 1880s, the asylum’s population makeup, with its 30 percent African American patients, coincided with an increase in the Georgia Asylum’s agricultural production—measured precisely in pounds, bushels, quarters, and dozens. These things together pointed to a social geography becoming less “morally therapeutic” and more like a plantation whose various tasks offered its involuntarily committed patients “occupational therapy,” since little other therapy was available.

Like distributions of goods, patients’ work was also structured by raced and gendered political economies. In 1893, the steward J.L. Lamar reported the results of the year’s labors across a “variety of departments … [that] have given employment to quite a large number of patients of both sexes.” The matron’s report that year reflected “a large amount and variety of work done by female patients, such as making, repairing, etc” with the “garden and dairy, grading and excavation” all giving “outdoor employment to many of the male patients.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| General | Discrimination & Racism |

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(6629)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(4692)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4336)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(3662)

The Sports Rules Book by Human Kinetics(3581)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(3575)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(3494)

Captivate by Vanessa Van Edwards(3292)

Mummy Knew by Lisa James(3163)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(2940)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(2919)

The Worm at the Core by Sheldon Solomon(2910)

Suicide: A Study in Sociology by Emile Durkheim(2605)

The Slow Fix: Solve Problems, Work Smarter, and Live Better In a World Addicted to Speed by Carl Honore(2570)

Humans of New York by Brandon Stanton(2376)

Handbook of Forensic Sociology and Psychology by Stephen J. Morewitz & Mark L. Goldstein(2376)

Blackwell Companion to Sociology, The by Judith R. Blau(2313)

The Happy Hooker by Xaviera Hollander(2271)

Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell(2254)