A. Philip Randolph by Andrew E. Kersten

Author:Andrew E. Kersten [Kersten, Andrew E.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780742569225

Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

Published: 2013-06-25T04:00:00+00:00

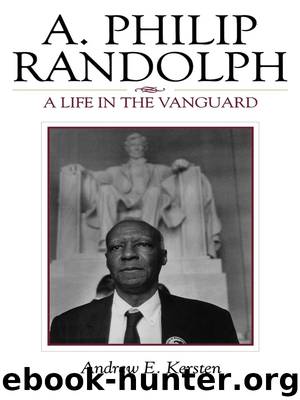

A. Philip Randolph (right) and Grant Reynolds (left) testify before the Senate Armed Serves Committee, 1948, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, NYWT&S Collection, LC-USZ62-128074.

Randolph always had collaborators: Chandler Owen in the 1910s and Milton Webster in the 1930s and 1940s. Rustin was, however, his most capable lieutenant. Born in 1910 in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Bayard had a normal childhood to a point. His neighborhood was rather affluent, and his family, which ran a successful catering business, rented an enormous house. Rustin excelled at school, often making the white kids jealous. He went to college at the City University of New York as Randolph had twenty years earlier. In Harlem, Rustin also joined the American Communist Party, which had a well-deserved reputation for supporting civil rights. In 1941, he split with the communists when the party’s Central Committee ordered him to stop agitating for civil rights. Communist Party officials feared that criticizing the United States’ record on race relations and pushing for reform might harm the war effort particularly because after Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union Stalin needed America’s help. Rustin and the communists parted ways, and it was at this moment that Rustin first met A. Philip Randolph. He had carefully avoided Randolph for years out of an antipathy for socialism. But now Randolph’s political faith seemed more reasonable than the communist one he had just disavowed. Although Randolph hated the communists, he looked past Rustin’s ideological commitment and gave him a post within his wartime March on Washington Movement. Randolph also introduced Rustin to a wider group of activists, including A. J. Muste, the head of the pacifist and civil rights-focused Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR).

Rustin’s work with FOR and its civil rights offshoot, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), was cut short in 1943. A Quaker, Rustin had invoked his religious right to avoid military combat service, which by World War II was possible. However, Rustin also refused to accept any alternative service, such as hospital work, that would have benefited the American war effort. The unsympathetic federal government sent him to prison at Lewisburg Penitentiary for four years. In 1947, Rustin reconnected with CORE and the growing civil rights movement. Sensing that their moment for significant reform was near, activists pushed hard on many fronts. Rustin was a key player. In addition to the efforts to desegregate the military, he collaborated with CORE to integrate public facilities in the South. In 1947, he joined a CORE group that tested the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Irene Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia (1946), which had declared segregation on interstate buses unconstitutional. CORE’s 1947 “Journey of Reconciliation” involved an interracial group of civil rights workers riding in buses through southern states. In April 1947, Rustin and fifteen other white and black activists boarded Trailways buses in various southern cities and refused to sit according to custom: whites in the front and blacks in the back. Rustin and the other freedom riders were arrested. They immediately called the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19002)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12177)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8874)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6857)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6249)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5768)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5718)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5482)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5409)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5200)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5132)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5065)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4900)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4761)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4727)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4685)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4489)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4474)