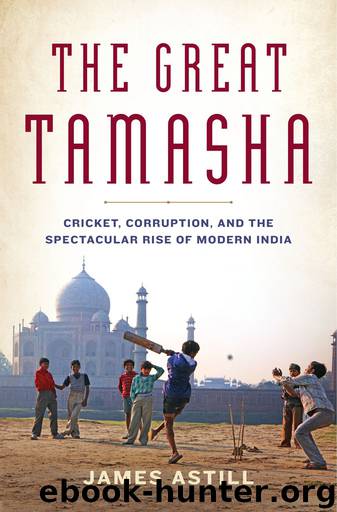

The Great Tamasha by James Astill

Author:James Astill [Astill, James]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

Published: 0101-01-01T00:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER SIX

Cricket, Caste and the Countryside

By 7am the sun was climbing over Dharavi, a big slum in Mumbai, and a symphony of clanging metal and whirring machinery resounding from its thousands of hut factories. The working day had begun. In cramped and murky spaces, poor slum-dwellers were labouring to produce shoes, clothes, toys and recycled materials, goods worth millions of dollars a year in exports alone. Dharavi, a square mile of low-rise wood, concrete and rusted iron, is one of the biggest slums in Asia. It is also, amid the poverty and filth, astonishingly industrious.

Chetan Jaiswal, a 26-year-old slumdog, had found better employment, working at a stockbrokers in the nearby district of Bandra. We had arranged to meet on a Monday morning, before he left the slum to spend his day ‘sitting in front of a computer screen, buying shares for people,’ and Chetan was anxious not to be late. He was waiting for me, motorbike helmet in hand, on a busy thoroughfare bordering the slum. Yet Chetan, who was reckoned to be the best cricketer in Dharavi, had time for a five-rupee cup of chai and a chat.

He had had a good weekend. The previous day Chetan had taken four for 14 for his company, Total Securities, playing on Azad Maidan. As we sat down on a roadside seat to drink our tea, he modestly accepted my congratulations. ‘I am very lucky,’ he said. ‘Because of cricket I can live, I can work, I can give money to my family. It means I have my bike, it means I can roam with my friends. Cricket is my life.’

Dharavi, which I had visited often during my time in India, was cricket-mad. The great majority of its million inhabitants, a multitude of poor migrants drawn to Mumbai from all over India, seemed to love the game. Yet there is no record of the slum having produced a single first-class cricketer, and it was easy to see why.

It has no sports facilities. To play games of tennis-ball cricket, Dhjaravi’s youngsters had only three nearby yards to choose from, including the Dharavi-Sion Sports Club, which I had visited the previous day. It was optimistically named. Half an hour’s walk from the slum, the club was merely half an acre of bare, gritty ground.

This made Chetan’s achievements all the more impressive. The son of a poor migrant from Uttar Pradesh, he had learned cricket playing in cramped alleys inside Dharavi. It had been obvious from early on that he had a talent. ‘I was always better than the others,’ he said with the same imposing self-confidence – the testosterone-whiff of a sportsman – that Arvind Pujara had radiated. So Chetan’s father, who worked as a porter in Mumbai’s port, sent him as a 15th-birthday present to the nearby Matunga Gymkhana. That gave Chetan his first experience of real cricket, played with a hard leather ball, and he found the adjustment hard. ‘I was terrified of the ball,’ he confessed. ‘I still am.’

Yet he visited

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5558)

The Sports Rules Book by Human Kinetics(4388)

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff(4293)

ACT Math For Dummies by Zegarelli Mark(4049)

Unlabel: Selling You Without Selling Out by Marc Ecko(3664)

Blood, Sweat, and Pixels by Jason Schreier(3625)

Hidden Persuasion: 33 psychological influence techniques in advertising by Marc Andrews & Matthijs van Leeuwen & Rick van Baaren(3566)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(3439)

Bad Pharma by Ben Goldacre(3428)

Urban Outlaw by Magnus Walker(3400)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(3221)

Kitchen confidential by Anthony Bourdain(3091)

Brotopia by Emily Chang(3056)

Slugfest by Reed Tucker(3005)

The Content Trap by Bharat Anand(2927)

The Airbnb Story by Leigh Gallagher(2857)

Coffee for One by KJ Fallon(2638)

Smuggler's Cove: Exotic Cocktails, Rum, and the Cult of Tiki by Martin Cate & Rebecca Cate(2541)

Beer is proof God loves us by Charles W. Bamforth(2464)