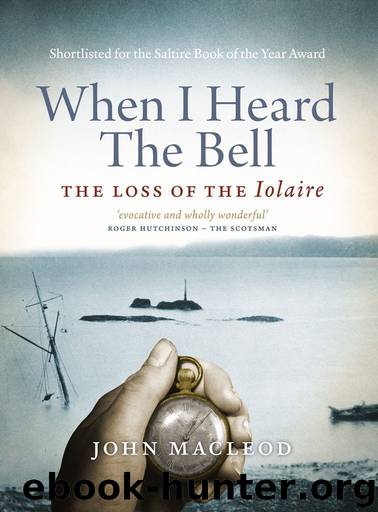

When I Heard the Bell: The Loss of the Iolaire by John MacLeod

Author:John MacLeod [MacLeod, John]

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

ISBN: 9780857905116

Publisher: Birlinn

Published: 2012-12-10T05:00:00+00:00

The Iolaire had, of course, sailed from Stornoway on the 31st. The report of a ship requiring a pilot may have turned on misunderstanding of one word – a ‘blue light’ had been seen, but in 1919, as one or two statements in File 693 unconsciously attest, a rocket (and especially a non-explosive rocket) was often described as a ‘light’. A blue lantern, though, hung on the bridge, was the usual signal for a pilot; the blue rockets had been a cry for help. The misunderstanding was not Boyle’s, who got the report third-hand, but Ainsdale’s – it nevertheless lost precious time. Wenlock actually had located the wreck – though he could not approach – and it is most unlikely exhausted Iolaire survivors were in Boyle’s office as early as 3.30 a.m. We might note there is here no reference to the involvement of Wenlock or any other RNR officer in the retrieval of Donald Morrison.

On Thursday 2nd, Royal Naval divers from the Stornoway base, after laboriously donning the cumbersome kit of the day, descended to the wreck. Thomas George Gusterson, from Sussex, was stalked for the rest of his life by what he had seen – ‘I found myself among a sea of bodies’ – and flatly refused to go down again. Later that night, the Rear-Admiral could telegraph details of the wrecked hulk. ‘Divers report yacht Iolaire completely broken in two abaft foremast. After part completely wrecked except skin of ship. Divers think boiler blew up but this is not borne out by evidence of survivors and mainmast is still standing.’ This, too, is interesting. Any iron steamship will make loudest report when her back breaks; and with her furnaces still ablaze with coal one might well expect much flash and hiss in the instant of disintegration. The ‘explosion’ at foundering became a very early part of enduring Iolaire folklore and, even by the time of the Fatal Accident Inquiry, vivid press reports had evidently convinced some survivors they must have seen one.

Within twenty-four hours – at 12.30 p.m. on Saturday the 4th – there was a curt reply to the request for a court martial. It was refused. ‘Court of Enquiry is to be held.’ Boyle’s heart sank. A Court of Inquiry (to use the Scots spelling) required far more work; could be of broadest scope, focusing pitilessly on the chaos of rescue efforts from land; and might even implicate him. His mood cannot have improved when he received formal intimation that day from Archibald Munro, Town Clerk, of the Town Council resolution. It was forwarded to London and, on 18 January – less than candidly; Admiralty inquiries were by then complete – their Lordships were pleased to assure Stornoway Town Council that the ‘cause of the disaster will be fully investigated.’

Boyle busied himself with details, even telegraphing on the Sabbath with fussy reflections on the wreck at Holm. ‘Divers report is unreliable. By using waterglass at LWS [low water spring-tide] it appears that the sheer deck aft is intact.

Download

When I Heard the Bell: The Loss of the Iolaire by John MacLeod.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Automotive | Engineering |

| Transportation |

Small Unmanned Fixed-wing Aircraft Design by Andrew J. Keane Andras Sobester James P. Scanlan & András Sóbester & James P. Scanlan(32789)

Navigation and Map Reading by K Andrew(5150)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4769)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(2197)

The Box by Marc Levinson(1989)

Top 10 Prague (EYEWITNESS TOP 10 TRAVEL GUIDES) by DK(1985)

Wild Ride by Adam Lashinsky(1972)

The Race for Hitler's X-Planes: Britain's 1945 Mission to Capture Secret Luftwaffe Technology by John Christopher(1858)

The One Percenter Encyclopedia by Bill Hayes(1825)

Trans-Siberian Railway by Lonely Planet(1752)

Girls Auto Clinic Glove Box Guide by Patrice Banks(1724)

Bligh by Rob Mundle(1689)

Looking for a Ship by John McPhee(1674)

Good with Words by Patrick Barry(1655)

Batavia's Graveyard by Mike Dash(1650)

TWA 800 by Jack Cashill(1649)

Fighting Hitler's Jets: The Extraordinary Story of the American Airmen Who Beat the Luftwaffe and Defeated Nazi Germany by Robert F. Dorr(1622)

Troubleshooting and Repair of Diesel Engines by Paul Dempsey(1595)

Ticket to Ride by Tom Chesshyre(1586)